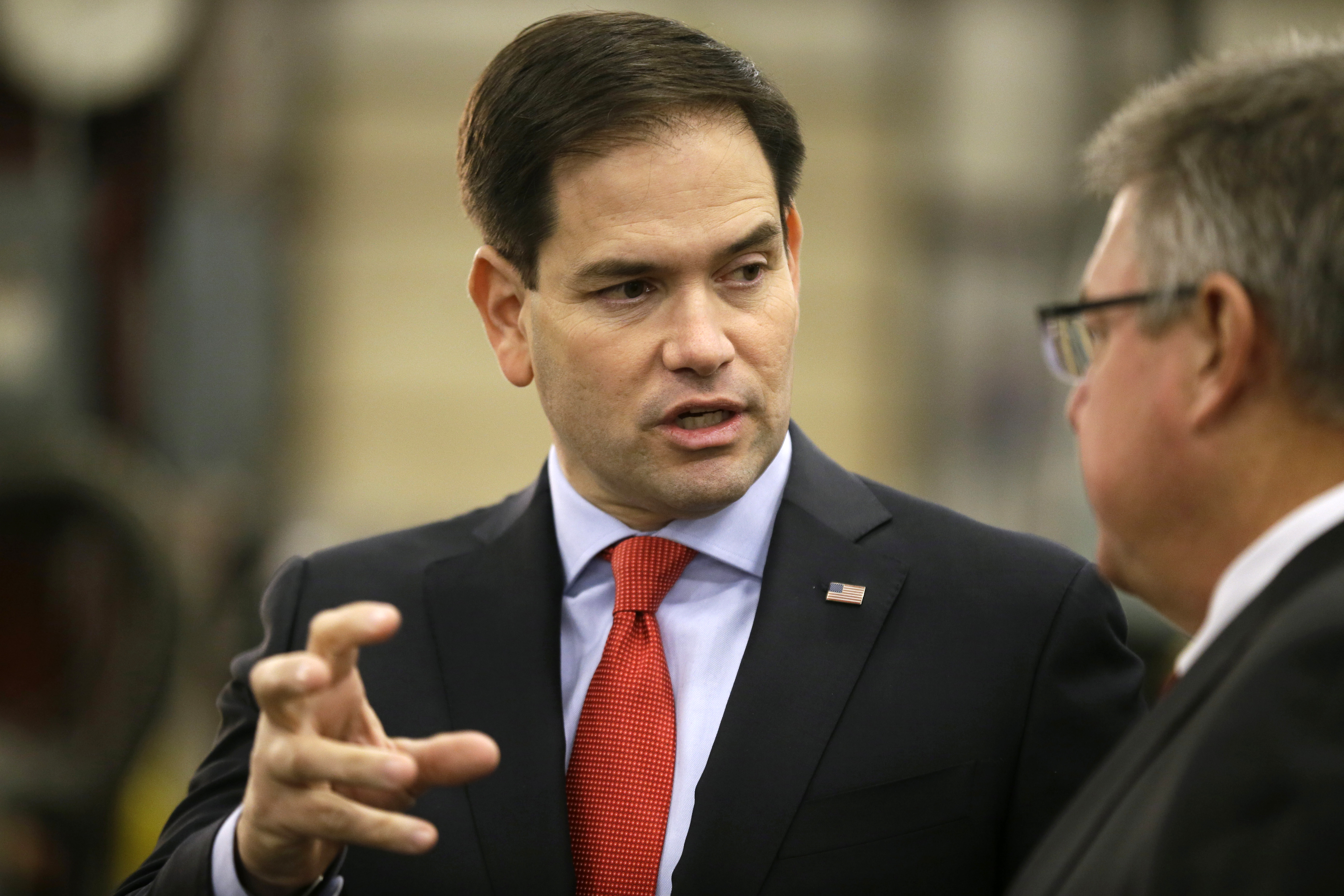

All of a sudden the political media is replete with stories about Marco Rubio, the lazy campaigner. The Washington Post has a big story on how Republican activists in early primary states “are alarmed at his seeming disdain for the day-to-day grind of retail politics.” The Post story followed a National Review piece on how Rubio’s “light footprint on the ground has increasingly become a source of controversy in Iowa and New Hampshire, where prominent activists and Republican officials believe a robust ground operation is critical to wooing voters who want to interact with their presidential candidates.” And Bloomberg Politics reports today that “Rubio is waging a gamble by running a more national- and media-driven campaign” that puts more of a premium on digital outreach and Fox News hits than it does on traditional retail politics.

It’s a curious strategy, especially since it stands in stark contrast to the way Rubio snatched the Republican Party nomination away from Charlie Crist in Florida in 2010, diligently working to curry favor with GOP voters and activists by “driving his Ford F-150 to every crowd of 15 people he could find in Florida and returning to his West Miami cul-de-sac past midnight day after 16-hour day.” Team Rubio clearly sees something different happening electorally this time around, and in some ways their strategy seems to make sense, but in a lot more ways they look nuts.

Let’s start with the things that make (at least superficial) sense. Running an expansive campaign operation in the early states is a very expensive proposition – Scott Walker was forced from the race because he couldn’t raise enough money to feed his sprawling infrastructure. Rubio’s team has always prided itself on its frugality (they were stealing Wi-Fi from a Nevada pizzeria at one point), and having a “lean” or “nimble” or “some other euphemism for ‘cheap’” campaign apparatus is a terrific way to keep costs low.

There’s also a long-term benefit on not working all that hard to court Iowa caucus-goers. Going all-in for Iowa, as Rubio’s chief non-Trump rival for the nomination Ted Cruz is doing, means taking some extremely hard-line conservative positions that aren’t so easy to defend once you move on to other primary states and the general election. There’s also the fact that Iowa Republicans have, in the last two election cycles, elevated two “outsider” conservative candidates who ultimately fizzled. If Rubio campaigns on his terms and trusts that ad spending, debate performances and the power of personality will be sufficient to power him to a respectable finish in Iowa, he can focus time and money on later states that will likely be more important to his chances.

Of course, there are also the risks, which are considerable. Caucuses are powered by the campaigns’ ground games, and since Rubio isn’t really investing in an on-the-ground operation in Iowa, it will likely cost him support when the caucus rolls around. Rubio is, at the moment, running a distant third in Iowa and right now no one really expects him to win. But there’s a difference between losing and being embarrassed. If Cruz keeps poaching support from Ben Carson and ends up blowing out Rubio in Iowa, his “light footprint” strategy won’t be looking so hot.

And that’s what makes it all the more puzzling that he’s also keeping his distance in New Hampshire. The Granite State is, right now, the last redoubt for the mish-mash of candidates who are vying for the backing of the Republican establishment – Jeb Bush, Chris Christie and John Kasich are all within 5 points of Rubio, and they’re all fighting like mad for the same pot of “moderate” voters. If Cruz (or Trump) comes into New Hampshire with a head of steam from Iowa and consolidates the conservative vote while the rest of the electorate is split between three or four candidates, that could serve up another embarrassing night for Mr. Light Footprint.

The impression that Rubio’s team is giving off is that they just aren’t prioritizing the early states, and they’re not especially subtle about it. “More people in Iowa see Marco on ‘Fox and Friends’ than see Marco when he is in Iowa,” Rubio’s campaign manager told the New York Times, giving every rival campaign a readymade attack on Rubio as distant and disconnected. What’s so weird about this is that voters in those states are clearly receptive to Rubio as a candidate, but he’s just not giving them much to chew on besides some ad spending and the infrequent debate nights. The question that arises from all this is whether their candidate can win the nomination without actually winning the early contests that have historically determined the nominee. Rubio’s team seems to think so, and they’re basing it on a novel theory of politics that assumes a good debate performance is a lasting commodity, while an in-person voter interaction is an ephemeral waste of time.