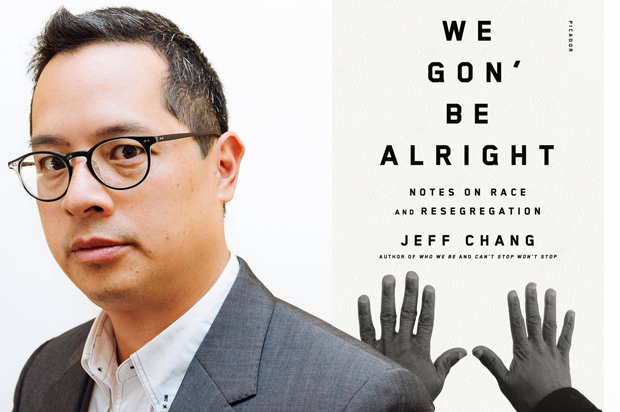

Jeff Chang’s new book, “We Gon’ Be Alright: Notes on Race and Resegregation,” is filled with alarming statistics.

In an essay on race and popular culture, the journalist and cultural critic noted that as of 2014 in Hollywood, “less than 6 percent of executive producers and 14 percent of writers were of color.” Later in an essay on public education, he wrote that in the United States, “Only 8 percent of white students attend high-poverty schools, while 18 percent of Asians and 48 percent of Black and Latino students do.”

Elsewhere, he reported that the African-American rate of premature death — defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a death occurring before age 75 — is 50 percent higher than that of whites. “Racism kills,” he wrote.

Chang’s book is filled with such jolts of cold statistical truth and bracing analysis. To read it is to watch him confidently dive into some of our cultural hot zones — racial unrest on college campuses, the #OscarsSoWhite discussion, the ascendance of Donald Trump, the “hyper segregation” of certain American metro areas — and describe them in ways that make perfect, if disturbing, sense. If future generations ever need an account of America’s current, tumultuous moment, Chang’s book is good place to start.

The book’s longest essay, “Hands Up: On Ferguson,” offers a sweeping look at the events around the August 2014 death of St. Louis teenager Michael Brown at the hands of a white police officer — an event that sparked what one protest leader called, “the longest rebellion in the history of the United States against police brutality.” The debate over whether Michael Brown’s hands were actually up when he was shot missed the point, Chang said.

The image of raised hands “resonated — and would continue to grow in the public imagination — because it captured a bigger truth, a deeper feeling,” he wrote. “‘Hands up’ was about the ways we saw race in post-civil rights America, and perhaps especially about what we refused to see — the blindness of a ‘post-racial’ era. If, as intellectual Ruth Gilmore had written, racism was about the ways in which Blacks, whites, and others differently experienced ‘vulnerability to premature death,’ ‘Hands up’ was an argument for the right to live.”

Salon recently spoke with the Berkeley, California-based author over the phone. The conversation has been edited only slightly for length. When you’re talking about race in America, there’s a lot of ground to cover, and Chang has a lot of good stuff to say.

I want to start with a simple, but complicated, question: Do we live in a segregated country?

Absolutely. I think it’s been the history of the U.S. And what I think we’ve seen over the last 50 years is a steady move back towards resegregation.

You look at 1965, which is the sort of peak of the civil rights movement. [And] since that particular time what we’ve seen is the implementation of many of these laws and judicial decisions that pushed us towards desegregation, and a lot of that peaking in the late ’80s and early ’90s. And since that time we’ve sort of been on a backsliding course towards segregation. And so we’ve entered into a dangerous new phase in which we are experiencing this, but at the same time we are less likely to talk about it than before.

I should qualify that by saying that during the past two years the Movement for Black Lives has forced the question of racial equity back onto the table. But there has not been a national consensus to resolve the issue of racial inequity for 50 years. And so what I was tracking within “Who We Be,” my last book, and this new book, are the sort of quiet, understated impacts of that.

Ferguson is a suburb of St. Louis, Missouri. And while we’ve been talking a lot about gentrification in the cities, we haven’t talked about what it means to have people of color who have been displaced from the cities forced into suburbs that are decaying, declining; that are being defunded; where schools are closing; and where policing is being used as the mechanism to build up tax-depleted city budgets.

That’s essentially the story of Ferguson. And as everybody in Ferguson says, the story of Ferguson is really the story of what’s happening in America right now.

I was struck by excerpts you include in the book from the Department of Justice report on the Ferguson Police Department. One reads, “[Police] are inclined to interpret the exercise of free-speech rights as unlawful disobedience.” And later on, “The result is a pattern of stops without reasonable suspicion and arrests without probable cause, in violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

So in just the excerpt you quote, we have serious First and Fourth Amendment problems. Basically neither is really being observed in Ferguson, according to this report. And I’m reading this and thinking, “This is a deeply un-American place inside of America.”

The thing is, when we have these debates and discussions about race in [the] “post-post-racial” era . . . The “post racial” era lasted all of about three months between November of 2008 and maybe January of 2009, before the backlash started setting in, and then now we’re in the “post-post-racial era.” But in this sort of “post-post-racial” era, I think, one of the things that we’ve completely overlooked is that these types of things are happening across the U.S. There are patterns that are happening across the U.S.

If you want to talk about the center of questions about gentrification and displacement, we can talk about the Bay Area. People talk about Brooklyn; people talk about Washington, D.C.; people talk about Chicago. But the Bay Area is a perfect example of what’s happened. There has been this huge, disturbing and dramatic decline in the African-American population in San Francisco and in Oakland over the past two, three decades.

And many of those folks have moved to Antioch. They’ve moved to San Leandro. They’ve moved to Richmond. They’ve moved to a lot of different places. Such that, now, when you think about the map of hip-hop in the Bay Area — the “Yay Area,” as they call it — it extends from past San Jose and Gilroy, all the way past Sacramento, in the sort of northeastern part of the Central Valley.

Basically people have been scattered to the winds. And what’s happening in these suburbs is that they’re towns that are struggling with [a] low tax base, and so oftentimes — Ferguson was an extreme example — policing becomes the mechanism by which the city budgets get maintained. So they set up debtor’s prisons to cover basic city services.

Again, to quote you quoting the DOJ: “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue, rather than by public safety needs.” It seems like any American reading this would hopefully be upset by that.

You would hope so, right? You would really hope so. I mean, that’s why I’m writing.

The thing is, there’s a pattern. If you look at the [DOJ’s] Baltimore police report, when you look at other things that are happening, we’re really talking about a constellation of issues that are all connected. And it has to do, again, with this question of where wealth is moving to and where poor people are being displaced to — and in particular poor black people and in particular poor people of color.

And then our discussion or conversation about these things focuses on the symbolic rather than the factual. And so people get caught up with slogans that mean nothing like “All lives matter.” And they are missing the chance to be able to really understand what’s at work here, which is a massive reshaping of the geography of poverty and race in this country at this particular moment.

Let’s go back to that term you used: “post-post-racial era.” To apply some mathematics to that, I think, the “posts” would cancel each other out, and we’re back in simply a “racial era,” right?

[Laughs] I think that’s one way to definitely look at it, for sure. Yes, I’m laughing only not to cry because you’re absolutely right.

Do you think a “post-racial” country is a fantasy or an actual attainable reality? And is it something we should even strive toward?

Listen, I, like everybody else, want to live in a society in which we don’t have to talk about racial injustice. [But] I don’t want to necessarily live in a society where my particular cultural background and identity is not respected. And so those are two different types of things.

On the one hand, what people want is not to talk about race anymore. There’s sort of a fatigue around it. And people would prefer to be “colorblind.” [But] well, you know, we all have different kinds of physiognomy, and in this country that’s become a shorthand for cultural difference. I don’t want to be treated as if I’m not of Chinese and Hawaiian descent. I don’t want somebody to look at me and say, “I don’t see color with you. I just see you, as Jeff.” And I’m like, “Well, look, I look this way because I have this kind of a background. It’s just the way that I grew up.”

That’s completely different from the question of what it means to have racial justice and equity. And I think that oftentimes what happens is that the “colorblind” thing gets in the way of us understanding that certain differences are human-made. Racial discrimination is human-made. And the good news it that it can be undone. The good news is that we can address these types of questions if we are able to pull together the sort of community will and the national will to address these issues.

We could talk broadly about why segregation matters. But let’s zoom in on one particular thing that you highlight, which is the link between segregation and economic mobility — or the lack thereof. Can you talk a bit about that link?

Yeah. Segregation doesn’t necessarily only impact this generation. The impacts of inequality continue on for generations if there is not any kind of intervention. So there have been a lot of studies on this where lots of experts agree that after the housing bust of 2008, what we saw was basically a decade or so of marginal gains in [the] closing of the racial wealth gap erased pretty much over night and left at a point that’s even more starkly divided than before. Whereas before it looked like the gap was going to close and, if trends held, we might be able to reverse this within a lifetime, now it looks like it’s going to take a couple lifetimes to be able to get at it.

And so this is the urgency, right? The urgency is that it’s happening right now and affecting people right now. But if we don’t make any kinds of shifts in policy that reverse these trends toward housing resegregation, that reverse these trends toward school resegregation, that reverse these trends around disparities in health, that reverse these trends all across the board — what we’re going to see happening is this continuing into future generations. And that’s a horrible legacy for us to leave.

Malcolm Gladwell did this podcast called “Carlos Doesn’t Remember” talking about how difficult for a super-super bright poor kid of color from Lennox, Los Angeles, to be able to succeed in the long run. And it’s a heartbreaking piece. It’s just one of those things that leaves you devastated.

The statistics show that inequality is greater than it’s ever been. But to be able to really understand these types of stories of what it means to be caught in a situation where one is experiencing the pressures created by class, as well as the pressures created by race — that’s the kind of stuff that we need to understand on a society-wide level again.

Let’s talk about President Obama for a second. At different points in the book, you refer to him as “once the embodiment of cultural desegregation and racial reconciliation” and “for disaffected whites the image of all fears.” Thirty years from now if a student or a child or a grandchild asked, “What happened under the first black president? What was his presidency all about?” what do you think you’d say?

It’s also important to note, too, as a fellow Local person from Hawaii (capital L “Local” person from Hawaii), he grew up in a multiracial society and has proudly represented that as well. The fact that his sister is of Asian descent, his nieces are of Asian descent, that he has white family, black family, Asian family — he’s sort of a picture of a 21st–century American family, a postmodern family, if you will.

So on the one hand, what’s happened, I think, is that he’s come to symbolize the kind of exuberance and hope that many people had after the 2008 election that we had maybe turned a corner. And what I think is more true now is that it’s not necessarily that we turned a corner on resolving these types of questions. But there’s now a much bigger sense of understanding and possibility of what it would mean to be able to develop an American future.

We no longer have to imagine what it would mean to have a nonwhite male leading as the most powerful person in the country and possibly the world. We don’t have to imagine that anymore. My kids have now grown up with having a black president for the majority of their lives. And that’s a really powerful thing.

At the same time, though — and I’m not blaming the president for this — at the end of his presidency, racial tensions seem to be at a level that I haven’t seen in my lifetime.

I would agree with you on that. And I think that’s the other part of it, the hysteria portion of it that’s come into play here. That really Obama has stirred up the sum of all the fears of whites who believe that they may be losing power and [who] project that onto a nonwhite body, onto a black body, as opposed to assigning it to any number of people or actors — corporations, political organizations, what have you — who have been actors in actually pushing us in a direction that leaves us more divided.

So that’s the sort of weird, paradoxical place that we’re in right now. On the one hand, we are capable of dreaming of that kind of “post-racial” paradise in ways that we never could have before. But on the other hand, there’s the sort of — I write about this in the book — the recurring sense of a white apocalypse that keeps on getting brought back around every time Donald Trump steps to the podium. And that I think that ongoing mythology of a white racial apocalypse is something that’s is probably at a higher pitch in the popular culture [now] than at any time since maybe the early 20th century.

For the folks who haven’t read your book, what is exactly is that “white racial apocalypse?”

It’s right there in the core of American popular culture. [It’s] the notion that’s been played out in every John Wayne movie. It’s there in D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation.” The notion that civilized people will be overrun by barbarians.

There’s a point that I make in the book that American popular culture: In some ways, two of the most important founding myths and stories and narratives, tales in American popular culture are the cowboy-and-Indians stories, in which the cowboys are always in danger of being overwhelmed by the Indians, and blackface minstrelsy, in which blacks have been reduced to silly, naive, dumb sort of folks who are meant to be laughed at.

And I think between those two we have a lot more than we actually ever need to know about American popular culture, in a really weird way. And that might sound heretical; and it might sound even crazy for somebody to say that. But to me the notion of the white racial apocalypse, that spreads from the original Buffalo Bill Cody revue to that movie that they made about the Bronx with Paul Newman starring in it, “Fort Apache, The Bronx.”

It’s something that gets re-enacted all the time. It’s one of the oldest stories in American popular culture.

“Diversity” is a charged word that you unpack and examine in many places in the book. And it also pops up, as I saw on the jacket copy, in your job title: executive director at Stanford’s Institute for Diversity in the Arts. What does that word mean to you?

Well, the word “diversity” used to be a radical word. It used to be a scary word. That was after it was a word that meant nothing to people. [Laughs]

So when people start talking about the word “diversity” in the ’70s, it’s sort of this fringe concept that belongs to ecologists — people who are thinking about biodiversity, for instance — and cultural thinkers, people like Alan Lomax and Ishmael Reed. The idea, at that particular point of diversity, is that it’s the natural state of the world and that cultural diversity is in a lot of ways like biodiversity. If you’ve got cultural diversity, and you’ve got this exchange that’s happening, you have the foundations for a really vital community and society.

And so that’s taking it back to the ’70s. By the ’80s it becomes a strange sort of bureaucratic catchword that allows institutions to be able to talk about “affirmative action” and about “inclusion” and about equity for previously underrepresented communities in a way that doesn’t scare the donors [and] the folks who are traditional and fearful of change.

And so by the time get to the end of the ’90s and the turn of the millennium, “diversity” is pretty much the accepted parlance of power. You don’t use the word “equity.” Diversity is the way that you talk about equity without even having to reference the word equity.

Now, at some point, what becomes clear is that diversity and equity are not the same thing. And what I try to do in the book is to outline the idea that diversity was used deliberately by Justice Lewis Powell in the Bakke decision and subsequently by people in power, that diversity was used to replace the concept of equity. And so the question becomes then, “Is diversity really just to satisfy white folks?” To be able to allow white folks to feel they’ve been able to create a society in which we’ve got the window dressing of representation, but we don’t have to deal with the fundamental questions of power and equity?

And so by now, I think, what we’ve seen, especially in of the last year on [college] campuses, is people, especially young people, are willing to challenge the facade and picture of diversity versus the reality of inequity. That the student protests last fall — they weren’t necessarily about these symbolic debates about trigger warnings or “safe spaces.” They were really about the continuing lack of equity that’s happening at these resegregated campuses.

I have to [add] that I do run a program called the Institute for Diversity in the Arts. And the name came in back in 2001 when the institute was founded. And so it’s not that I don’t believe in the word “diversity.” I don’t necessarily even hate the word. It’s that “diversity” has become uncoupled from “equity.” And I think that what we have to do is to be able to recognize that equity is really the goal — that diversity we can simply achieve through the mandatory quotas that there be, say, a black person and a woman speaking at the Republican convention.

The question of equity is completely different. Are there folks in the room who are hammering out the platform? Are real diverse points of view being represented in terms of what is coming out of those kinds of rooms?

Let’s try to end on a more upbeat note. In addition to everything else that’s going on in our country right now, you say that “In its 2016 nominations, the Academy [of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences] ignored what might be called the Black Lives renaissance — the broad, urgent work of Black actors, directors, and others who were telling some of the most important stories of our time.” Let’s focus for a moment on this “Black Lives renaissance.” What do you have in mind when you refer to that?

Oh, so much. So much. Do you have another hour? We could talk about this forever!

I feel like one of the things that the Black Lives Matter movement has done is it’s inspired black artists and creatives to think about not just questions of premature death and extrajudicial murders, but “What does it mean to really live? And what does it mean to put those lives on full display so that people can see black life for its full range of humanity?”

And so I don’t think it’s been a mistake that in the last two or three years, we’ve seen this outpouring of amazing work by so many different kinds of black artists. And I think that that, in turn, has inspired all kinds of communities who feel marginalized and invisible-ized. Certainly they’ve inspired a lot of indigenous folks and Asian-American folks — I can say from personal experience.

And so, within this sort of black lives renaissance lies also the seeds of what could become a really amazing cultural flowering happening here in the early 21st century. And to really reimagine what the multiculturalists were trying to do in the ’70s and ’80s of thinking about the concept of America completely from the ground up. And so when I talk about that, I can easily point to records like Kendrick Lamar’s “To Pimp a Butterfly” like D’Angelo’s “Black Messiah,” like Kamasi Washington, like Noname’s new album, which is so good. Jamila Woods’ new record is so good. Michael Kiwanuka’s album is so good. I haven’t even gotten to the M.I.A. album yet today. I just downloaded it. Vince Staples. You could just go on and on and on. There’s just been amazing work that’s been produced in the last couple of years.

You can look at what’s happening with TV. “Atlanta” debuted this week. You’ve got “M”Mr. Robot,” where you’ve got an Arab-American point of view taking on the national surveillance complex and economic inequality. You’ve got so much amazing stuff happening at this particular moment culturally, and I think that that’s probably one of the most under-sung kinds of things that have happened out of the last two years, in which we’ve seen culturally a tidal of shift in the way we think about and see race in this country.

What can people do, who are reading this article, who are reading your book to in their own small way work against resegregation in this country?

Well, it begins in your community. It begins with looking and assessing where we stand in relationship to these particular kinds of issues. And some people have to travel very far and have to do a lot of listening to be able to get to a place where they can make the changes that they need to make in order to be of help to bringing about a new, transformed society. And some people are much closer to the front lines in experiencing what it means to be oppressed in the kind of way that we understand it in the 21st century.

And those of us who are not on the front lines need to be able to make room for those people to be able to stand up, tell their story and to be supported in their ideas to be able to make change. And I think, again, this leads us back to the moment that we’re in, which is the Movement for Black Lives has I think forced us all to reconsider what our relationship is to questions of racial justice and cultural equity. And so if we begin at home, if we begin with ourselves and do that assessment and then begin the long process of listening and learning, speaking when we need to speak and acting in the way that we need to be able to act together, then we have a shot at this.

I’m ultimately a hopeful person. I’m ultimately a glass-half-full type of person. So, for me, hearing Kendrick’s song in which maybe 90 percent of the lyrics are about struggle and you have this one line, “But, we gon’ be alright,” is something that’s really inspiring to me. I think it’s possible for us to get really pessimistic and despairing about the future. But we can’t. We have to have a reason to be able to get up in the morning and we have future generations to think of and work for.