Revolutionary leader Fidel Castro died this week at age 90. The former Cuban president, known to his countrymen as El Comandante, survived 10 U.S. presidential administrations — and also hundreds of assassination attempts by the CIA.

After he helped establish the Republic of Cuba in a 1959 revolution against a U.S.-backed right-wing dictatorship, many players in the U.S. government criticized the socialist leader and his new administration — and so it remained for decades.

Immediately after Castro's death, President-elect Donald Trump took to Twitter to dismiss Castro as a "brutal dictator"— days before he made the draconian proposal that Americans should lose their citizenship for burning the U.S. flag in protest (an activity protected by the Constitution).

In February, when President Barack Obama eased some of the U.S. government's harsh sanctions against Cuba after five decades, he condemned the human rights record of the tiny island nation. "America will always stand for human rights around the world," he insisted.

This is ludicrous to hear from the leader of a country that's now bombing six Muslim-majority countries and helping grind impoverished, hunger-stricken Yemen into dust. Not to mention that Obama leads a superpower that imprisons the most people in the world, forces refugees and migrants into privatized, for-profit, internment camp-like detention centers and deports millions of them. Plus the U.S. props up brutal dictatorships in the Gulf and beyond and unarmed black people are repeatedly killed by police and indigenous "water protectors" are brutalized.

Yet the hypocrisy of the U.S. criticizing Cuba over human rights is even harder to grasp when one considers that the part of Cuba with the worst human rights practices is the area controlled by the U.S.

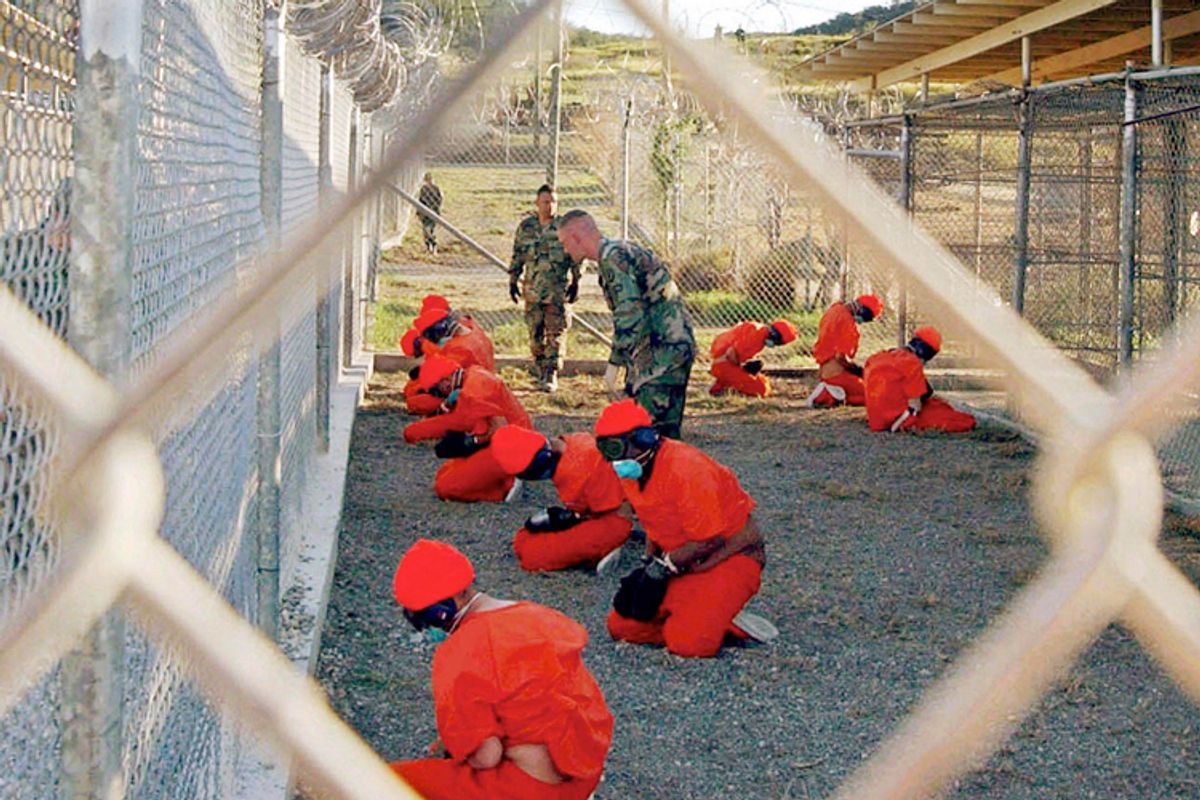

At the Guantánamo Bay naval base, the U.S. has imprisoned hundreds of people without trial; many have been tortured. President Obama has pledged countless times to close it; he campaigned in 2008 on such a promise. Yet it remains open — with many of its former prisoners released, but still open nonetheless.

The Cuban government considers the U.S. military base at Guantánamo Bay to be on illegally occupied turf. The U.S. considers Guantánamo its rightful property; after all, the U.S. seized it when it turned Cuba from a Spanish colony into a de facto U.S. colony in the bloody Spanish-American War of 1898.

Torture is by no means the only human rights abuse committed on this soil, nor are U.S. crimes from the post-9/11 period. In the early 1990s, Guantánamo Bay was used to detain Haitian refugees who had fled a regime initiated by a CIA-backed coup in their impoverished country. The administrations of both George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton used the HIV/AIDS scare to justify forcing tens of thousands of desperate Haitians into what a U.S. federal judge described as a squalid "HIV prison camp."

A legacy of U.S.-backed terrorism

The evident contradiction of American politicians making such moralistic pronouncements is further compounded by the history of U.S.-backed terrorism in Cuba.

As Salon detailed in a previous story, the U.S. has terrorized Cuba for more than 50 years, since Castro led the revolution that freed his country from the yoke of American imperialism. Scholar Noam Chomsky has called U.S. policy in Cuba a “terrorist campaign” and a decades-long “murderous terrorist war.”

In 1978 Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and historian Garry Wills wrote in The New York Times about the U.S. “campaign of terror and sabotage directed against Castro.” Even establishment historian Arthur Schlesinger, who advised president John Kennedy and his brother Robert, spoke of the U.S. attempt to unleash “the terrors of the earth” on postrevolutionary Cuba.

Two years after the Cuban revolution of 1959, the U.S. launched a military invasion of island, attempting to violently overthrow a government that it admitted was very popular and killing and wounding hundreds of Cubans, perhaps thousands according to some estimates.

Former U.S. attorney general Robert Kennedy wrote in notes about a 1961 White House meeting, "My idea is to stir things up on island with espionage, sabotage, gender disorder, run & operated by Cubans themselves." He added that that “no time, money, effort — or manpower — be spared.” People at the White House meeting discussed using chemicals to incapacitate Cuban sugar workers and considered encouraging “gangster elements” on the island.

What has been the U.S. government's goal since then? Since the 1960s, it has strived to, in the words of Lester Mallory, the former deputy assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, "bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow" of Cuba's revolutionary government, to "decrease monetary and real wages" through "disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship."

In order to do so, the U.S. imposed a destructive and crippling unilateral embargo on Cuba for 55 years, an embargo that has taken a huge toll on the country' civilian population and that that has been vigorously opposed by much of the international community.

The U.S. pressure has not just been economic; it has often been violent. From 1959 to 2006, the CIA reportedly pursued at least 638 assassination attempts against Castro, according to Cuban intelligence. The documentary film "638 Ways to Kill Castro," produced by the U.K.'s public media network Channel 4, detailed a vast array of failed murder strategies organized by the United States.

Cuban civilians have also been killed by right-wing terrorists trained by the CIA and harbored by the U.S. government: Luis Posada Carriles, called "the Osama bin Laden of Latin America," previously worked for the CIA — though the FBI later designated him a terrorist. A declassified U.S. government document shows Posada Carriles likely planned the 1976 bombing of Cubana airlines' Flight 455, which killed 73 people. Today, he lives in Miami, according to Diario Las Américas.

Similarly, when asked in "638 Ways to Kill Castro" if he had been behind the civilian airliner bombing, U.S.-backed exiled Cuban terrorist Orlando Bosch replied, "I'm supposed to say no," before going on to insist that anything is justified in war against Castro. Bosch infamously declared, “All of Castro’s planes are warplanes,” including civilian Cuban aircraft. Even Dick Thornburgh, U.S. attorney general under presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush senior, called Bosch “an unrepentant terrorist.” (Bosch died of old age in Miami in 2011.)

U.S. plots to destabilize and overthrow Cuba's government have continued through the Obama administration, through the terms of all presidents, regardless of party. In 2014, two more schemes were exposed — one relying on a fake Twitter-like website created by the U.S. Agency for International Development to spread anti-government misinformation and another involving infiltration of Cuba's hip-hop scene in an effort to stir up dissent.

In other words, after 57 years and countless foiled plots, the most powerful country in the world failed to crush a country that waged a revolution against it, and a tiny island nation that withstood its constant wrath.

Despite the incredible hardship and the concerted effort to destroy it, Cuba has endured. It still managed to create some of the best health care and education systems in the world. The revolution transformed a former U.S. colony plagued by health problems, illiteracy and extremely uneven development into a country with the best education system in Latin America and one with a lower infant mortality rate than that of the U.S.

Yes, Cuba does not have the standards of living of industrialized Western countries. But these countries developed their economies through centuries of colonialism, imperialism, enslavement of human beings and brutal exploitation of foreign lands. Comparisons to Cuba are almost always out of context; it is not contrasted with neighboring countries like, say, Haiti (where the U.S. has backed two coups since 1991 and worked with multinational corporations to block a minimum wage increase to a paltry $0.62 an hour).

There would be much to gain from a nuanced discussion of Castro's legacy — preferably one conducted by the Cuban people itself. There should be a hard look both at the enormous benefits and gains of but also at the real failures and problems with the Cuban government. Yet the U.S. is in no position to make such judgments; it has tried ceaselessly for more than five decades to crush that government.

Shares