When it comes to the movies, Donald Trump’s tastes are far from surprising. He’s a big fan of widely-heralded hits like "Citizen Kane," "The Godfather" and "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" and has at times expressed admiration for gaudy action flicks like "Bloodsport" and "Goldfinger." Based on his history of pontificating, bullying and self-promotion, the idolization of mythic cowboys, violent gangsters and James Bond-types is to be expected. Plus, everyone picks "The Godfather."

Yet, according to a list he gave Movieline a few years back, the president-elect also put 1939’s "Gone With the Wind" in his top five. Which might seem like another obvious choice for the man — a showy classic, the most expensive film ever made in its day — but it’s actually a bit more revealing. Not only because the Civil War drama expresses a more openly white supremacist view of history than his other picks, glamorizing “the Old South” in a way that mirrors his revisionist campaign slogans (Variety’s 1939 review mentions the film’s “memorable views of plantation life”). But it’s especially notable because "Gone With the Wind" is a love story, a romantic film.

Earlier this year the BBC described Trump as “a bit of a romantic” for this choice, a sentiment shared by Movieline in 2012. Which, to put it mildly, is not how many today would describe a man who once said “a person who is flat-chested is very hard to be a 10.” Then again, considering how many Americans seem to have overlooked the sexual assault allegations against this same man who can be heard on tape bragging about groping women, perhaps there’s something more to that characterization. After all, how does an ideal man treat women anyway? What does a “romantic” really look like?

The American Film Institute lists "Gone With the Wind" as the second greatest romantic film ever, and in one 2009 poll, readers ranked Wind’s Rhett Butler as the fifth most romantic character in all of literature. Clark Gable’s interpretation of Rhett — with all his “frankly dear, I don’t give a damn” attitude — left an indelible impact on Hollywood’s depictions of American men in love for decades.

At the same time, the film has been criticized for glamorizing marital rape, through the scene where, after a night of heavy drinking, Rhett picks up Scarlett O’Hara and forces her to bed. Not to mention the general disregard he has for Scarlett’s autonomy throughout the story. (She also happens to be 15 years younger than him.)

How much really separates Rhett from the men in other widely-celebrated films, characters like Charles Foster Kane or the Corleones? Alison Willmore writes that our next president may identify with the former specifically because he is a hero “undone by the inadequacy of his women, their failure to be compliant, appreciative companions.” And in a 1973 essay, The Atlantic’s Stanley Kauffmann wrote of "The Godfather" and "Gone With the Wind" that “both are about predators … both live within codes of honor, and both codes are romances.”

These films have their complexities, and Mr. Trump is far from the only one who admires them, but perhaps his frightening political ascent might shake us into paying greater attention to the overall messages about love and masculinity that Hollywood continues to sell. Because maybe part of the reason so many have fallen for Trump is that our grandest form of entertainment has long been training the world to see something admirable in those straight white men who dominate others. Those who just don’t give a damn.

We may actually find them a bit romantic.

***

In 1959’s "Pillow Talk," released three years before the first Bond film, Rock Hudson defined a certain version of the “ladies man” in romantic cinema. His character, Brad Allen, is a well-off single songwriter who actually has a switch next to his couch which turns it into a bed, puts on a record and dims the lights in one fell swoop. But when he catches a glimpse of his attractive neighbor Jan Marrow, played by Doris Day, he poses as a southern "gentleman” in hopes of seducing her (she’s a “career woman” with a preexisting dislike of him). Dr. Kathrina Glitre describes this genre of film, in her book "Hollywood Romantic Comedy: States of the Union, 1934–1965," as such:

She wants love (and marriage), he wants sex (without commitment). Courtship patterns are confused: in most cases, the woman thinks she is taking the lead, but only because the playboy has resorted to devious methods of seduction.

In the end the man “settles down” and decides he really does want love, while the woman often has a kind of awakening, realizing she maybe doesn’t want a gentleman after all. There are variations on this plot, of course — in modern films like "How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days" or "Down With Love," for instance, both the man and woman play tricks on each other — but the resolution remains familiar, and the dominant role of men is rarely challenged.

One tragedy of the heteronormative center of "Pillow Talk" is that Hudson himself was gay, forced to keep his identity hidden. But almost 60 years later Hollywood continues to portray love as a mostly straight experience — and one primarily for attractive, thin, able-bodied white people. In particular, one of the functions of romantic plots in popular film, it seems, is to vindicate the otherwise terrible ways in which straight men treat women. Or as Patricia Garcia at Vogue observes about "Jerry Maguire," “sometimes all a man has to do in order for you to forgive him is to show up.”

This coddling of men on screen isn’t only a result of cultural gender norms, but how the film business itself reaffirms those limiting ideas. The movies we call “romantic” — whether they are comedies, dramas, or musicals — haven’t just been marketed to women for decades, but have often been explicitly characterized as not for men. There’s maybe no better example of this in recent times than the ironic Valentine’s Day campaign created for Ryan Reynolds’ "Deadpool" presenting the gory, profane superhero film as a romantic comedy — inspiring men online to re-cut the trailer in an effort to “trick” their girlfriends into accompanying them to see it.

What we tend to avoid admitting is that many men do watch so-called “chick flicks,” and that they have almost always made them as well. In fact, the vision of romance Hollywood has constructed over the past 100 years has mostly been the vision of straight white men. Like most Hollywood films, all but one of the top 25 romantic dramas of all-time, based on box office receipts, were directed by men. Of the top 100 romantic comedies of all-time, only 13 were directed by women. And nearly every single one is about white people. It’s not surprising then that even though these films are more likely to star women — and be associated with femininity — they still tend to reinforce dominant ideals of masculinity.

One of the key messages films like “Pillow Talk” send — just like a Bond movie — is that the kind of reckless path that Brad Allen takes is actually the ideal one. Sure, the man manipulates many beautiful women into his bed, but he's ultimately unfulfilled by it (though much of the film shows him enjoying it quite a bit) and he’s actually a great guy underneath it all. Or in the words of Deadpool, “The right girl will bring out the hero in you.”

Yet, significantly, Brad Allen’s journey also involves treating women like disposable objects and ignoring their consent. That switch next to his couch? Beyond aggressively setting the mood, it also locks the door.

Thus the ghost of the “ladies' man” haunts us still, and certainly showed up frequently this year. Our next president has reportedly said, “Women find his power almost as much of a turn-on as his money” — in reference to himself. But Trump’s adherence to this mode of manhood was made most apparent on that now infamous tape, on that bus, in the words we can hear him saying to another white man, bragging about kissing and grabbing women whenever he pleased. Perhaps Donald Trump believed it was what those women wanted, what he deserved from them and what would gain him respect from other men. Or at the very least, that he could be forgiven for anything — as long as he showed up as a powerful, wealthy, straight white man.

***

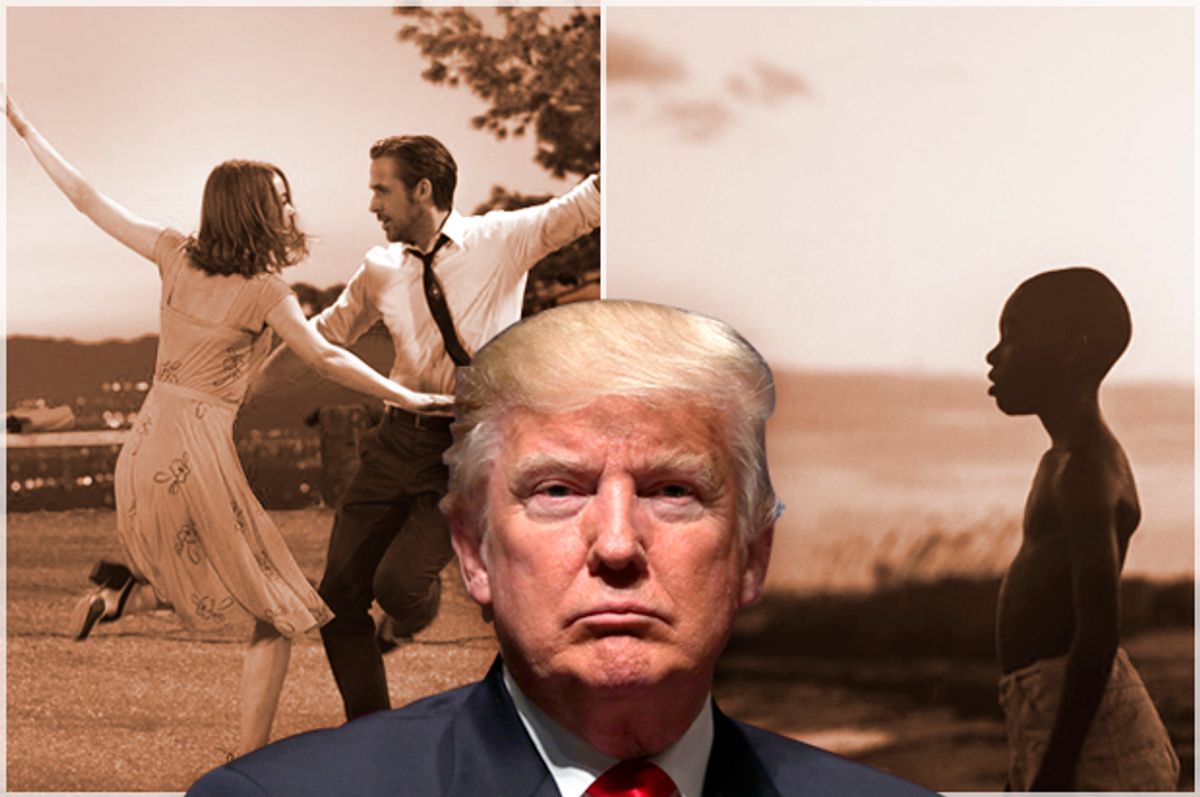

In the wake of Trump’s election arrives Damien Chazelle’s "La La Land," a romantic musical starring Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone as star-crossed lovers Sebastian and Mia. For some, the film feels like the perfect antidote to the dark cultural moment and an Oscar race that has itself been plagued by multiple allegations of sexual harassment and assault.

Though in many ways the mere fact of Gosling dancing and singing across the screen challenges stereotypical notions of masculinity, in other ways his character reaffirms the most familiar ideals. Sebastian expresses himself beautifully through music, but he’s also a jazz purist to an extreme degree, much like the male protagonist of Chazelle’s last film, "Whiplash." And that means he pines for a time that has passed, both musically and culturally — a time when he might have more easily swept Mia off her feet.

Romance in the movies is often tied to this kind of nostalgia, but relying on Hollywood’s historic definition risks more than the continued exclusion of certain groups. For instance, "Gone With the Wind"’s stubbornly popular kind of romantic love not only glorifies Rhett Butler’s paternalism, but keeps a specific idea of the rebellious “gentleman” central in our cultural imagination: the kind-hearted and dashing rogue, who knows better than women, and is determined to protect his culture at all costs. Which is, of course, often a culture of whiteness.

"La La Land" does not traffic in the blatant racism that imbues "Gone With the Wind " — or Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” campaign — and it makes sure to pepper in people of color throughout the film, from background parts to the film’s sort-of antagonist, Keith, played by John Legend. And there is no denying the contrast made between the diverse backdrop of people at the parties Mia attends and the all-white murals she walks past, depicting the Hollywood stars of yesteryear.

And yet, though Chazelle is clearly aware of the facade of the Hollywood dream, he lingers within it. There is indeed a melancholic element to Mia’s story arc, and neither she nor Sebastian gets all of what they want, but they do achieve success in L.A. And though the director seems to suggest that an old-fashioned seriousness about art and Hollywood’s commercialized future are incompatible, he charts a generally optimistic path through the center for his stars. One which ultimately leaves us with a white man back in the spotlight on stage, black men off to the sides, and the director himself with a likely Oscar nomination.

So perhaps, as Nick Pinterton writes, "La La Land" “doesn’t want to bridge the last sixty-odd years so much as pretend they never happened.” In that sense, the film’s most stirring moment may be its very first one: In a musical filled with cinematic flourishes — dances in the clouds, dizzying long takes, and beautifully colored sunsets — there is nothing quite as surprising as that initial swooping dive into a sea of traffic to find the face of a woman of color sitting alone in her car, dreaming about seeing herself on screen.

Played by Reshma Gajjar, and listed simply as “Traffic Dancer — Girl #1” in the credits, the character’s appearance at the outset stands out, but is actually only the first of many faces of color in that musical sequence. As people emerge from their cars to sing and dance in unison — while stuck in that never-ending LA slog — it becomes a kind of magically inclusive ode to the resiliency of hope.

Yet, by the end of the film — actually, soon after that opening number — we realize that the dream is still not for everyone. Or rather, that we’re not all dreaming of the same thing. In Chazelle’s still heteronormative world, straight men can indeed dance, but the gender and racial politics haven’t changed all that much from the time of "Pillow Talk." Certain people are still destined to remain “Traffic Dancer — Girl #1,” while others get their moment in the sun, singing about the way things used to be.

The more encouraging romance this Oscar season then is Barry Jenkins’ "Moonlight," which provides an example of what’s possible when the spotlight shifts more significantly. The film, based on a semi-autobiographical play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, tells the coming-of-age story of a Black boy named Chiron, and features more than one man who communicates with warmth — despite being a film largely about the ways in which men are taught to keep themselves sewn up.

There is no shortage of cinematic nostalgia in Jenkins’ direction either, but most of its looking backward is in service of pushing things forward. There is this particular moment at the very end of the movie, when Chiron (played as an adult by Trevante Rhodes) admits to another Black man that he hasn’t been touched in years, where through his sensitive gaze, his body language, his painful confession, the screen is enveloped by longing — a divulgence of need for emotional and physical intimacy.

As the film glides to an end, and these two people embrace at the edge of a bed, it’s this lingering feeling of warmth which most powerfully threatens the persistent lie of patriarchy: that nonviolent, “feminine” caring is beyond the reach of men. In the time of Trump, as the new administration seeks to celebrate a model of white manhood rooted in dominance and aggression, Jenkins’ work lights a necessary path of resistance for cinema. One where we recall the healing power of love, and of actually giving a damn about others.

Shares