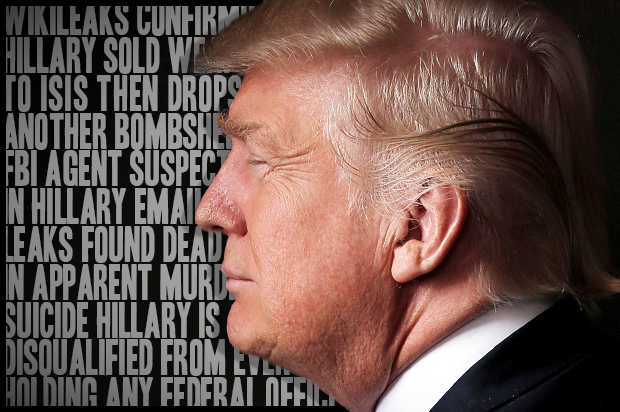

How much of the “news” is fake? How much of reality is “real”? After an election cycle driven by lies, delusions and propaganda — including lies about lies, multiple layers of fake news and meta-fake news — we are about to install a fake president, elected by way of the machineries of fake democracy.

The country that elected him is fake too, at least in the sense that the voters who supported Donald Trump largely inhabit an imaginary America, or at least want to. They think it’s an America that used to exist, one they heard about from their fathers and grandfathers and have always longed to go back to. It’s not.

Their America is an illusion that has been constructed and fed to them through the plastic umbilicus of Fox News and right-wing social media to explain the anger and disenfranchisement and economic dislocation and loss of relative privilege they feel. All of which are real, if not necessarily honorable; it represents the height of liberal uselessness to keep on quarreling about whether Trump’s fabled “white working class” suffers real economic pain or is just a cesspool of racism.

That argument is really about other things, to be sure: It’s about whether the Democratic Party — whose long-promised era of permanent demographic hegemony and middle-class multiculturalism keeps being delayed into the indefinite future, defeat after defeat after defeat — requires a major reconstruction or just a little cosmetic surgery. Meanwhile, out in the pseudo-reality of Trumpian America, racial resentment and economic suffering are so profoundly intertwined that there’s no way to disentangle them.

Arguments that the so-called left should pretty much ignore the deplorables who keep on voting against their own interests, or should abandon “identity politics” in quest of some middle-road economic populism that blends Bill Clinton and FDR, are both missing the point. In a nation where a candidate who won the popular vote by roughly 2.5 million did not win the election, we are no longer dealing with reality, at least as it used to exist.

Hillary Clinton was the ultimate Establishment candidate facing the ultimate outsider, and also a quintessential old-media personality facing a veritable Voldemort of social media. Given that, she came pretty damn close to pulling it off. But Clinton was also a candidate from reality facing a shimmering celebrity avatar, a clownish prankster who took physical form in our universe but who could say anything and do anything because he was self-evidently not real. That disadvantage proved impossible to overcome.

Furthermore, Trump’s supporters may be delusional and misguided, but they aren’t half as dumb as they often look to “coastal elites.” Many of them understood, consciously or otherwise, that his incoherent promises could not be taken literally and that his outrageous personality did not reflect the realm of reality. They were sick of reality, and you can’t entirely blame them. For lots of people in “middle America” (the term is patronizing, but let’s move on) reality has been so debased, or so much replaced, as to seem valueless.

If reality means lives of pointless service-sector drudgery, downward mobility or stagnation, fast-food dinners, opioid addiction and traffic jams, then escape into fantasy seems forgivable. Donald Trump is a creature of the nurturing electronic cocoon that disrupts or replaces reality, an overlord of consumerism. (He is not in any meaningful sense a “capitalist.” Capitalists produce things, in the real world.) To paraphrase Michael Moore, Trump represented a historic opportunity to extend a giant middle finger to reality itself, and to the forces that have rendered it so dismal.

When I suggested a few weeks ago that Trump’s worldview resembled the narcissistic simulated universe of “The Matrix,” I had no idea how far the analogy would go. His election represents the moment when roughly half our voting population — slightly less than that, to be fair — spoke out clearly: Give us the blue pill! That’s the one where you wake up in your beds and believe whatever you want to believe, leaving reality behind. If onetime movie star Ronald Reagan was the first postmodern president (the word still meant something back then), Trump will be the first post-reality president.

That more or less explains my problem with the Jill Stein recounts and the faithless-elector dreamers and the people who write to me saying that Salon should not use the term “president-elect” to describe Trump because it isn’t accurate until the Electoral College convenes on Dec. 19 and for the love of God, he can still be stopped. Such people are clinging to the norms and standards of an outdated reality; they are almost as deluded as the Trump voters, and more overtly pathetic.

Somehow the light of reason and the Enlightenment wisdom of the Founding Fathers can remedy this situation, they tell us. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson didn’t agree on much, but they wouldn’t have wanted an ignorant buffoon and obvious demagogue elected over a competent states(wo)man who got more votes, thanks entirely to the flukes of national geography and demographic division. The authors of the Constitution gave the Electoral College full autonomy to override such an outcome.

I’ve already bored myself half to death trying to convey that stupid argument fairly: The problem isn’t that it’s untrue but that it is hilariously irrelevant. All the greatest constitutional minds at Harvard Law can’t argue America out of the Matrix. Furthermore, try to imagine what would happen if they could. If recounts in all three of those Rust Belt states somehow reversed the results, or if 270 electors contrived to vote for Clinton or Mitt Romney or, I don’t know, some David Brooks-approved “centrist” from Central Casting, what would the aftermath of that event look like among a population whose storm windows are already rattling dangerously in the wind? Do you even want to live through that? An America where such a constitutional antidote might restore our collective sanity is even more imaginary than the one Trump force-fed his supporters.

On the unhinged outer fringes of “this can’t have happened” liberal denialism, we find the thesis that the Russians are to blame for Trump, which feels like a grotesque parody of right-wing paranoia about Communism, circa 1959. There are certainly websites that circulate pro-Russian propaganda, just as there are sites that spread every other possible variety. But the idea that a sinister campaign of “fake news” and calculated leaks sponsored by Vladimir Putin sank Clinton and got Trump elected rests atop a pyramid of logical fallacies and unproven assertions, most prominently the premise that anyone who criticized Clinton’s hawkish foreign-policy agenda or her ties to Wall Street — indeed, anyone who criticized mainstream political orthodoxy in any way — could only be a Putinite tool or a “useful idiot.” (Given that, I was slightly disappointed that Salon did not end up on the red-scare list of supposed Russian propaganda sites compiled by anonymous internet loons, alongside CounterPunch, Truthdig, the Drudge Report and dozens of others. What did we do wrong?)

Last week in this space, I suggested that the path of political responsibility, in this time of permanent national emergency, is to take the parallels with Germany in the early 1930s seriously. There are obvious differences. Trump is nowhere near being Hitler and the mass of people behind him have nowhere near the organization or discipline to be the Nazi Party. Some of them halfway wish they did, perhaps, but they all want other people to do the hard work of concentration camps and genocide and marching around with torches. They stand ready to live-tweet that stuff as it happens.

In pragmatic terms, I believe we must behave as if democracy were in dire and perhaps terminal peril, and as if this might be the moment when our two-century-plus experiment in republican self-government tips over into squishy, soft-focus and nearly content-free fascism. But even that analysis, on reflection, feels too limited. It’s too closely tied to the vanquished world of reality, the world where history mattered and where actions were understood to have consequences. The world of context.

Because we seem to have arrived now at the moment imagined by cultural critic George W. S. Trow in a memorable essay called “Within the Context of No-Context,” which was published 36 years ago in the New Yorker and became the basis for a book of the same title. Coincidentally or otherwise, Trow’s original article appeared in the same month Ronald Reagan was elected president.

Trow described a process of cultural devolution in which history, previously “the record of growth, conflict, and destruction,” had become a chronicle of quantifiable marketing, “the record of the expression of demographically significant preferences.” In this new era of no-history, “nothing was judged — only counted,” and old-fashioned qualities like the “power of judging” and the “refining of preferences” were deemed unnecessary. “The preferences of a child,” he wrote, “carried as much weight as the preferences of an adult. . . . The most powerful men were those who most effectively used the power of adult competence to enforce childish agreements.” He did not know we would one day elect a president with the vocabulary of a middle-school child. (Some say fourth-grade, others say fifth.)

Trow’s entire essay reads as eerily prefigurative from this distance. I had been meaning to give it a read ever since election night, and now I know why I felt reluctant. If his dark utterances about the meaninglessness of politics felt a bit too apocalyptic for 1980, they don’t feel that way now. If his jeremiad against television — as “the force of no-history,” a medium with a uniform and unvarying scale where “the trivial is raised up to power” and “the powerful is lowered toward the trivial” — seemed overly sweeping at the time, it describes the political effect of Internet discourse and social media with precision.

Here is Trow’s opening paragraph. Reading it again sent chills down my spine:

Wonder was the grace of the country. Any action could be justified by that: the wonder it was rooted in. Period followed period, and finally the wonder was that things could be built so big. Bridges, skyscrapers, fortunes, all having a life first in the marketplace, still drew on the force of wonder. But then a moment’s quiet. What was it now that was built so big? Only the marketplace itself. Could there be wonder in that? The size of the con?

Undoing the Trumpian moment and combating Trumpism is not a matter of enforcing the Constitution or reforming the Electoral College or even about fighting against policies redolent of fascism, although those things won’t hurt. It’s about escaping the Matrix. It’s about undoing the wonder of the con. It’s about asserting that there is a reality to return to and to wonder at, a place of earth and sky and human life. We have to convince ourselves that is true before we can convince others.