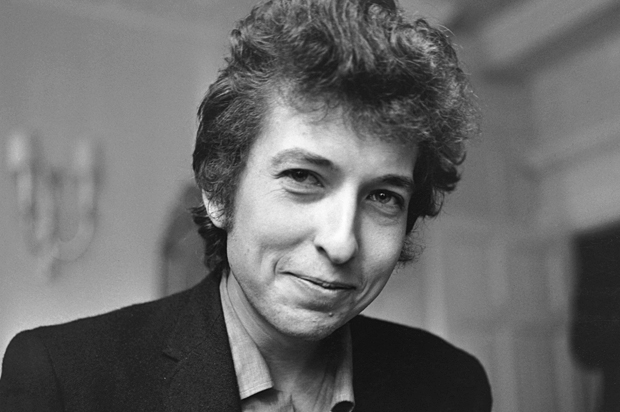

Well, this is complicated. Even if you love Bob Dylan’s music — as I do — there are several good reasons he should not get the Nobel Prize for literature.

Many Americans grumble when the award goes to a non-Anglophone writer they’ve not heard of and even more when it’s a writer whose work is not widely available in English. Who is this obscure poet (even worse) from this country that barely matters to me? But American readers know writers like Wisława Szymborska, Orhan Pamuk and Tomas Tranströmer — and are able to find their excellent work in bookstores — partly because of their Nobel wins. Plenty of readers, amazingly enough, didn’t know the masterful Canadian short story writer Alice Munro until she won.

Even reasonably informed Americans like yours truly are happy for this. So then what does an award to Dylan do to expand our sense of literature and the sometimes overlooked places where we can find it?

And most of Dylan’s lyrics don’t stand up terribly well as poetry: They sound great when he sings them, thanks to his gift for phrasing, but they die on the page. Slate’s Stephen Metcalf makes a well-argued case, which I am at least partially sympathetic to, that his songs aren’t really poetry at all. (At the very least, Metcalf is right that Richard Wilbur is many times the poet Dylan is.)

So is Dylan getting the award for his memoir, “Chronicles, Volume 1?” As excellent as that book is, is it really that much better than, say, Patti Smith’s equivalent, “Just Kids?”

Finally, awards of any kind that go to someone who is already vastly celebrated are far less effective and just than awards that tell us about someone working in any genre whom we don’t already know about — a person who might need and deserve the money or the prestige. Giving another Pulitzer to Philip Roth (who has been rumored as a potential Nobel contender for years) or Oscar to Spielberg has a winner-take-all effect: Why not recognize a genius who is not already covered in garlands?

But here’s where things get more ambiguous.

Some of the bitterness around Dylan’s Nobel comes from the fact that he’s primarily a musician. “If the Nobel Committees can give a peace prize to Henry Kissinger then it can give a literature prize to a man who hasn’t written any literature,” Tim Stanley wrote in Britain’s Telegraph. “This is the Nobel Prize for Literature. Not Sweden’s Got Talent.”

Some are wondering if the award will now go next to Chuck Berry, Kanye West and others.

But at the beginning of the Western tradition — the creation of the poetry and drama of ancient Greece — music was a key part of literature: It was the strumming of the lyre that gave us the term “lyric poetry.” I’m not sure music should weigh nearly as heavily as words in the assessment of a writer’s heft, but it should certainly not count against.

And here’s the other thing: It’s not like Dylan is just another musician or just another songwriter. He’s done more for language of Anglo-American popular culture than perhaps any figure ever. Elvis Presley, Berry and James Brown may have had as much musical influence as Dylan, but the seriousness of lyrics in the rock tradition came heavily from the man born Robert Zimmerman.

Needless to say, Dylan did not wholly invent the tradition of artful song lyrics: He took bits from the blues, from the English and Scottish Child Ballads, from T.S. Eliot and French Symbolist poets, from Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams and a wide range of other influences, and combined them in a way nobody had dreamed of before.

And while some days I would prefer songs of Leonard Cohen, Richard Thompson, Townes Van Zandt or Lucinda Williams in the singer-songwriter category, all four were profoundly shaped by Dylan, and he created the market identity that made their careers possible.

The music that unites the U.S. with the rest of the world, that elderly members of the Silent Generation and small children love in common, is not, generally, Dylan’s but the Beatles’. But that band would have been much less interesting without his example.

In January 1964, George Harrison bought “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” with songs like “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” at a record store in Paris. Almost immediately, Dylan’s mark began to show up in the band’s work, from the immediate (mostly musical rather than lyrical) impact of “I Should Have Known Better” to the deeper influence on the “Beatles for Sale,” “Help!” and “Rubber Soul” albums. Not to mention just about everything the group did after.

We would probably not have the mighty Byrds, California’s Laurel Canyon movement, the mature phase of the Beach Boys, Bruce Springsteen or the alt-country movement (much of which draws roots from The Band, Dylan’s old backup group). Just about all of these bands brought a greater lyrical sophistication to popular music.

I’m less convinced than most fans by the supposed revival of Dylan’s genius since 1997’s “Time Out of Mind.” And lately as a live act, he is not the equal of many of his generational peers, including those he will perform with this weekend at the “Oldchella” Desert Trip festival.

His most restlessly innovative, emotionally committed and musically inventive period remains the era from 1962 to 1976, from the releases of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” to “Desire,” and with a particularly spike around the pre- and immediate post-motorcycle crash era. (That means “Highway 61 Revisited, “Blonde on Blonde,” the stark “John Wesley Harding” and the raw, soulful recordings that came to be known as “The Basement Tapes.”)

While there’s a sag in the early ’70s, this is as strong a run as any rock musician has ever had, and better than the run of many great writers, including Nobel winners. This doesn’t mean that the Swedish academy is dumbing down or opening the door to Britney Spears or overlooking its central goal. It means it’s paying attention and recognizing a literary genius many times over.