In the past several years, many trees have been felled and pixels electrocuted in the service of discussion about the impact of Hispanics on the American electorate. No one knows for sure which way they’ll vote in the future but everyone is interested in discussing it. Curiously, though, an even larger political shift is taking place yet receiving almost no attention whatsoever from political reporters — the emergence of post-Christian America.

Judging solely from the rhetoric and actions of the candidates who sought the Republican Party’s presidential nomination this year, you would be hard-pressed to tell much difference between 2016 and 1996, the year that the Christian Coalition was ruling the roost in GOP politics. Sure there was a lot more talk about the Middle East than before, but when it comes to public displays of religiosity, many of the would-be presidents have spent the majority of their candidacies effectively auditioning for slots on the Trinity Broadcast Network.

Even Donald Trump, the thrice-married casino magnate turned television host, went about reincarnating himself as a devout Christian, despite his evident lack of familiarity with the doctrines and practices of the faith.

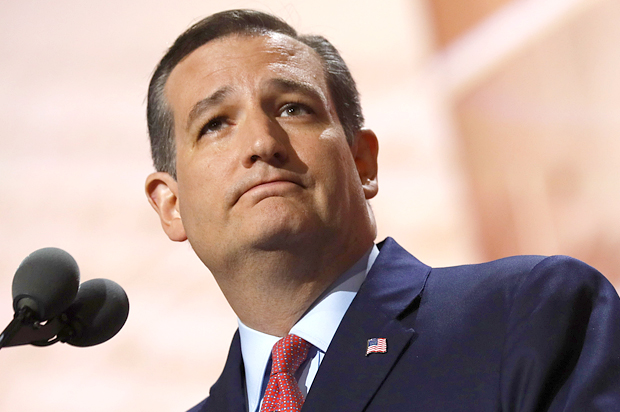

Former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee and former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum, both of whom won Iowa in past years, dropped out after failing dismally in the Hawkeye State’s caucuses. Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal quit months before even a single vote had been cast. Texas Senator Ted Cruz, despite being significantly better financed and supported by more conservative leaders than previous Christian nationalist candidates, was barely able to win any primary states at all; his main strength was in caucus states where popular appeal wasn’t as important.

But Cruz’s difficulties were no different than those faced by previous Christian Right presidential candidates; none has ever even gotten close to the nomination. Cruz’s failure to get the nomination even in the face of the GOP voters’ knowing that an orange buffoon would get it instead is a perfect window into trends that will set the pace of American politics for decades to come: Americans are moving away from Christianity, including people most likely to vote Republican.

While the process of secularization has been slower-moving in the U.S. compared to Europe, it is now proceeding rapidly. A 2014 study by Pew Research found that 23 percent of Americans say they’re “unaffiliated” with any religious tradition, up from 20 percent just three years earlier. The Public Religion Research Institute confirmed the statistic as well with a 2014 poll based on 50,000 interviews indicating that 23 percent of respondents were unaffiliated.

The trend away from faith is only bound to increase with time. According to Pew, about 36 percent of adults under the age of 50 have opted out of religion. At present, claiming no faith is the fastest growing “religion” in the United States. Between 2007 and 2012, the number of people claiming “nothing in particular” increased by 2.3 percent, those saying they were agnostics increased by 1.2 percent and those claiming to be atheists increased by 0.8 percent. No actual religious group has experienced anywhere near such growth during this time period.

Looked at over the longer term, the trend is even more discernible. In 1972, just 5.1 percent of Americans said they had no religious affiliation, according to the University of Chicago’s General Social Survey. In 2014, that number was 20.7 percent, an increase of more than 400 percent.

To put that growth in perspective, consider that Hispanics were 4.5 percent of the U.S. population in 1970 (according to the Census Bureau) and 16.9 percent by 2012 (according to GSS). Despite receiving almost no attention whatsoever, people with no religion are both more numerous and increasing their numbers at a faster pace than people of Hispanic descent. (Unfortunately GSS did not measure Hispanic origin until 2000 so the comparison isn’t completely perfect.)

While those statistics on the growth of religiously unaffiliated Americans ought to be impressive enough to warrant serious discussion, the reality is that public polling almost certainly underestimates the numbers of the faithless because many religious Americans have strongly negative opinions of those who are atheists or agnostics. This negativity makes non-believers less willing to publicly admit to their opinions.

A 2014 study by the Public Religion Research Institute found that people of all races and religious creeds (or lack thereof) were more likely to claim they attended church services in a telephone survey than they were during a self-administered web survey where their opinions would not be solicited by a person in conversation.

According to the research, religiously unaffiliated people were 18 percent more likely to say they attended church services on the phone than they were online. Americans in general were 13 percent more likely to give the religiously correct answer in a phone survey.

The Religiously Unaffiliated are More than Unchurched

Of the few conservatives who have actually responded to this momentous demographic development, the typical response has been to claim that this large group of non-believers are simply “un-churched.” Over time, the argument goes, these people will return to the sanctuary and back into the Grand Old Party. The argument might be a comfortable one to conservatives of faith, but it is not supported by the facts.

When asked to identify their specific beliefs about the nature of God for a 2008 poll by the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), 7 percent of respondents with no religious affiliation advocated an atheist perspective, 35 percent were agnostics, and 24 percent were deists. Just 27 percent of respondents said they “definitely” believed in a personal God. In a private online survey conducted by the Public Religion Institute, just 19 percent of the religiously unaffiliated agreed with the statement that “God is a person.” Forty-three percent of respondents said they did not believe in God while 35 percent said that they believed God is an impersonal force.

While some of those who are unaffiliated do profess a belief in God, a huge majority of those with no religion appear utterly uninterested in joining up with any particular faith tradition. A full 88 percent told Pew they were “not interested.” That is likely because Americans of no faith have strong, negative viewpoints about religious organizations, overwhelmingly characterizing them as “too concerned with money and power, too focused on rules and too involved in politics.” Nearly half of these individuals describe themselves as neither spiritual nor religious.

While religiously unaffiliated people in days gone by might have been “unchurched,” this is no longer the case.

Fewer Christians Means Fewer Republicans

The implications of Americans’ exodus from cultural Christianity are significant for the political right because the religiously unaffiliated appear to have a real preference for Democrats. In fact, a person’s religious perspective is generally the most accurate predictor aside from party identification of how he or she will vote.

It is this changing aspect of the electorate that will have more of an impact on the conservative movement’s future than any other demographic shift. Already, it has decimated Republican vote totals in many western states such as California, Montana, New Mexico and Colorado. True, California and New Mexico have substantial Hispanic populations but Montana does not and neither does Northern California, the furthest left region of the Golden State. The fact of the matter is that many white voters are abandoning faith and as they do, they are leaving the Republican Party as well. Many younger white voters are never even joining up with religion—and the Republican Party by extension. This demographic trend is creating what might be called the “Godless Gap,” a voting disparity that is particularly harmful to Republicans since Democrats have been much better at getting votes among Christians than the GOP has among the irreligious.

While secular people have always favored Democrats for as long as the data goes back, the situation has actually become even worse in recent years for the GOP. Republicans have long trailed Democrats among non-religious Americans (hereafter called “Nones”) but since the late 1990s, they have even been behind independents, according to GSS. Research conducted by ARIS also confirmed this overall trend even though it did not ask people to indicate a party toward which they might incline.

In the 1990 ARIS study, 42 percent of respondents who claimed no religion said they were “independents,” 27 percent said they were Democrats, and 21 percent said they were Republicans. According to the 2008 poll (the most recent), 42 percent of people with no religious affiliation said they were “independents,” 34 percent said they were Democrats, and just 13 percent said they were Republicans.

A 2012 survey by Pew Research confirmed this trend as well. Asked about their voting preference during the previous presidential election cycle, people of no faith said they had voted in about the same proportion for Barack Obama as white evangelical Protestants did for John McCain. Pushed to identify their own partisanship, a full 63 percent said they favored Democrats. Just 26 percent said they leaned toward Republicans.

If partisanship and religious identification were actually independent of each other, this type of shift would not be nearly so pronounced since as the ranks of the non-religious grow, they ought to be exhibiting characteristics more in common with the general population, as one can observe when one examines Nones in non-political contexts such as incomes, divorce rates and (to a lesser degree) racial composition. And yet that is not what appears to be happening when we examine their political preferences.

The likely reason why Republicans have declined in popularity among the non-religious is GOP’s long habit of identifying itself as a Christian party. The later attempt to add in a “Judeo-” prefix has done little to stop the bleeding.

As increasing numbers of whites and Asians have chosen non-Christian religions or no faith tradition at all, they are also leaving the Republican Party. Some are joining up with Democrats but many are choosing “none of the above,” just like what they are doing with religion. Much of this movement parallels already established patterns observed by Jewish voters, who were much more inclined toward Republicans before Christian nationalism became a force within the party.

Republicans Probably Lost Young Adults Due to Decline of Faith

As has already been noted, people claiming “no religion” in surveys are much more likely to be young. As mentioned above, just over 30 percent of adults between the ages of 18 and 29 are Nones. But generational attrition—the gradual replacing of older religious people with younger secular ones—is not the only reason why the ranks of the Nones have expanded. People under 65 have also become more secular in recent years. As noted by Pew:

Generation Xers and Baby Boomers also have become more religiously unaffiliated in recent years. In 2012, 21 percent of Gen Xers and 15 percent of Baby Boomers describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated, up slightly (but by statistically significant margins) from 18 percent and 12 percent, respectively, since 2007.

Their lack of interest in religion is having an effect on the voting patterns of younger Americans. After winning voters ages 18-29 in the 1972, 1984 and 1988 presidential elections (Reagan lost them by one point in 1980), the best the Republican Party has done among this age group is a 47-47 tie in 2000. Even that was a hollow achievement, however, because 5 percent of the young voted for left-wing Green Party candidate Ralph Nader.

In 2004, with Nader no longer a factor, young voters broke for Democrat John Kerry 54 percent to 45 percent. In 2008, Democrat Barack Obama won 66 percent of their votes to John McCain’s meager 32 percent. In 2012, Obama did slightly worse among this age group (which is almost a given since he did so well the first time). He still overwhelmingly won their votes 60 percent to 37 percent, however.

The past shows that young people are not natural knee-jerk Democrat voters, but clearly Republicans have been losing younger voters lately. Religious differences are almost certainly a factor. According to a 2014 poll commissioned by the American Bible Society, just 35 percent of adults between the ages of 18 and 29 believe the Bible “contains everything a person needs to know how to live a meaningful life.” The millennial generation is also much more skeptical about the role of the Bible within society. Just 30 percent of that age group surveyed said they thought the Bible had “too little influence” on Americans. By contrast, 26 percent said the Bible had “too much influence” on society.

The “Godless Gap” and the 2012 Election

Beyond the national trends, the increase in secularization has also had an effect in the different regions of the country where Nones are concentrated. As noted by the 2008 ARIS study, 20 percent of people living in California, Oregon and Washington were non-religious, 19 percent of people in the Mountain West were Nones, and a full 22 percent of individuals living in New England had no religious faith.

It is no coincidence that as non-belief has increased in these regions, the Republican party’s fortunes there have declined accordingly. The 2012 election provided many examples of how Republicans are losing elections thanks to the Godless Gap. In seven key states (Pennsylvania, Florida, Virginia, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa and New Hampshire), Mitt Romney won the majority of the Christian vote but ended up losing overall because he was defeated so soundly among non-Christians.

2012 Presidential Vote by State and Religious Belief

Source: Exit poll conducted by Edison Media Research

| State | Protestant Obama | Protestant Romney | Catholic Obama | Catholic Romney | Unaffiliated Obama | Unaffiliated Romney |

| Iowa | 46 | 53 | 47 | 52 | 75 | 22 |

| Florida | 42 | 58 | 47 | 52 | 72 | 26 |

| Pennsylvania | 49 | 51 | 49 | 50 | 74 | 25 |

| Virginia | 45 | 54 | 45 | 55 | 78 | 22 |

| Wisconsin | 45 | 54 | 44 | 56 | 73 | 25 |

| Michigan | 48 | 51 | 44 | 55 | ||

| New Hampshire | 42 | 56 | 47 | 53 | 73 | 26 |

Even though the state is famous for its religiosity, in Iowa, Nones were indisputably the margin of victory for Obama. According to exit polls, Romney won the votes of the 62 percent of Iowans who called themselves Protestants (53-46) and the Catholic 26 percent (52-47) but he overwhelmingly lost the None vote 75 to 22 percent. With its overwhelmingly white population, Iowa was Romney’s to lose. And he did—by doing so poorly among white voters with no religious affiliation. In the end, the former Massachusetts governor lost the Hawkeye State by less than 100,000 votes.

Non-Christians also put Obama over the top in Pennsylvania, a state which Romney’s top advisers believed was “really in play” right up until Election Day. And they were right—so long as one only looked at the vote of the Christian faithful (77 percent of the electorate). Romney actually managed to win both the Protestant and the Catholic votes quite narrowly, 51-49 and 50-49 respectively, but his tremendous loss among the 12 percent of Pennsylvanians who were not religious overwhelmed his share of the Christian vote. Because he lost the None vote 74-25, Romney ended up losing the state 52 to 47 percent.

The same thing happened in Florida as well, another state that Romney was counting on winning. He cleaned up among the 51 percent of Protestant voters (58-42), won the 23 percent Catholic vote (52-47) but ended up losing the 15 percent None vote 72 percent to 26 percent. He also sank among the non-Christian religious as well. In the end, Romney lost the state by just 74,309 votes. Had he done just a little better among non-Christians, Romney would have been able to put the Sunshine State into his column.

Virginia was another state that was Romney’s to win had he done better among non-Christians. According to exit polls, Romney captured small majorities among Protestants (54 percent to 45 percent) and Catholics (55 to 45) but was clobbered among non-Christian believers (78-22) and among those with no religion (76-22).

The None vote also cost Romney the state of Wisconsin. As with the other states examined above, Romney won the Catholic vote (56 percent to 44 percent) as well as the Protestant vote (53 to 45 percent) but lost so overwhelmingly among non-believers (73 to 25 percent) that he ended up losing the Badger State 53 to 46 percent.

The same thing happened in Romney’s native Michigan, where he won among Protestants 51 to 48 percent and among Catholics (55 to 44 percent) but lost so overwhelmingly among non-believers that he ended up losing the state 54 percent to 45 percent.

The former Massachusetts governor also lost New Hampshire despite winning the votes of both Catholics (54 percent to 46 percent) and Protestants (57 percent to 42 percent). Because he lost the None vote so badly (71-28), Romney ended up losing the state’s electoral votes by less than 40,000 votes.

Based on the data above, it is safe to say that the Godless Gap cost Mitt Romney the election.

While many of the Nones who voted against him are hard-core Democrats who never would have considered voting GOP, it is not unreasonable to think that Romney could have done better among non-Christians, especially given the decline in Republican partisanship among Nones mentioned above. Had Romney managed to improve his performance among people who don’t believe the Bible is true, he could have won as many as 304 electoral votes.

GOP’s Choice: Christian Nationalism or Political Reality?

That so many non-Christians would choose not to vote for Republicans and conservatives really should come as no surprise considering the fact that many Christian conservatives—even at the very highest echelons of power and influence—seem to be utterly unaware that their repeated use of Christian symbolism and their insistence on promoting religious liberty only for Christians can be perceived as offensive or non-inclusive to people who do not share their beliefs.

As conservative author Dinesh D’Souza, a Christian immigrant from India, has described it: “Whenever a Gujarati or Sikh businessman comes to a Republican event, it begins with an appeal to Jesus Christ. While the Democrats are really good at making the outsider feel at home, the Republicans make little or no effort.” That’s also true of people who do not believe in any faith.

Even if non-Christians do not take offense at being excluded, at the very least such public displays of Christian belief at ostensibly secular events certainly do not encourage them to participate or to become enthusiastic. National Review columnist Jonah Goldberg (who is Jewish by ancestry although he is non-practicing) described the phenomenon well in a 2012 column:

“I’ve attended dozens of conservative events where, as the speaker, I was, in effect, the guest of honor, and yet the opening invocation made no account of the fact that the guest of honor wasn’t a Christian. I’ve never taken offense, but I can imagine how it might seem to someone who felt like he was even less a part of the club.”

As bad as things are now for Republicans with regard to secular voters, however, they seem to be worsening. A 2012 study by the Pew Research Center found that the Democratic share of the None vote has increased significantly since 2000 when it stood at 61 percent. In 2004 it rose to 67 percent. In 2008, an incredible 75 percent of the religiously unaffiliated voted for Barack Obama. In 2012, not quite as many, 70 percent, did so again. As it stands, people with no faith tradition have shifted a full nine points toward Democrats.

Unless action is taken—and this must include a concession that most Americans support same-sex marriage—as the non-Christian portion of the country continues to grow, the prospects for the conservative movement are going to attenuate as the Godless Gap widens.

Following Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss, there has been a lot of discussion about how conservatives can better reach out to non-whites. The Right will probably need to have a similar discussion about doing the same for non-Christians, especially since many non-whites are also non-Christian.

Regardless of what happens to GOP candidates in November, Christian conservatives face a choice. They can embrace identity politics and become a small group of frustrated Christian nationalists who grow ever more resentful toward their fellow Americans, or they can embrace reality and render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s.

Matthew Sheffield is a journalist currently working on a book about the future of the Republican Party. You may follow him on Twitter: @mattsheffield. This article is reprinted by permission from Praxis.