You don’t have to look far on the American left to find accusations that Hillary Clinton is essentially a Republican, or almost a Republican, or simply too damn close to being a Republican. At least I don’t: I’ve done it myself, very recently, in a throwaway jibe partway through a recent article on the GOP’s spectacular implosion. I was aware, even as I wrote that, that it’s only partly true. If the joke stings, that’s because it cuts closer to the bone than Clinton supporters and Democratic Party loyalists would like. But it’s imprecise at best; even in his harshest criticisms of Clinton, Bernie Sanders has never suggested that she might, y’know, be like that.

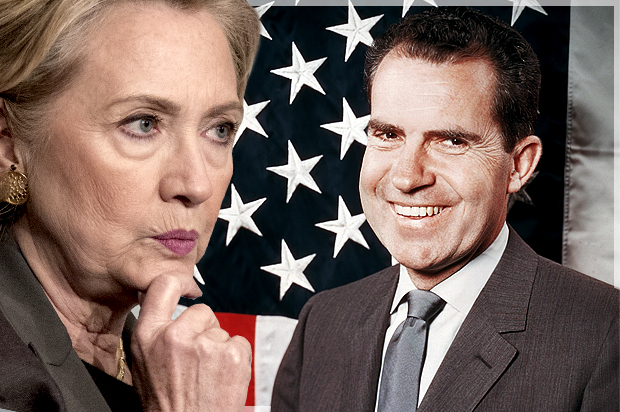

Part of the problem is definitional and historical, and maybe even epistemological. What do we mean by “Republican”? A Republican where, and when? In broad strokes of politics and policy, Clinton is a lot closer to the worldview of Richard Nixon — the president who funded Planned Parenthood and proposed a national single-payer healthcare plan — than Donald Trump is. (Less charitably, we could mention Clinton’s recent reference to her good friend Henry Kissinger, one of the moments of 2016 she definitely wishes she could take back.) But the Richard Nixon who got elected in 1968 would not be a remotely viable presidential candidate in today’s GOP, and quite likely would not be a Republican at all.

So no, those things don’t make Hillary Clinton a Republican. Let’s say this all together: She’s a Democrat — a Democrat of a specific vintage and a particular type. At least in her 2016 incarnation, Clinton is an old-school Cold War liberal out of the Scoop Jackson Way-Back Machine, a believer in global American hegemony and engineered American prosperity. (I realize that’s a completely obscure reference to anyone under 45 or so. We’ll get back to it.) Many such Democrats became Republicans after 1980 — in several prominent cases, the Cold War liberals of the 1970s became the George W. Bush neocons of the 2000s — but Clinton didn’t exactly do that, and that’s not my point.

Clinton’s problem, or let’s say the crux of her many problems, is that the machine dropped her into the wrong decade. She has no Cold War to wage against a monolithic ideological nemesis, only an endless, borderless and profoundly unsatisfying conflict against a nebulous, Whack-a-Mole enemy. She faces a public ground down and demoralized by 15 years of pointless warfare and empty paranoia. Clinton’s version of liberalism — she has earned that label, in all fairness — has been rebranded and reconfigured so many times no one could possibly keep track of its current contents. Her politics are like Doctor Who’s flying phone booth: Until you open the door, you have no idea what’s inside.

Clinton has assumed for decades that her understanding of American politics and the global order, shaped by the Cold War liberalism of her youth, is rooted in unshakable reality and represents a finely calibrated blend of idealism and pragmatism. Whether or not she’s right about that is a matter of interpretation, but here’s a fact: She now finds herself at a moment of unexpected political turmoil, when all her underlying assumptions about reality are under attack. It remains likelier than not that she will win this election — but how confident do you really feel about that? Clinton has clearly been taken off guard by the rise of Bernie Sanders on her left and Donald Trump on her right (if that’s where he is at the moment), and is struggling to catch up to a sudden shift in the political tide that threatens to leave her stranded.

You don’t encounter much discussion of Cold War liberalism these days, at least outside American history seminars. But it lies at the heart of the Democratic Party’s recent history and its current dilemma. As this anonymous post published on the Progressive Historians blog just before the 2008 campaign suggests, Cold War liberalism never really went away. It changed its form and its name but continued to drive the internal politics of the Democratic Party (and drain away its soul). It drove the botched and uneven “humanitarian interventionism” policies of the Bill Clinton administration, and drove Democrats’ unquestioning capitulation to George W. Bush’s Iraq war, the Patriot Act and every other form of hysterical, paranoid and hyper-militarized response to 9/11.

Intriguingly, Cold War liberalism made a brief but striking reappearance in mainstream media discourse late in the Bush-Cheney era, not long before that Progressive Historians post was published. Peter Beinart, then a contributor to the New Republic (the Bible of Democratic centrism, published a semi-influential book in 2006 arguing that a juiced-up, 21st-century reboot of Cold War liberalism was the Democratic Party’s best path forward and the best way to win the “war on terror.” It’s hard to discuss that premise calmly, without insane laughter and an overwhelming urge to drink a mixture of Drambuie and drain cleaner, but let’s try.

In Beinart’s account, Cold War liberalism had effectively disappeared with the rise of Reagan, but needed to be resuscitated. His rendition of CWL history is relentlessly sunny and almost hilariously selective: You won’t read about CIA-sponsored coups or American support for murderous right-wing dictatorships in his book, and he skates right over the Vietnam, where CWL orthodoxy met its doom. Although the Iraq war had gone well south by 2006, Beinart appears not to have noticed that it stemmed from the same impulses and had the same outcome. He’s a skillful prose stylist whose primary mission is to build an intellectual defense of the CWL tradition as a vision of American imperial power and its limitations, with quotations from semi-forgotten postwar titans like theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and foreign-policy mastermind George F. Kennan.

I would bet the ranch that Hillary Clinton read Beinart’s book. Barack Obama (who frequently cites Niebuhr as an influence) probably did too. In any event, the policies they pursued in the Middle East and around the world, beginning in 2009, seemed inspired by the convoluted doctrines of Niebuhr and Kennan and by what Beinart calls “the irony of American exceptionalism”: We have a unique role as global superpower and supercop, and a unique responsibility to scrutinize the morality of our own actions. Which possesses a certain theoretical elegance — if you can stomach the unbearable, preening arrogance behind the whole thing — but hasn’t worked out too well in practice.

Understanding the paradox of Cold War liberalism is crucial to understanding the paradox of Hillary Clinton — and the possibilities, for good or ill, of a Clinton administration that might take office next year. Cold War liberals of the golden age were internationalist hawks who favored an aggressive global policy of American hegemony, and they were also center-left Democrats who supported labor unions and civil rights and a broad range of progressive reforms. If the combination sounds bizarre in retrospect, it made more sense in the ‘50s and ‘60s. In its less hypocritical expressions, Cold War liberalism was about fighting Soviet communism around the world, while smoothing over the contradictions of capitalism and providing wider equality, justice and prosperity at home. Cold War liberals dominated political discourse for almost 30 years after World War II, a period that saw marginal tax rates above 90 percent for the wealthiest Americans and rapidly increasing wages and living conditions for working people.

But Cold War liberalism was about something else too: Crushing most kinds of Third World nationalism (since virtually by definition they were insufficiently pro-American and pro-capitalist) and purging all forms of radical and leftist ideology (whether socialist or anarchist or something-else-ist) from the Democratic Party and the labor unions and other major institutions of American political life. As Beinart mentions in passing, Americans for Democratic Action, a pillar of Democratic Party left-liberal consensus in the ‘60s and ‘70s, began as an organization devoted to rooting out undesirable left-wingers from mainstream politics, and only turned its attention to combating enemies on the right once that first battle had been won.

No doubt the drive to purge suspected Commies and fellow-travelers reflected genuine ideological commitment in some cases, but it was mostly about fear and calculation. With Republicans hammering away at Democrats for being “soft on Communism” and “losing China,” and Joe McCarthy hunting Red spies in the State Department and the military, even the faintest tinge of pink in the Democratic coalition was viewed as electoral suicide. Cold War liberalism as an enterprise was devoted to proving that Democrats could be patriotic Americans and fervent anti-Communists, to the point that its leading figures often appeared more confrontational and militaristic than any Republican. It was Nixon, after all, who flew to China and shook hands with Mao Zedong; no Democrat would have dared to do that.

By the time Hillary Clinton had her famous undergraduate conversion, and resigned the presidency of Wellesley College’s Young Republicans to go ring doorbells for Eugene McCarthy in New Hampshire, she had presumably turned against the Vietnam War. As an adult politician, however, she has come full circle, and now belongs to the tradition of mainstream war-hawk Democrats whom McCarthy attacked — the Cold War liberal cadre of Lyndon B. Johnson and Hubert Humphrey and the aforementioned Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington, aka “the senator from Boeing.”

No contemporary political figure is more clearly Scoop Jackson’s heir than Hillary Clinton: He had close ties to labor unions and shadowy connections to large and powerful corporations; he carefully cultivated relationships with the Civil Rights movement and the African-American community, although he came from a largely white state. He never met any form of military spending or nuclear-arms buildup he didn’t like, and never wavered in his support for the Vietnam War. He was perhaps Israel’s staunchest defender in the Senate (although he was not Jewish) and favored saber-rattling confrontation with the Soviet Union over détente. Jackson died in 1983 and never got to see the rise of the national-security state and the coming of secret, permanent warfare, but the foreign policy of the Bush-Cheney years — and arguably the Obama years too — is his legacy. Richard Perle, Paul Wolfowitz and Elliott Abrams, leading neocons of the Bush administration, were all former Jackson aides.

Jackson was a lifelong foe of the radical left who became the leading figure in a last-ditch effort to deny George McGovern the Democratic nomination in 1972. (Since Jackson’s politics were virtually indistinguishable from Richard Nixon’s, that would have been a strange campaign.) But this maddening and fascinating figure, who authored a world of good and a world of bad, also understood that his war-hawk, missile-building agenda had to be rooted in progressive social and economic policies that rewarded working-class and middle-class Americans for their support. That aspect of Cold War liberalism is barely imaginable today. Jackson would no doubt have been horrified by the rise of Bernie Sanders, who represents the long-delayed resurgence of the anti-capitalist dissent Cold War liberalism was designed to suppress. But Jackson would also have grasped that the Democratic Party’s multiple failures of politics and policy paved the way for the Sanders insurgency.

Hillary Clinton would like to be the figure who finally brings Scoop Jackson’s politics to the White House. It’s difficult to tell the difference between sincerity and artifice with her, but I’m inclined to see Clinton’s recent pivot toward Sanders-lite economic populism as reflecting some genuine conviction. But she faces two big problems, before we even get to the unpredictable opponent who will shift positions daily and attack her from the left and right simultaneously.

One of those is that Clinton is stuck with the hollowed-out remnants of the Democratic Party, which during her husband’s tenure abandoned ideology and severed its connection with class-based progressive politics, in the delusional belief that permanent prosperity would lead to permanent victory. Instead it created economic disaster and spectacular defeat, and despite its supposed demographic advantages has virtually been wiped out across the middle of the country by an overtly racist opposition party that isn’t entirely convinced the earth is round.

Then there’s the bigger problem that no one really wants the ideological package Clinton is selling. She isn’t a Republican, and in fact she’s closer to being an old-line Democrat than her husband ever was. (She was never completely sold on Bill’s “New Democrat” crap.) She’s been inside the defensive Democratic Party carapace of Cold War liberalism for so long, believing it to be the only possible reality, that she hadn’t noticed until right now how much the political landscape had shifted. There are voters who want war, no doubt, and voters who want liberalism. But they aren’t the same people; the connection has been severed. Cold War liberalism, in 2016, is a political philosophy with a constituency of one. To use a reference Hillary Clinton will get immediately, one pill makes you larger and one pill takes you small. Taking both at once doesn’t do anything at all.