The idea that Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump is not a conservative or that his rise has nothing to do with the conservative movement was ludicrous on its face from the very beginning.

Sure, Trump is an unorthodox candidate in various ways, but he appeals directly to generations of racial, gender and ethno-nationalist resentments that the conservative movement had repeatedly stoked in its unending quest for power — as I’ve written about in the wake of Ferguson and after Trump’s first black-outreach fiasco.

Trump emerged in a period of flux when no one was quite sure what a conservative was anymore — opposing Barack Obama seemed unquestionably central — and he first made his play for power by striking at the root, seeking to own the birther issue. Sure, he said things that no conservative would normally say. He was an outsider. But as Corey Robin wrote for Salon in March:

Outsiders like [Edmund] Burke or [Margaret] Thatcher — even Donald Trump, who’s never been a Republican, much less an officeholder — have always been necessary to the right. They know how the insiders look to ordinary people — and how they need to look.

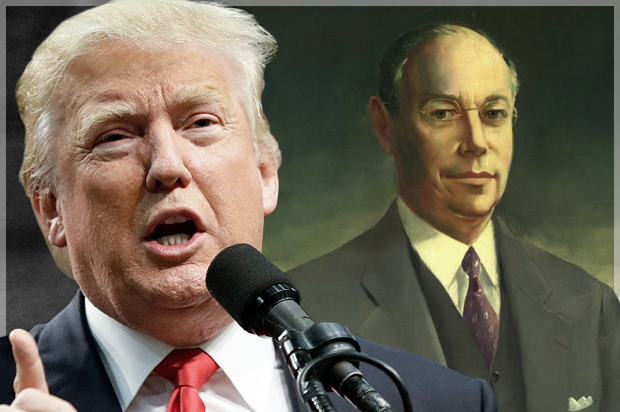

Over the last half year or so, various people have drawn a sharper line. In July, I wrote about Trump’s affinity in general for the branch of right-wing ideology known as “paleoconservatism” and in particular for the ideas of William Lind, a key figure in the recent paleoconservative resurgence.

In August, Timothy Shenk wrote about paleoconservative thinking in the Guardian, tracing it back to James Burnham’s 1941 book “The Managerial Revolution” as it wended its way down through Sam Francis and Jared Taylor.

And even earlier in May, Dylan Matthews wrote a Vox story about paleoconservatism, touching briefly on its earlier prominence (before the term was coined) before the Cold War era, equating it with the old right.

Others have written about it as well, but it’s noteworthy that JSTOR Daily recently ran a story by Matthew Wills headlined “Is the Alt-Right the Grandchild of the Old Right?” This piece highlighted Sheldon Richman’s 1996 article on the old right, “New Deal Nemesis: The ‘Old Right’ Jeffersonians, in the libertarian journal The Independent Review.

As is typical of libertarians, Richman was blind to the role that racism (and anti-Semitism) played in this story — a point that Wills remarked on. But Richman did provide a more focused sense of what distinguished the old right: It wasn’t just the broad, self-interested protectionism described by Matthews and going back to when Republicans like William McKinley “supported tariffs as a way of supporting domestic industries and raising revenue outside of an income tax.”

It was a specific political constellation that formed in reaction to Franklin Roosevelt. First it opposed the New Deal and then his engagement in World War II, but all that was supplanted when the Soviet Union emerged as an even greater perceived threat.

To show how sharply the new right and old right diverged, Richman quoted directly from William F. Buckley, godfather of the modern conservative movement:

In a 1952 article, Buckley called for “extensive and productive tax laws . . . to support a vigorous anti-communist foreign policy.” Because of the “thus far invincible aggressiveness of the Soviet Union,” he stated, “we have to accept Big Government for the duration — for neither an offensive nor a defensive war can be waged . . . except through the instrument of a totalitarian bureaucracy within our shores.” He also wrote, “Where reconciliation of an individual’s and the government’s interests cannot be achieved, the interests of the government shall be given exclusive consideration.”

Such words were heresy to the old right, to which Buckley himself had once belonged. As indeed they would be heresy today — at least as long as a Democrat is in the White House.

The old right of the pre-World War II era had a coherent organizing framework: individual liberty and a decentralized constitutional republic, as opposed to a powerful centralized state, leading to empire. Unfortunately, that made little sense for African-Americans whose only real guarantee of liberty had come via “oppressive state power” depriving slaveowners of their “God-given rights.” As Donald Trump might have tweeted, “Sad!”

More to the point, in terms of sheer realpolitik, millions of others got shafted by this idealized model of perfect freedom, if not quite as dramatically. There was “one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished,” as Roosevelt said in his second inaugural address. And since pragmatism is as American as apple pie, the vast majority did not consider Roosevelt the enemy of real America. They considered him its embodiment.

So the picture Richman painted is intriguing, however flawed, because it shows how movement conservatism has reinvented itself in reaction to perceived real-world threats — which in turn strongly suggests how we should see conservatism reinventing itself today. Not just in the figure of Donald Trump, but through the vehicle of his candidacy, and the broader invigoration of the confrontational, overtly racist and ultra-nationalist “alt-right,” echoing similar movements in Europe and elsewhere.

It’s not a new idea that conservatism reinvents itself in reaction to perceived threats. That’s a central theme in Corey Robin’s book “The Reactionary Mind,” as hinted at in the brief quote from him cited above. What’s helpful here is the strong sense of periodicity, as well as Richman’s description of the way the old right brought together different strands, not all of which were innately or originally right-wing. He overplayed his hand in this regard, but the underlying point is sound: Major shifts in power bring about realignments and formerly progressive forces inevitably turn reactionary, even as formerly conservative forces become radicalized.

“The Old Right began as a group of people with disparate backgrounds but awakened by a common threat: Franklin Delano Roosevelt and unprecedented accretion of executive power,” Richman wrote. He then argued that it was only superficially “conservative,” because FDR’s New Deal policies can be understood in part as a defense of the “corporate, nativist status quo” against the economic revolutions that had created the Depression. So it was that socialist Norman Thomas and progressive Robert La Follette Jr. made common cause with the anti-FDR forces of the old right.

Although the argument is overstated, it contains germs of truth: The progressive tradition on which the New Deal was built had significant corporate conservative roots, as historian Gabriel Kolko argued in “The Triumph of Conservatism,” but it also included La Follette and his more famous father.

More fundamentally, Roosevelt made an even deeper argument for his own conservatism: He argued that he was innovating to save the democratic capitalist system from itself — and from fascism on the right or communism on the left. But he was saving the system in the name of liberal goals, as exemplified in his “Four Freedoms” speech. Which helps explain why Norman Thomas — who was a socialist, not a communist — had much more in common with Roosevelt than with those who hated him, despite Thomas’ reluctance to go to war.

In short, the politics were complicated — as was the wide net that Richman used to try to capture his subject:

The Old Right includes several identifiable strands: “progressive” isolationists (such as Senator William Borah and John T. Flynn), Republican “conservative” isolationists (such as Robert Taft), libertarian and individualist iconoclasts regarded as leftist radicals in the 1920s (Mencken and Albert Jay Nock), conservative Democrats (such as Senator Bennett Champ Clark), World War I revisionists with a social democratic background (such as Harry Elmer Barnes), social democratic opponents of Roosevelt’s foreign policy (such as Charles Beard), a trio of individualist women writers (Ayn Rand, Rose Wilder Lane and Isabel Paterson), a group of free-market liberal economists and journalists (such as Frank Chodorov, Caret Garrett, Leonard Read, F.A. Harper and no doubt others), and some individual members who defy classification.

Richman didn’t try to show that all these people belonged together in any sort of coherent manner. But in a broad sense, he was correct that whenever dramatic historical changes happen, old alliances and allegiances become scrambled. That certainly happened in the wake of the Great Depression, not just in America but throughout the world. It’s happening again, right now.

And Richman went on to say that while the old right was diverse and unsystematic, its adherents knew “what they didn’t like,” which sounds a lot like the incoherent coalition that supports Donald Trump right now.

In another way, however, the 20th-century old right and the 21st-century alt-right are directly opposed: While the old right appropriated the legacy of Thomas Jefferson, portraying FDR as a would-be strongman, the alt-right just loves Trump’s strongman shtick. In that sense, libertarian heroes like Ron and Rand Paul, with their isolationism and anti-federalism, are much more orthodox descendants of the old right creed.

Rand’s effort to expand his father’s brand went nowhere this election cycle, and he is now backing Trump, however reluctantly. (Whereas Ron Paul recently hinted that he may support Jill Stein of the Green Party.)

To follow through on this point — how much libertarians like the Pauls align with the old right, while Trump does not — consider the following:

The laissez-faire wing pushed its philosophy into areas where “conservatives” preferred not to see it applied, for example, free trade and free migration. V. Orval Watts, writing in Chodorov’s “Freeman,” called for legalization of trade with the Soviet Union. Rejecting embargoes and government-subsidized trade, Watts, an author associated with the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), argued that free trade in goods would have an inevitable by-product, the export of American ideas.

Similarly, two other writers associated with Leonard Read, Oscar W. Cooley and Paul Poirot, called for a policy of free immigration. They regarded the freedom to come to America as merely an application of the founding ideals of the republic.

In short, they were far closer to Khizr Khan than to Donald Trump. And when it came to the supposed difficulty of assimilation, Cooley and Poirot (who are quoted by Richman) almost comically waved it away:

The assimilation of a foreign-born person is accomplished when the immigrant willingly comes to America, paying his own way not only to get here but also after he arrives, and peacefully submitting to the laws and customs of his newly adopted country.

What this diametrical opposition between the pro-immigration old right and the rabidly anti-immigration alt-right suggests — to re-emphasize an earlier point — is that what matters most in a given incarnation of the conservative movement is not some set of timeless principles but the nature of the immediate perceived threat.

One of the most helpful aspects of Richman’s account is the clarity it provided about how the old right lost the struggle for dominance within the conservative movement. At Vox, Dylan Matthews wrote that “the two defining moments that led to paleocon decline were the defeat of arch-conservative hero Robert A. Taft in the 1952 Republican primary campaign and the suppression of the conspiratorial John Birch Society by William F. Buckley and the National Review in the early 1960s.

That’s a neat encapsulation of the conventional historical account. But Richman provided a much more fine-grained discussion of how the old right’s philosophical concerns about individual liberty were first gradually and then forcefully shoved aside as the material threat of Soviet power came to overshadow everything else — at least in the minds of Buckley and his associates, who cemented their influence with the founding of the National Review.

What does all this mean in 2016? It means that “true conservatism” is dead because it was never really alive in the first place. It was a convenient fiction, nothing more. The expected defeat of Donald Trump will not put an end to the forces that made him possible and still less to those that seemed to make him necessary.

As Richman described, even into the mid-1950s there were old right figures who thought it was more dangerous to fight against Soviet Communism than to be conquered by it, but their power evaporated almost in mid sentence. What had once made perfect sense, at least in some quarters, now seemed ludicrous. We are almost certainly standing on the cusp of another such transformation in American conservative politics, regardless of what happens in November.