This article originally appeared on Climate Central.

“We do see some pretty high tides, even without the full moon,” said JB Workman, a golf course employee who moved into an increasingly flood-prone neighborhood in Georgia several years ago. “This past weekend the flooding was like I've never seen during my time here — way worse, and dangerous.”

In recent years, America has been playing an outsized role in efforts to slow global warming, which would ease future sea level rise, though nothing could completely halt the problem now. That leading role could now be in jeopardy as Trump has called climate change a “hoax” and said during his campaign that he would withdraw America from efforts at the United Nations to address climate change.

Domestically, the federal government plays key roles in protecting coastal communities from floods, a job made more challenging as seas rise. That role may also be jeopardized, given promises Trump and Republicans in Congress made to slash federal spending.

A large full moon called a “supermoon” pulled tides higher from Sunday until Wednesday, triggering the latest episode of sweeping coastal flooding. Such floods are most common in the spring and the fall. As high tides in the spring and fall have been causing worsening floods, people have taken to calling them “king tides.”Every year nationwide, sea level rise caused by global warming is directly responsible for hundreds of high tide floods like those in Workman’s neighborhood. Coastal planners are grappling with the worsening problem, which is most pronounced along the East and Gulf coasts, where sea level rise has been fastest and where land is sinking and eroding away.

Out of 15 floods caused by high tides at locations monitored with tide gauges, a Climate Central analysis of federal data found 12 were driven by the effects of greenhouse gas pollution on sea levels.

As sea level rise has accelerated during the last half century, high tide flooding has become routine in some places and will continue to get worse. Climate change pushed high tide waters above local flood levels for three-quarters of the thousands of tidal floods in America from 2005 to 2014, analysis by Climate Central in February showed. That was up from less than half in the 1950s.

High tide floods are rarely deadly unless they coincide with a powerful storm. These minor floods block roads, including the only freeway connecting Tybee Island in Georgia from the mainland. They can swamp basements and storefronts, which occurs regularly in parts of Maryland. And the salt they bring can kill forests and affect farmland.

Economic impacts of these floods can be difficult to assess. They include costs to retailers that can’t open their doors on some days and damage caused by floods to cars and buildings. Fixes are expensive: Infrastructure improvements needed to ease regular flooding in Norfolk, Va., have been estimated $1 billion.

Aside from nuisance flooding, sea level rise causes property damage and jeopardizes lives by pushing storm surges higher — including the deadly pulse of water wrought by Hurricane Sandy. Global warming also means bigger storms and heavier rain.

Dangers of rising seas are felt worldwide, from Bangladesh to India, Russia, Canada and the United Kingdom. Leaders from China and Brazil have implored Trump to abandon his apparent resistance to a global climate treaty. After the election, a French politician suggested Europe prepare to launch a trade war over the climate policies Trump espoused on the campaign trail.

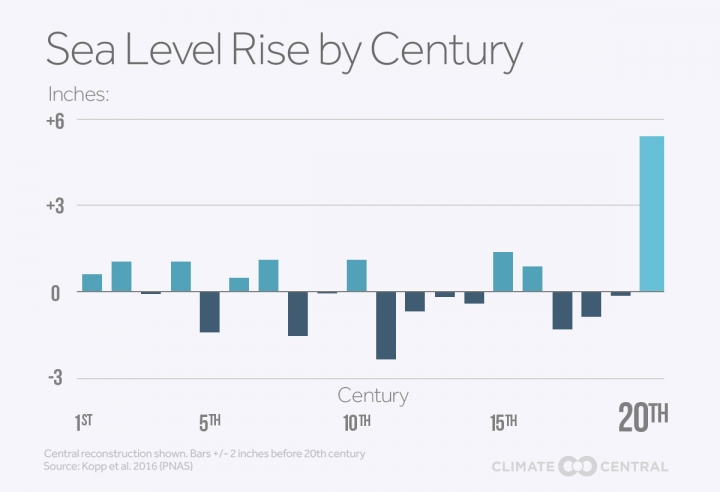

Seas rose about half a foot during the 20th century, mostly because of global warming, and they’re rising at an accelerating rate. “We know it will rise; we know it will accelerate,” said Rutgers University professor Ben Horton. “The exact magnitude is unknown.”

If the goals of the new climate treaty are met, a rapid global transition from fossil fuel energy to clean alternatives and a quick halt to deforestation would limit sea level rise this century to another foot or two — worsening and triggering floods the world over. Failing to address global warming could see seas rise more than twice that quickly. (Seas would rise far faster than that if ice sheets at the north and south poles collapse.)

That difference is “stark,” Horton said, with some coastal regions that could potentially be adapted to rising seas becoming “non-adaptable” if global warming is not urgently addressed.

The potential costs of higher sea levels are staggering — in terms of jeopardized property and infrastructure, the costs of adapting to the changes underway and human lives and suffering.

Research published in 2014 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences projected that global damages from sea level rise could reach $19 trillion a year by 2100 — which would be more than America’s GDP last year.

As sea level rise accelerates, “we see more impacts along our shorelines,” said Jessica Grannis, who researches climate adaptation at the Georgetown Climate Center. “The level of effort is going to have to increase as well, to make sure that we don’t have people and property in harm’s way.”

Adapting to rising seas can involve abandoning some infrastructure and neighborhoods. It can involve figuring out how to live with regular floods, such as by raising houses on stilts, or by building ground floors that can withstand water damage. It can also involve building wetlands and concrete walls to keep water away from buildings and roads.

The role of federal agencies in helping local communities adapt to sea level rise is “not primary,” Grannis said — but it is “huge.”

“They provide a lot of the data and technical analysis that the state and local governments are relying on,” Grannis said. “They provide a lot of the tools they’re using. They provide a lot of the funding that they’re relying on to not only plan but also to implement projects.”

That federal support is already falling behind the needs of America’s coastlines, and there are fears that it will fall further still under Republican control of the White House and Congress.

A federal report produced following Hurricane Sandy identified more than $2 billion in Army Corps projects that had been authorized in the region by Congress but that remained unfunded.

“The biggest challenge facing the nation is relative to funding — and the political will to provide that funding,” said Michael Walther, vice president at coastal engineering and consulting firm Coastal Tech. “The policies of President-elect Trump to reduce taxes would point to a further reduction in meeting these needs.”

Coastal infrastructure planned and underway in New York and New Jersey was spurred by the devastating impacts of Hurricane Sandy’s storm surge, which in 2012 destroyed neighborhoods in New Jersey and inundated streets of New York with two to three feet of water.

In New York, the Army Corps of Engineers is proposing a multibillion-dollar storm surge barrier at the Rockaways to protect the city from the dual effects of storms and rising seas. In New Jersey, the federal government has been providing the bulk of the money needed for a seawall and other projects in Atlantic City, which flooded this week, because the city is broke following the failure of waterfront casinos — two of which bore Trump’s name.

The federal government is also a key source of funding and leadership for major coastal projects in other parts of the country. A master plan to protect Louisiana’s coastal lands from rising seas, erosion and other threats would require an estimated $50 billion to execute — and even that would not stem ongoing land losses. In California, plans to restore marshes to reduce flood risks around San Francisco Bay as seas rise are projected to cost $1.5 billion over 20 years.

Derek Brockbanks, executive director of the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association, said there’s a “quantifiable gap” between the value of federal coastal projects approved by Congress and the amount of funding appropriated for those projects.

“I’m trying to figure out this number, since I think it will be helpful if and when there’s a push for an infrastructure spending bill in the new year,” Brockbank said. “ASBPA anticipates some major changes with the new administration.”

Like other organizations based in Washington, the ASBPA, which lobbies lawmakers and officials to invest in coastal infrastructure and simplify federal permits and take other steps to protect coastal America, is trying to prepare for federal changes expected under Trump.

A main thrust for the organization under Trump will be pushing for more funding for the coasts — funding that could be hard to find, with Republicans controlling the White House and Congress. Then again, Trump appears to be planning to prioritize infrastructure spending under his presidency.

“Both candidates campaigned on the need for greater U.S. investment in infrastructure,” Brockbank said. “Now, post-election, we’ll work to hold the new administration to that commitment.”

As Americans have been grappling with the early effects of rising seas, President Obama had been leading global efforts to slow climate change. America and China jointly championed a new approach to climate diplomacy culminating in the Paris climate pact last year, under which nations make voluntary pledges to ease their impacts.

Trump’s election last week threw United Nations climate negotiations that are underway in Morocco into crisis. Those talks were designed to help hone the rules of a Paris agreement, which aims to limit temperature rise — and to slow the rise in sea levels.

For Tulane University geography professor Torbjörn Törnqvist, an expert on land losses along the Gulf Coast, the most important step Trump could take now to protect America’s coasts would be to join in the fight against global warming.

“There is one overwhelmingly dominant priority, namely honoring the Paris climate agreement and working toward further strengthening it,” Törnqvist said. “This trumps everything else.”

Shares