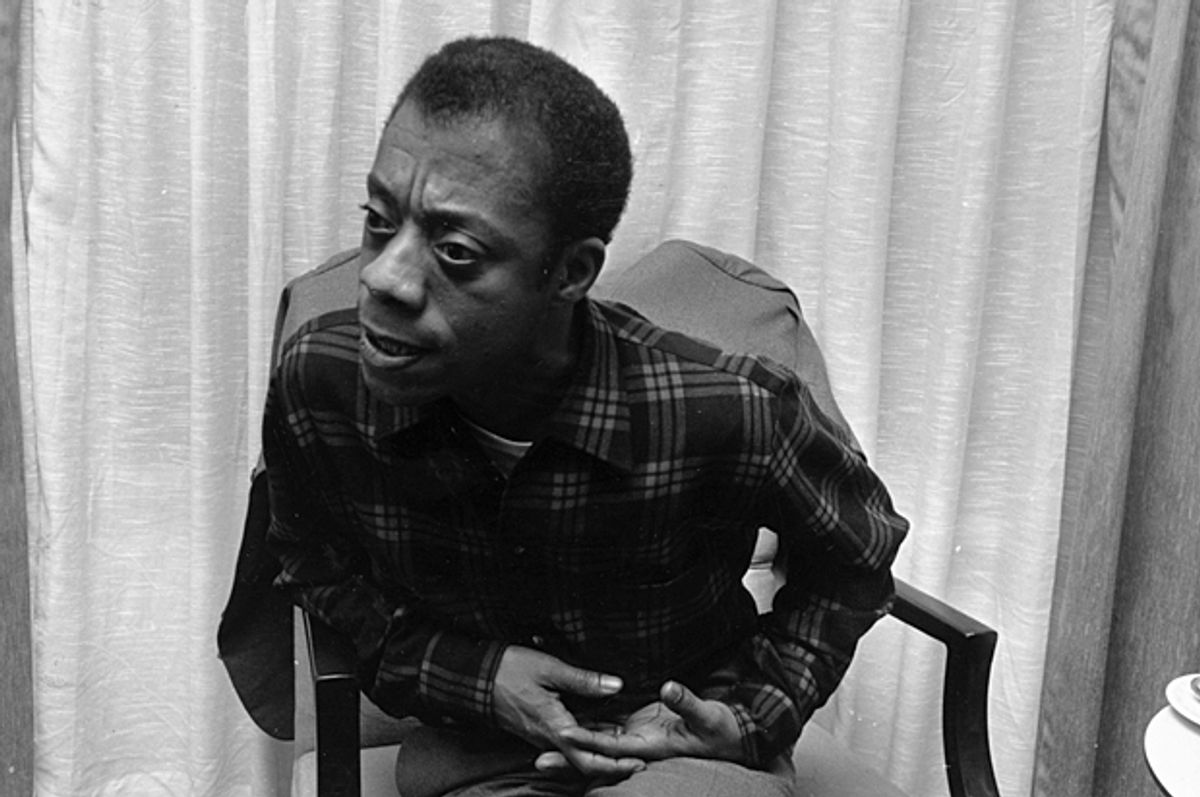

Beacon Press published James Baldwin’s classic essay "A Stranger in the Village" in 1955, but it’s as relevant today as it was then — maybe even more so because of what happened in this past troubling year. In his essay, Baldwin described how he moved to a remote Swiss village where no one had ever seen a black person. Children joyfully shouted, “Neger! Neger!” as he walked on snowy streets. Older villagers treated him well but with a detached curiosity. “There was no suggestion that I was human: I was simply a living wonder.”

Baldwin then used his experience as a metaphor to describe the larger disconnect between white and black America. Black Americans, he said, carry with them a mixture of rage and hope — rage from the yoke of history, rage from being treated as strangers decade after decade, and hope that says “when life has done its worst they will be enabled to rise above themselves and to triumph over life.”

Meantime, white Americans filter racial reality through the combined prisms of naivete and revisionism. Like the Swiss villagers, a white American prefers to keep black people, Baldwin wrote, “at a certain human remove because it is easier for him thus to preserve his simplicity and avoid being called to account for crimes committed by his forefathers, or his neighbors.”

This gap will be felt for generations, Baldwin predicted several generations ago. The root of the problem is “the necessity of the American white man to find a way of living with the Negro in order to be able to live with himself.” Ultimately, black or white, “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

I read Baldwin’s essay after two seismic events, one national — the long and bitter election of a man who yoked his campaign to revisionism — and for me, one local: the murder trial in Charleston, South Carolina, of Dylann Roof.

Roof was the punk who fed his distorted imagination with internet-fueled nonsense and gunned down nine black churchgoers during an evening Bible study. The trial, in the second day of the sentencing hearing, exposed Roof’s twisted views of race and motivations to kill.

“Somebody had to do it,” he told police in a videoed confession. “Black people are killing white people every day. . . . What I did is so minuscule compared to what they do to white people every day.”

Sick as Roof is, his views reflect something deeper, and Baldwin nailed it 60 years ago in “A Stranger in the Village.”

“The idea of white supremacy rests simply on the fact that white men are the creators of civilization . . . and are therefore civilization’s guardians and defenders. Thus it was impossible for Americans to accept the black man as one of themselves, for to do so was to jeopardize their status as white men.”

Baldwin’s discussion about identity also sheds light on why black Americans can simultaneously hold feelings of rage and hope. It’s a lesson we saw during Roof’s bond hearing when the victims’ family members talked about anger and forgiveness in the same breath. In doing so, they lead the city, white and black, away from a riotous path.

Yet, Baldwin leaves little room for optimism. Black people aren’t visitors, Baldwin says. Slavery and its legacy forged “a new black man” and “a new white man, too.” But “American white men still nourish the illusion that there is some means of recovering the European innocence, of returning to a state in which black men do not exist,” he wrote. “This is one of the greatest errors Americans can make.”

And 60 years later, a good many Americans are still making these errors. Too many white Americans treat nonwhites as if they don't belong in the country. ("Build that wall! Build that wall!") The Black Lives Matter movement is rooted in resistance to this notion. White Americans who yell back, "All Lives Matter" share the naïveté that Baldwin spoke of in 1955, as they are confident in their birthrights to a village that exists more in their mind than reality.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Baldwin’s heir, wrote an equally brilliant essay in this month’s The Atlantic.

In "My President Was Black," Coates wrote about Obama’s unusual optimism, a hopeful perspective rooted in Obama’s unique biography: a man born to a white mother and a black African father, who grew up among a loving white family and then chose to fully explore his black identity. The country’s first black president wasn't a stranger in any village.

And yet some Americans still treat Obama like a visitor. They take his biography and bend it in violent shapes: Obama the Muslim, Obama the Kenyan.

And now with Donald Trump’s election, a large number of white Americans can tell themselves, “Yeah, he was only passing through.”

Increasingly, we’re all strangers now.

But it’s a fool’s errand to turn back time. No road “will lead Americans back to the simplicity of this European village where white men still have the luxury of looking on me as a stranger,” Baldwin wrote. “This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again.”

Shares