This article originally appeared on Capital & Main.

Brett Bymaster, a Silicon Valley electrical engineer, was optimistic when Rocketship Education, a non-profit charter school chain, began building its flagship Mateo Sheedy elementary school next to his San Jose home in 2007. He and his family lived in a lower-income community, so he figured the new approach could help local kids. “I didn’t know anything about charter schools, so I thought it was a good thing,” he says.

But the more he learned about Rocketship and charter schools, which receive government funding but operate independently of local school boards, the more concerned he became. He was struck by the school’s cramped quarters: over 600 students on a 1-acre campus, compared to the 9.2 acres per 450 students recommended for elementary schools by the California Department of Education. All those students meant big classes; last year Mateo Sheedy had one teacher for every 34 students, more than the maximum allowed for traditional elementary schools under state law.

The teacher deficit seemed to be compensated for with screen time: Thanks to its so-called “blended learning” approach, Rocketship kindergarteners were spending 80 to 90 minutes a day in front of computers in a school learning lab, nearly the daily maximum screen time recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. And when the kids weren’t in front of computers, they seemed to be getting disciplined throughout their extra-long school days. Bymaster says he’d constantly see teachers yelling at students. “It’s a military-style environment,” notes Bymaster, who spearheaded a 2013 lawsuit that caused Rocketship to scrap one of its planned San Jose schools. “It’s really a kill-and-drill kind of school.”

Rocketship, which now operates 16 schools in the Bay Area as well as Tennessee, Wisconsin and Washington, D.C., has been praised for using technological innovation to improve test scores and other education measures for its largely low-income and Hispanic student bodies. But its stringent, tech-heavy approach has drawn criticism, while some of those lauded test scores have started to dip. (A Rocketship spokesperson did not respond to e-mailed questions by press time, but the operation published a lengthy defense of its program after an NPR feature detailed Rocketship criticisms this summer.)

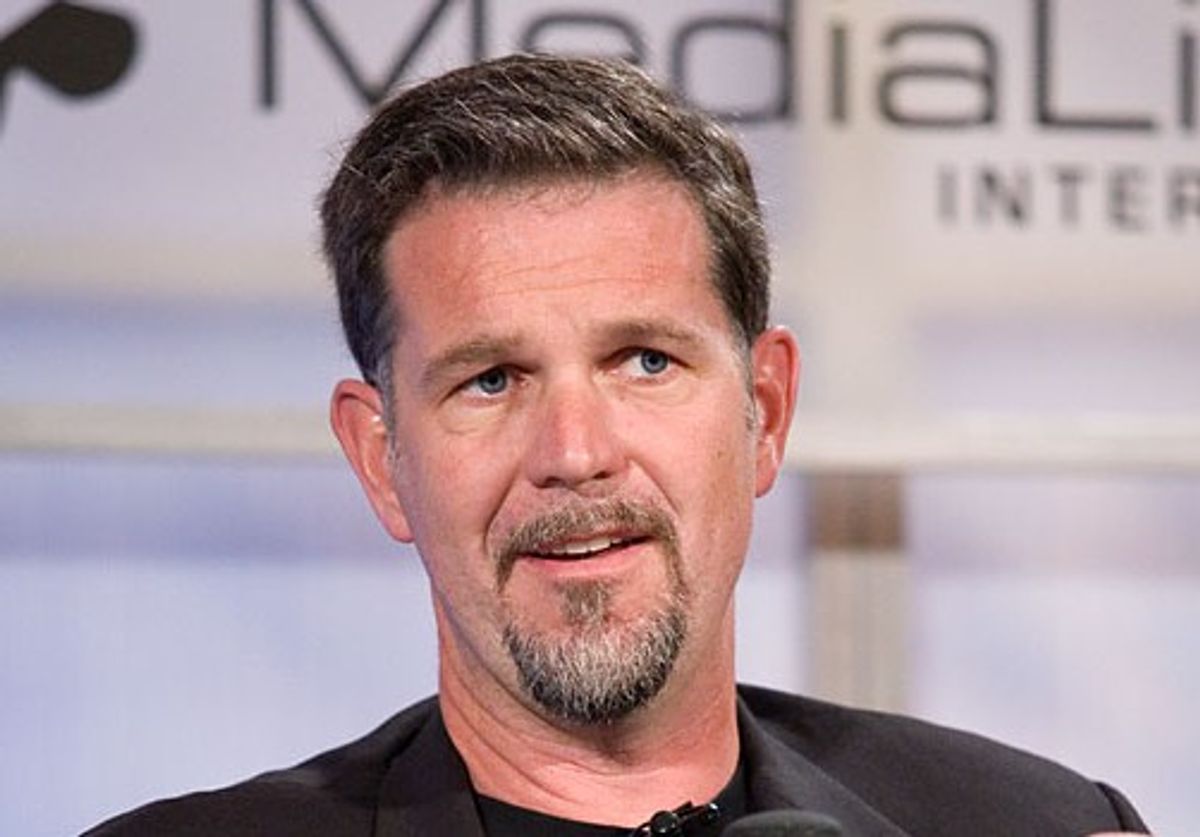

Concerns about Rocketship extend to its most prominent backer: Reed Hastings, CEO of Netflix, who has heavily supported the charter chain, including a $2 million donation last year. Rocketship is far from Hastings’ only charter school effort. The one-time California Board of Education president, who declined to be interviewed for this story, helped launch the powerful EdVoice pro-charter lobbying group and so far this election season has donated more than $3.7 million to the California Charter Schools Association (CCSA)’s political action committee. But critics worry that the sort of technologies and efficiencies Hastings used to build his Silicon Valley empire and is now applying to education reform might not work for the nation’s schoolchildren.

These concerns were amplified when Hastings, at a 2014 CCSA meeting, asserted that public schools are hobbled by having elected schoolboards.

“Let’s think large-scale,” says Bymaster, who broke the story about Hastings’ school board comments on his StopRocketship.com blog. “You have someone who is contributing millions and millions of dollars to local and statewide political races and who was the former president of the state school board whose stated goal is to end democracy in education. That is deeply disturbing.”

Hastings, who growing up attended public and private schools, first became interested in education after college. He ditched his plan to serve in the Marine Corps and joined the Peace Corps, teaching high school math in Swaziland before returning to the States and earning his master’s degree in computer science from Stanford University. “I’m not good at following orders,” said Hastings in a 2015 EducationNext profile. “There were no rules at all [in the Peace Corps]. Just use your initiative.”

After the success of his first start-up, the debugging program maker Pure Software, made him a multimillionaire in 1995, Hastings decided to use some of his wealth to tackle the problems he saw in the nation’s schools. “I started… trying to figure out why our education is lagging when our technology is increasing at great rates and there’s great innovation in so many other areas—health care, biotech, information technology, moviemaking,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “Why not education?”

His efforts began in 1998, when he and Don Shalvey, who’d helped launch California’s first charter school, set their sights on abolishing California’s 100-charter school cap. According to The Founders, a new e-book about the early years of the charter school movement published by the pro-charter news organization The 74, Hastings personally gathered petitions at supermarkets for a ballot initiative to lift the restriction. Instead of passing that initiative, Hastings and Shalvey convinced the state Legislature to act. “Not only did a bill pass that essentially green-lighted an unlimited number of charter schools…but the bill included a provision barely noticed at the time, certainly not by the unions: A single board of directors could oversee multiple charters,” notes The Founders. That provision would allow Hastings and Shalvey, who is now deputy director of education at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to launch Aspire Public Schools, the nation’s first charter network, which now operates 40 schools in California and Tennessee.

Hastings had less success when Democratic Governor Gray Davis named him to the state Board of Education in 2000. While president of the board, he aggressively pushed for English-language instruction for immigrant students, adopting a policy that limited federal funding for elementary schools that weren’t teaching at least 2 ½ hours in English every day. That rule, later overturned, was part of what education observers say was a lengthy dismantling of California’s bilingual education programs. Hasting’s stance on the matter caused Democratic legislators to block his reappointment in 2004, despite the fact that he was a key Democratic donor. “Just because [Hastings] and right-wing Republicans thought it was a good idea to force immigrant children to speak only English in school, he gets to derail bilingual education for a decade?” says Karen Wolfe, a California parent and founder of PSconnect, a community group that advocates for traditional public schools. “That’s not disruption. That’s destruction.”

The fact that California Charter Academy, one of the country’s largest charter school operators, collapsed and left 6,000 California students without a school during his board tenure did little to sway Hastings’ enthusiasm for publicly financed yet privately run schools. Along with helping to fund the Rocketship and Aspire charter programs, he’s served on the boards of the California Charter Schools Association and the KIPP Foundation, the largest network of charter schools in the country. And much of Hastings’ school reform efforts have focused on technological solutions. He helped launch NewSchools Venture Fund, which has invested $250 million in education entrepreneurs and “ed tech” products. He’s also been a major backer of DreamBox Learning, which develops the math software used in Rocketship schools, and the Khan Academy, an online teaching video clearinghouse.

But so far, the outcomes of many of these ed tech ventures have been mixed. Khan Academy has been criticized for including fundamental math errors in some of their instructional videos. And while DreamBox recently championed a Harvard University study that found that use of its math software was associated with test achievement gains in grades 3 through 5, the study itselfnoted it could not be ruled out that the gains were “due to student motivation or teacher effectiveness, rather than to the availability of the software.” What’s more, the user data collected by programs developed at Khan Academy, DreamBox and other companies are fueling concerns over student privacy.

More broadly, education experts are worried about the impact of minimally staffed, call center-like computer learning labs on the nation’s students and teachers, especially as these approaches become more commonplace in the name of cost savings and innovation. (In a 2012 Washington Post article, former Rocketship CEO John Danner noted that “Rocketeers” could eventually spend 50 percent of their school day in front of computers.)

“The younger a kid is, the more critically important it is that they construct their own knowledge and figure out how the universe works, and they literally cannot get that from a computer screen,” says Launa Hall, a former Virginia elementary school teacher who now writes and consults on education issues. “Reed Hastings had an opportunity to have a rich and nuanced education and he talks about how the Peace Corps were so awesome because there were no rules. So his heart might be in the right place, but he might have forgotten his own roots in how he came to value education.”

Hastings’ preferred school reforms, such as heavy use of streaming technologies and data collection, resemble the way he built Netflix. And critics say that could be part of the problem. Netflix’s workplace culture, which involves employees taking as much vacation as they like and choosing their own stock-to-cash ratios, has been hailed as groundbreaking. But some say Netflix, like many Silicon Valley companies, offers these perks not because it wants to reform labor conditions across the board, but because it’s a smart business move, allowing it to attract better candidates for top positions. As noted in a widely shared PowerPoint presentation on Netflix company culture that Hastings made public in 2009, “We’re like a pro sports team, not a kid’s recreational team. Netflix leaders hire, develop and cut smartly, so we have stars in every position.”

It’s why when Netflix became the first major U.S. company to offer unlimited paid family leave for both male and female employees, it was criticized for extending the policy only to its white-collar employees, not blue-collar workers in charge of customer service and DVDs. And while Microsoft has required that many of its contractors and vendors provide their workers with sick days and vacation time and Google has demanded that its shuttle bus contractors pay better wages, so far Netflix has ignored calls for improved working conditions for its contract workers, says Derecka Mehrens, co-founder of Silicon Valley Rising, a campaign to raise pay and create affordable housing for low-wage workers in the tech industry.

Mehrens sees a similar class bias in Hastings’ approach to public education. “We see profound consequences, both political and economic, when technology industry leaders take action from a position of privilege and isolation from the very communities they desire to help,” she says. “When tech industry leaders like Reed Hastings call for an elimination of school boards or for more privatization of public schools, they block low-income people from using the one instrument that the powerful can’t ignore – their vote.”

Hastings’ end goal for California appears to be the near-total replacement of traditional public schools with charter schools. In his 2014 speech where he discussed abolishing elected school boards, Hastings pointed to New Orleans – whose school system was largely taken over by the State of Louisiana after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina and converted to the country’s first predominantly charter public school system – as a model:

“So what we have to do is to work with school districts to grow steadily, and the work ahead is really hard because we’re at eight percent of students [in charters] in California, whereas in New Orleans they’re at 90 percent, so we have a lot of catchup to do… So what we have to do is continue to grow and grow… It’s going to take 20-30 years to get to 90 percent of charter kids.”

When Hastings announced a new $100 million Hastings Fund for education grants earlier this year, he named as CEO Neerav Kingsland, who previously helmed New Schools for New Orleans, a nonprofit that helps fund and support New Orleans’ charters. “It’s about backing great educators who want to scale great schools,” says Kingsland of the new venture. “There’s a huge focus on quality education, focusing on doing what needs to be done to serve great students.” He adds that the Hastings Fund is not just about backing charters: “The neighborhood school is this idealistic 1950s idea, but for a lot of people enrollment in neighborhood schools is a sentence into educational disenfranchisement. Maybe charters are not the right answer and there are other ways of getting around it, but to say that what we have is okay is out of touch at best, malevolent at worst.”

By some measures, what Kingsland and others accomplished with New Orleans’ charter experiment has been a success. Over the past half-decade, the city boasted the greatest improvement in test scores of any urban school system ever. But the program still has a long way to go: In 2014, just 57 percent of students in grades three through eight scored a passing grade on state accountability tests, significantly below statewide and nationwide averages. “I am really open that as we built the system, there were mistakes, there were bad apples. But by the end, we figured out how to empower educators and have government accountability,” says Kingsland. “I would say that there were legitimate concerns that we are just not good enough yet, and I hope we get there. But I think it would be wrong to say that things haven’t gotten a lot better.”

Others vehemently disagree with that characterization. “You can say until you’re blue in the face that this should be a national model, but this is one of the worst-performing districts in one of the worst-performing states,” Julian Vasquez Heilig, an education professor at California State Sacramento, told In These Times last summer.

Beyond test scores, New Orleans’ charter system has contributed to citywide upheaval that’s led to a major decrease in diversityof a once largely African American teaching force, struggles with integrating arts education and English language acquisition (ELA) into charter programs and a class-action lawsuit alleging schools were failing students with special needs. A 2015 study found that 18 percent of the city’s youth ages 16 to 24 were unemployed and out of school, a figure that’s markedly higher than the national average and could be contributing to the region’s struggles with child poverty and crime.

“Whatever perceived benefits that are out here, they are outweighed by the harms that have been done, especially by those children with disabilities and the 26,000 kids on the streets,” says New Orleans education advocate and charter school critic Karran Harper Royal. “For those people who came into town after something as devastating as Katrina and turned our school system upside down and took away arts and everything else that makes you a well-rounded student, that did a lot of harm to us as a people.”

Earlier this year the Louisiana Legislature voted to return partial oversight of city schools to local school boards, a move even charter advocates like Kingsland supported. The development is at odds with Hastings’ contention that locally elected school boards are part of the problem.

“This is a part of our democracy,” says Vernon Billy, executive director and CEO of the California School Boards Association. “Whether it’s electing school boards or city council members or congressional representatives, that is our process in this country. It may not be as timely as some people would like, but when you look at the fact that roughly 90 percent of our children go to public schools nationwide and in California as well, and this country is ultimately one of the most successful countries in the world, we must be doing something right.”

Even as supporters continue to pour money into charter schools, critics have succeeded in raising fundamental questions about the charter model, leading groups like the NAACP to call for a moratorium on the expansion of privately managed charters schools. In California, test scores have fallen sharply at some charter schools, including Rocketship and Aspire campuses, while demands for greater charter accountability and oversight have increased.

Undeterred, Hastings and other school reform-minded tech billionaires want to inject the start-up mentality into the country’s schools, using high-tech solutions to replace human labor and disrupting longtime management and oversight approaches in the name of efficiency. But to Bymaster in San Jose, that’s not the right approach. After all, roughly half of all start-ups fail. What happens to the children who get caught in those failures, like the students left without a school when California Charter Academy folded, like the tens of thousands of kids roaming New Orleans streets?

“I have been through several successful Silicon Valley start-ups. I am as techy as they come,” says Bymaster. “But ultimately the problems in our schools are people problems. Technology doesn’t solve people problems. People solve people problems.”

Shares