It’s the best news for Democrats in weeks: Partisan gerrymandering is on a collision course with the Supreme Court.

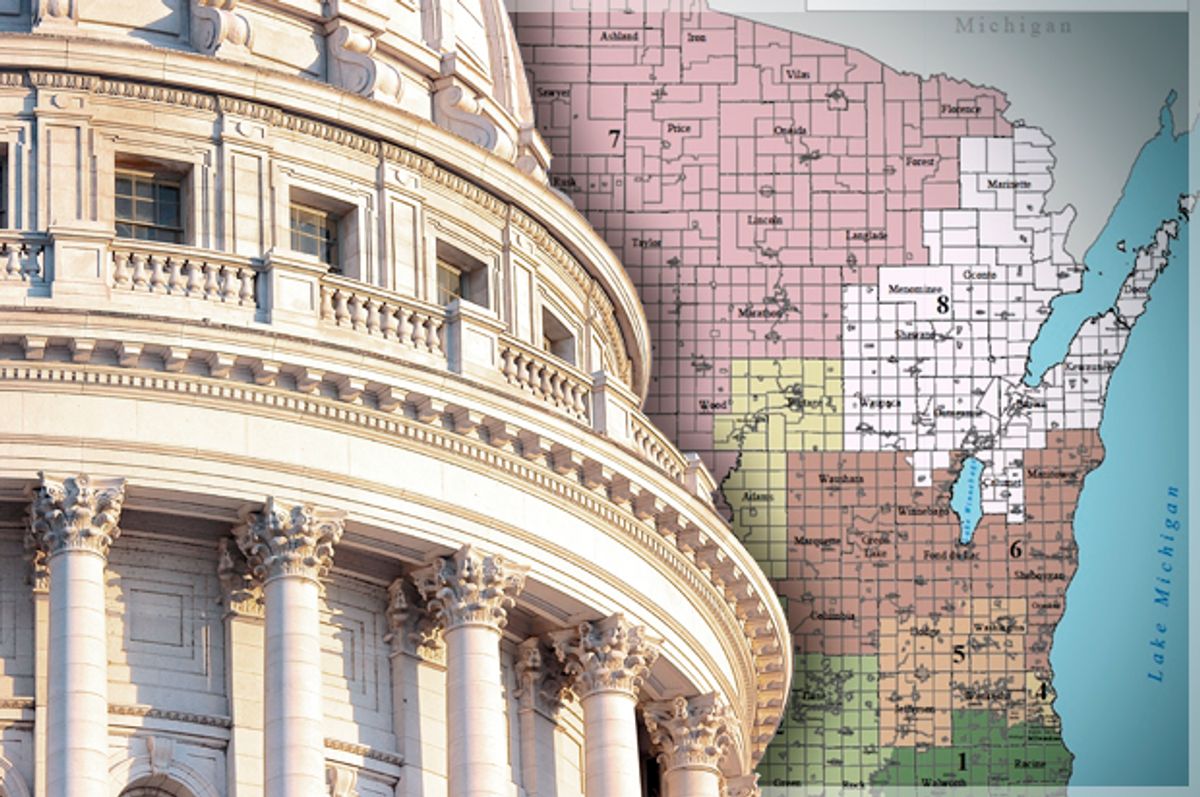

There’s a reason why Democrats routinely get more votes — whether at the state level or in six of the last seven presidential elections — but Republicans control all the power at the federal level, as well as 69 of 99 state legislative chambers. In the ruthless Republican redistricting that followed the 2010 census, GOP politicians drew themselves all but guaranteed majorities in state legislatures and Congress, insulating themselves from voters.

The plan was called the Redistricting Majority Project (or REDMAP for short) and that’s exactly what this devastating reinvention of the oldest political trick in the book — the gerrymander — produced.

But in a Monday ruling with far-reaching national implications, a panel of three U.S. district judges, in a 2-1 decision, had enough of this corrosively anti-democratic practice. He called Wisconsin’s state legislative maps an “unconstitutional political gerrymander” and systematically dismantled the zombie myth that even our elite media won’t let die. Extreme and highly targeted partisan gerrymandering — not geography — he ruled, explains why Republicans have “locked in” control even when they receive fewer votes.

“The evidence at trial establishes that” the goal of the GOP’s maps “was to secure the Republican Party’s control of the state legislature for the decennial period,” wrote Kenneth Ripple and Barbara Crabb, U.S. district judges.

This is not the first time that aggressive GOP maps drawn in 2011 have run afoul of the courts. Judges in Florida, Virginia and North Carolina cases have already found massive evidence of unlawful partisan intent and even conspiratorial shadow redistricting processes and have forced several districts to be redrawn.

Emails and draft maps revealed through the discovery process in all these cases have put the extreme GOP efforts to rig our democracy on full display. And yet, ever since the election, pundits and professors have repeatedly declared that the Republicans win legislative races because their votes are better distributed across states than Democrats, who tend to crowd and concentrate themselves in urban areas.

This analysis has dismissed reams of new political science studies that have explained how different and long-lasting the GOP gerrymander of 2010-11 will be. And it has ignored very public and honest explanations by Republicans of the electoral strategy that made this gerrymander possible – let alone the less public and much less honest private emails, algorithms and court transcripts that laid out the breathtaking depth and determination behind the GOP plans.

Judges Ripple and Crabb’s decision will prove harder to ignore, even for the smarty-pants head-in-sand brigade at The New York Times’ Upshot brigade, which dismissed the importance of partisan gerrymandering and pinned the Democrats’ problems on geography yet again just on Monday morning. It’s just the latest example of how the Times’ intellectually dishonest coverage has normalized the GOP’s radical actions and refused to grapple with the serious ways in which the 2010 and 2011 redistricting plan was a decennial power grab like any other in our history.

While the Times’ writers stare only at data, Judges Ripple and Crabb explored how these lines actually came to be — in a ruling that’s reads like Thomas Pynchon characters enacting a Jeffrey Archer political thriller — and laid out how this essential democratic practice became infected with partisan intent.

As the judges narrated the story, two Republican aides, locked in the “map room” at a GOP-aligned law firm across the street from Wisconsin’s capital, enlisted the help of a University of Oklahoma professor named Keith Ronald Gaddie and set about using devious calculations and powerful new mapmaking technology to craft unbeatable lines for their side for the next decade.

Ottman and Foltz created a partisan score based on election results from 2004 to 2010 and a cloud’s worth of exacting demographic detail. They sent that to Gaddie, deeply skilled essentially at providing academic cover for partisan gerrymandering. He tested their model against his own and ruled it the very best it could be.

When Ottman presented the maps to the Republican caucus, he highlighted the partisan impact: “The maps we pass will determine who’s here 10 years from now,” he said, adding, “We have an opportunity and an obligation to draw these maps that Republicans haven’t had in decades.”

The maps worked to the promised perfection. In the first election run on them, in 2012, Democratic assembly candidates earned more votes. Republicans won 60 of the 99 seats. For the Democrats to have a chance to win the majority in the chamber, the judges found, the party would need some 55 percent of the votes. That’s not natural distribution, he argued; it’s intentional and carefully crafter distribution aimed at unconstitutionally limiting the power of the vote.

“The evidence makes clear,” the court ruled, “that although Wisconsin’s natural political geography plays some role in the apportionment process, it simply does not explain adequately the sizeable disparate effect seen in 2012 and 2014.”

The plaintiffs who brought this case aimed it squarely at Justice Anthony Kennedy. Kennedy will remain the crucial vote on the Supreme Court once President-elect Donald Trump appoints and the GOP-controlled Senate confirms a ninth justice next year. And when the question of partisan gerrymandering last reached the court in the 2000s, Kennedy declared himself open to declaring it unconstitutional — something the court has long hesitated to do — if someone could show him a definitive standard by which to measure it.

That standard, created by a University of Chicago law professor, is the “efficiency gap.” If gerrymandering is the dark art of wasting the other party’s votes by “packing” them into districts that they win overwhelmingly, or “cracking” them and spreading them widely and uselessly among a number of districts they cannot win, the efficiency gap is designed to measure the number of wasted votes. Under this measure, the professors, as well as other experts at Stanford and elsewhere concluded, the Wisconsin gerrymander was historic and enduring.

Wisconsin is not the only state closely contested state where Republicans have rigged themselves an enduring majority of seats even when they lose the overall vote by where they have placed the district lines.

In Michigan this November, even as Trump became the first Republican to carry the state since 1988, Democratic statehouse candidates earned more votes than Republicans. But for the third consecutive cycle using these post-2010 maps, more votes will not equal a majority of seats. Michigan Republicans maintained their 63-47 hold over the statehouse despite an 18,000-vote edge for Democrats.

This pattern repeats itself throughout the Rust Belt and other battleground states where the presidential election turned — and this is why this decision holds such promise for small D democracy.

In Ohio, the long-time bellwether, Republicans enacted such an effective gerrymander that this year, according to the Columbus Dispatch:

- In nearly a quarter of races for the state legislature, voters didn’t even have a choice. Democrats had no candidate in 20 races, and Republicans left eight uncontested.

- Of the 87 contested legislative races, only five finished Election Day with a margin of victory within 10 percentage points, and none was within 5 points.

- More than half of the contested legislative races (46) were decided by more than 30 points. That includes the 22 percent of races that were decided by more than 40 points.

- None of the 16 congressional races was within 19 points, and 14 were decided by at least 30 points. Incumbents won them all.

- The average margin of victory in the congressional elections was 36 points.

In North Carolina, the GOP retained veto-proof supermajorities in the House and Senate, but with just 53 percent of the vote. That equated to 62 percent of the House seats. And again in Wisconsin, the two parties split the overall vote almost exactly, but Republicans took two-thirds of the assembly seats.

This isn’t about geography. After all, when Democratic legislative candidates managed to win more votes in Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin in 2008, they were able to control the chamber. When they did in 2012, they faced overwhelming GOP majorities. What changed in between? It’s not that all the Democrats in the state moved to the cities. They were simply penned into as few districts as possible for intentional partisan gain.

Indeed, the states where Democrats made their few congressional gains this year were Florida and Virginia — and most of these victories came in new districts that the judges had ordered redrawn because the GOP gerrymander went too far. (This is why GOP veteran John Mica lost in Florida, for example. The New York Times, naturally, keeps referring to him as a victim of Trump.)

Here’s why this matters: As Democrats flagellate themselves for losing Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin on the presidential level for the first time since the 1980s, the party has embarked on a phony debate about how to re-attract the white working class. This is the wrong strategy. Instead Democrats need to pursue democratic reforms that protect the right to vote and the power of that vote. After all, they already have 50 percent or more of the people on their side in these states.

President Barack Obama has already made redistricting reform his top political priority after leaving the White House. His leadership could prove very valuable. Gerrymandering is the topic that puts people to sleep in civics class. Democrats need to make the case that Republicans have drawn lines in a way to rig the system and make policy outcomes that a vast majority of the country support end up being beyond the reach of the ballot box. No one is in a better position to explain this than Obama.

But a political fix would require Democrats to win back enough state legislative chambers by 2020 in order to affect the next national redistricting. They will be outspent by Republicans and need to do something they’ve yet to pull off — win a majority of seats on these brutal maps. That’s an uphill and unlikely fight, even with President Trump.

This decade is likely gone. A judicial remedy — despite the inherent risks of pinning hope on Justice Kennedy —remains the best hope of the Democrats and of us all for elections after the 2020 Census (that will actually be won by the party with the most votes, whichever party that may be).

It may be late in the decade before this case reaches the Supreme Court. The Wisconsin judges did not order new maps right away; instead they called for new arguments on what an effective remedy would be. But they may have found the best remedy in the inspiring tone of their decision. “An intent to entrench a political party in power signals an excessive injection of politics into the redistricting process that impinges on the representational rights of those associated with the party out of power,” wrote Judges Ripple and Crabb.

Our democracy may be on life support, but it’s not too much to suggest that this ruling returns a slow, beating pulse.

Shares