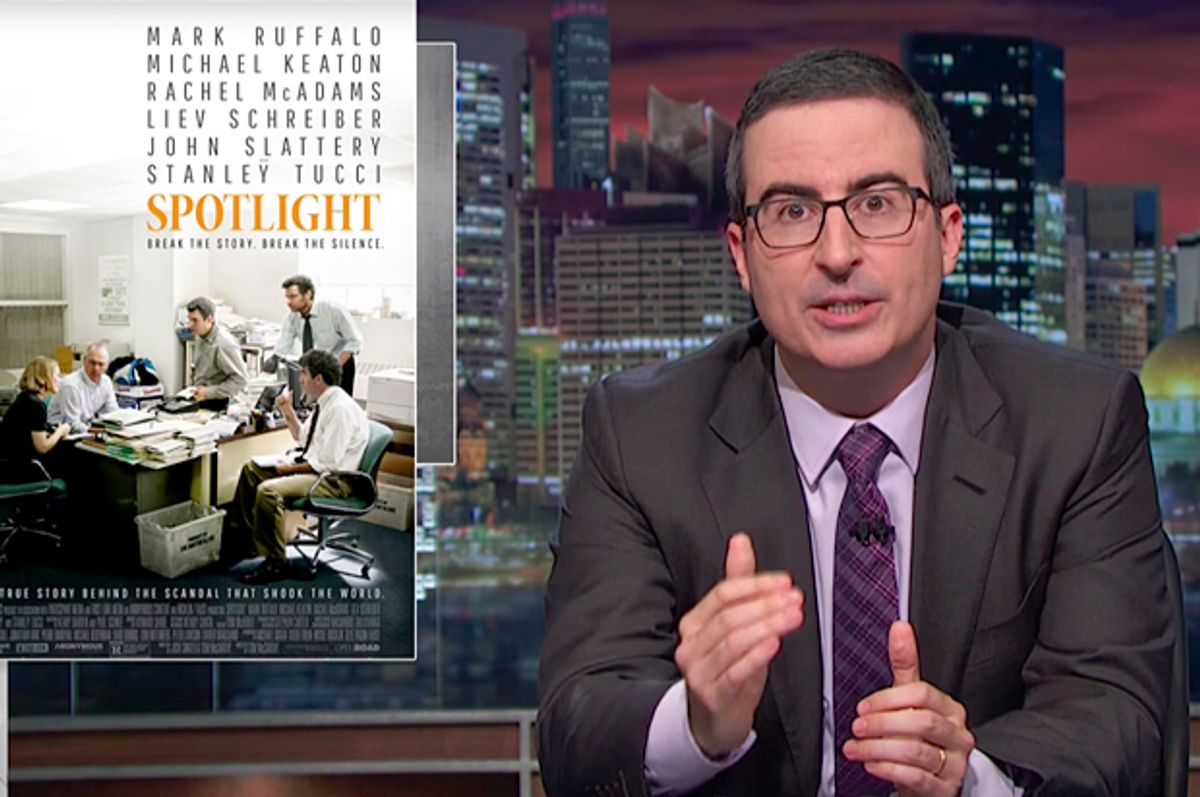

John Oliver’s strength at taking tedious or complicated subjects and making them accessible, even hilarious, is one of the wonders of television in the 21st century. This talent was in full force Sunday night, when he spoke about the struggle of newspapers and the price we all pay for declining local news coverage. For journalists and those who follow the media, his 19-minute rant on “Last Week Tonight” — well, a rant plus a hilarious parody of the movie “Spotlight” — brought some much-needed attention to a story that the general public doesn't understand in much detail.

“We know that we do something hugely important,” Washington Post media critic Margaret Sullivan told me via email, “and we've watched it being not-so-slowly destroyed by forces beyond our control — the biggest one of which is the precipitous decline in print advertising which paid the bills for so long.”

For members of a profession that’s seen tens of thousands of jobs lost, or readers who’ve seen their local paper wither over the last decade or so, the episode probably did not add a huge amount of new information. But Oliver’s genius at being “witty, profane, and at the same time dead serious,” as Rick Edmonds of the media site Poynter put it, was valuable nonetheless. Even people who rarely defend the mainstream media — conservative talk-show host John Ziegler, for example — praised the work of the left-leaning “Last Week Tonight.”

So part of what’s interesting about Oliver’s bit — which looked at both the causes of the decline as well as the effects, with his usual combination of hyperventilating moralism and comic exaggeration — is that some seem frustrated with it. And not just people who hate the press, but people who value what it does.

The most visible of these criticisms so far has come from the president of the Newspaper Association of America, who praised the segment's opening. “But making fun of experiments,” David Chavern wrote, “and pining away for days when classified ads and near-monopolistic positions in local ad markets funded journalism is pointless and ultimately harmful.”

Sullivan, who was once the executive editor of the Buffalo News and the public editor of the New York Times, hit back sharply in a Post piece:

Actually, no. What Oliver did was precisely nail everything that’s been happening in the industry that Chavern represents: The shrinking staffs, the abandonment of important beats, the love of click bait over substance, the deadly loss of ad revenue, the truly bad ideas that have come to the surface out of desperation, the persistent failures to serve the reading public.

Sullivan’s piece is pretty complete and needs little assistance from me. But I’ll just add, in Oliver's defense, that no news story or TV coverage needs to solve all the problems it identifies. Part of the reason that the cult of “free” has been able to erode the revenues of musicians, photographers, and journalist so deeply is that the general public has not understood the overlapping crises and their stakes. To David Boardman, dean of Temple University’s journalism school, the Oliver segment “made a persuasive case that all Americans should be concerned about the fate of newspapers and should do what they can to support their local paper.”

The other main critique of Oliver’s performance was that it was unhelpfully moralistic. A professor and blogger for the London School of Economics, Charlie Beckett, challenged the comedian’s argument that local journalism has a moral function. When journalism tries to appeal to people’s “noble instincts,” as Beckett puts it, rather than generating something people want, it takes its place alongside every other charity. Instead, other publications, like The Economist and the Financial Times, give readers something valuable, and are kept alive by subscriptions: It's better, he says, than guilt trips.

As Beckett writes:

Journalism – as the industry it has been for the last few decades – has no right to exist. It must fight for attention in a world of digital distraction. If that means becoming a spectacle (like John Oliver) then that’s fine. It’s what keeps us honest.

Oliver’s comic sermon suggests the choice is between kittens and investigative journalism when in fact journalism has always been a mix of both. It has always been a combination of circus and pulpit. Create real value for people out of that and they will pay.

Beckett’s point of view is a smarter and more eloquent version of something that many people have been saying about journalism, and many kinds of culture, for years: If it was any good, it would pay for itself. The best rebuttal for this is a line Oliver used: “Sooner or later we are either going to have to pay for journalism,” Oliver said. “Or we are all going to pay for it.”

Similarly, former Baltimore Sun reporter and creator of “The Wire,” David Simon, testified before the U.S Senate, "The day I run into a Huffington Post reporter at a Baltimore Zoning Board hearing is the day that I will be confident that we've actually reached some sort of equilibrium," he said. "There's no glory in that kind of journalism, but that is the bedrock of what keeps [corruption at bay]. The next 10 or 15 years in this country are going to be a Halcyon era for state and local political corruption.” (Oliver’s segment pointed out that recent years had seen a 35 percent decline in statehouse coverage.)

There’s one place where Oliver’s segment was incomplete — which is inevitable even in an intelligent show like his — and that’s in his discussion of what new media can offer. A lot of it is indeed shallow: As son of a Baltimore Sun editor, and a veteran of the Los Angeles Times before Sam Zell trashed the joint, I prefer much of what came before. But while most of them struggle for funding, there are indeed smart local online sites, most of them nonprofits. Here in L.A. there’s a site called Zocalo Public Square that runs essays and stories about big-picture social, political, and cultural issues. San Diego, a city that’s mostly been poorly served by its local newspaper, has a member-supported site with reporters covering politics, health care, water, and land use.

The editor in chief of Voice of San Diego, Scott Lewis, says he enjoyed Oliver’s report. “I would have loved a shout-out to the sector,” Lewis explained via email, “but he laid out my basic stump speech in a much more compelling and funny manner. His plea, that people pay for local news, was key and people should know that nonprofit newsrooms across the country are providing a direct avenue for that expression of support.”

You can disdain the decline of papers, ownership by people like Sheldon Adelson, and the cluelessness of most of what tronc (formerly known as Tribune Publishing) seems to be up to and see a few good things blooming around the edges of the destruction.

Alas, not every city has sites as good as this, and even the best sites rarely do the kind of reporting that keeps communities and local governments functioning smoothly.

Sullivan’s Post piece points out the most important thing about Oliver’s segment was not any detail but the overall force of his delivery. The “day-in, day-out reporting that is the backbone of local newspaper journalism is seriously threatened,” she wrote. “That he was able to make the value of that so clear to a large audience was a real gift.”

Shares