Lost in the mountains of Clinton campaign chair John Podesta’s stolen emails and Republican candidate Donald Trump’s cavalcade of palaver, one of the more interesting long-term trends in politics has been taking place: American libertarianism is slowly splitting apart.

Given the small number of people who can reasonably be classified as libertarian (just 15 percent of Americans, according to a 2013 PRRI poll), it’s understandable that few political observers are paying much attention. That said, many observers have noticed that in several states, public opinion polls have indicated that the Libertarian Party’s presidential ticket appears to be drawing more support away from Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton than it is from Trump.

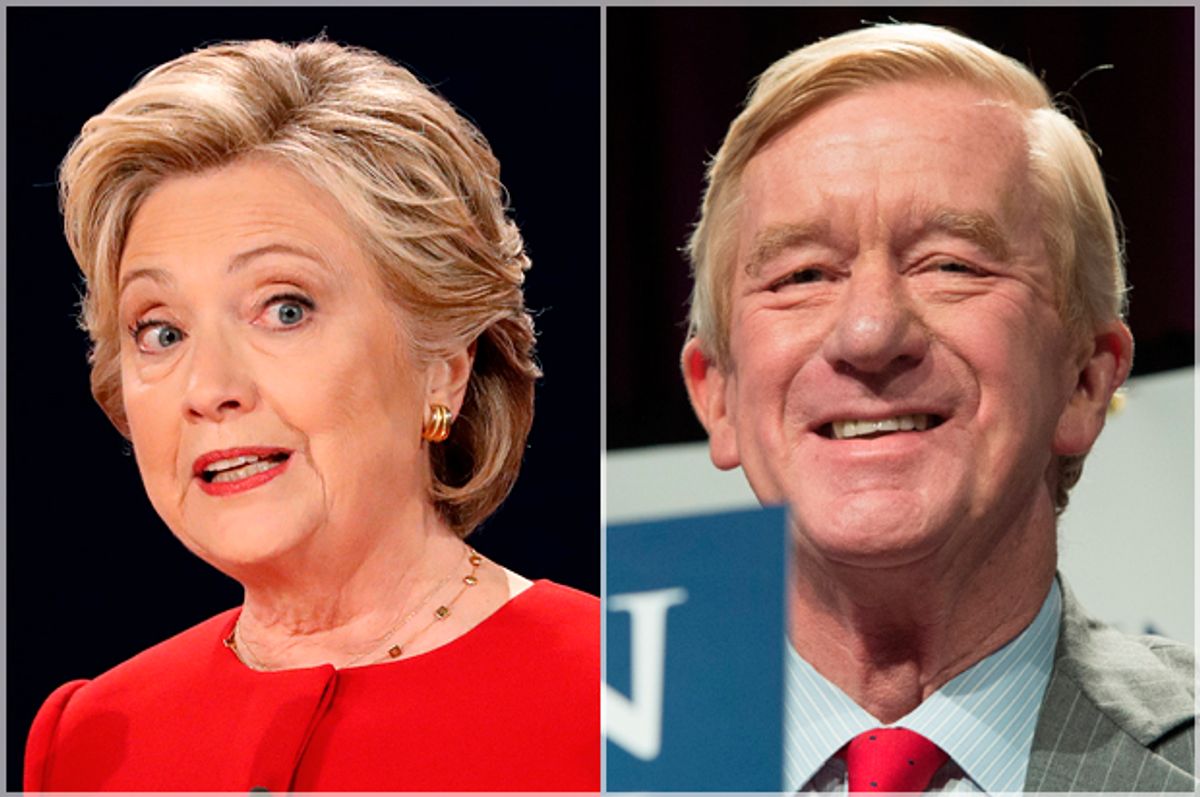

This makes sense in a way because the libertarianism of the party's presidential nominee Gary Johnson and his running mate William Weld is quite different from that of Ron Paul, the man who until recently had been the political embodiment of the movement. Ironically, it’s been the candidacy of Republican Donald Trump that has accelerated this bifurcation.

One person who has been watching the situation unfold is MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, who posed a series of interesting questions to Weld on her show last night. Maddow’s interview with the twice-elected former governor of Massachusetts was quite fascinating.

In the discussion, Weld said he recognized a “big difference” between Clinton and Trump, one that frightened him.

“I’ve been at some pains to say that I fear for the country if Mr. Trump should be elected,” Weld said. “It’s a candidacy without any parallel that I can recall. It’s content free and very much given to stirring up ambient resentment and even hatred. And I think it would be a threat to the conduct of our foreign policy and our position in the world at large.”

Weld also strongly commended the integrity and competence of Clinton, saying that he considered her “a person of high moral character, a reliable person and an honest person.”

Having said all that, however, Weld stopped short of recommending that people living in swing states vote for Clinton, despite repeated prodding from Maddow.

“I can’t imagine that you wouldn’t tell a person in North Carolina or Ohio to vote for Hillary Clinton if the choice they were making was between giving the Libertarian Party 5 percent or potentially electing Donald Trump,” Maddow wondered aloud.

She probably should have known better, however. Asking a candidate to tell voters to choose a competitor, even a friend, is like asking a cat to turn down fish.

Weld stopped short of her request but continued praising the former secretary of state:

“Well I’m here vouching for Mrs. Clinton and I think it’s high time somebody did and I’m doing it based on my personal experience with her and I think she deserves to have people vouch for her other than members of the Democratic National Committee so I’m here to do that.”

It’s possible that Weld could simply be angling for a spot in a future Clinton administration — he was nominated to be former president Bill Clinton's ambassador to Mexico — but there’s something more to it than that. Libertarianism is undergoing its own split as moderate Republicans fleeing their party in disgust are dislodging the cranks and racists who previously had coalesced around Ron Paul but now are gravitating toward Trump and the alt-right.

But even laissez-faire economics, the core of the "liberty" political program, are also coming under challenge as well as evidenced by the recent creation of two offshoots that have taken root from libertarianism’s largest policy organizations, the Cato Institute and the Heartland Institute. These two groups, the Niskanen Center and the R Street Institute respectively, have been promoting a form of libertarianism that's more focused on competence and choice rather than the right's long-desired goal to drown the government in the bathtub.

Walter Olson, one of Cato’s less doctrinaire scholars, summed up the dynamic of this new form of libertarianism in an August piece for Reason magazine:

In one communication after another, the Johnson-Weld campaign strikes a theme seldom associated with past libertarian campaigns in the US: moderation. It is the "sane" choice, the "responsible" and "adult" ticket, the ones happy to work with the best people and ideas from both parties, campaigning not on fear and anger but on a positive message of problem-solving. A recent Johnson video contrasts a bickering, shouty Trump and Clinton with the cool-and-collected libertarian alternative.

Olson continued:

As a more or less lifelong libertarian I'm still getting used to the idea of its being the middle position in an election, the oasis of sanity, the haven from extremism. But win or lose, I don't think this campaign will be the last of what I've come to call libertarian centrism. That position has a logic of its own, as well as a considerable historical pedigree.

And he further added:

In Europe liberal parties, often seen as the nearest analogue of libertarian, are often perceived in just this way as occupying centrist/middle positions between labor or revolutionary parties on the left and blood-and-soil or religious parties on the right. European liberal tendencies vary but often they're secular, business oriented, pro-trade, modern, internationalist but not militarist, and interested in meliorist reform rather than street politics or national crusades. Sound familiar?

So on general principle we shouldn't assume that if you squeeze the libertarians out of the GOP coalition, they'll pop out on the far right. (Or far left.) They might pop out in the center instead, as Bill Weld clearly has and Gary Johnson shows signs of doing as well.

As the Republican Party and conventional conservatism continue tearing themselves apart in the bubble of right-wing media, it’s starting to seem possible that the people who would actually rather accomplish something may be opting out completely. The Democratic Party will soon have a lot more members and if Weld has his way, so will the Libertarians.

Shares