Fine art is at a crossroads. For the past 10 years, museum attendance around the world has continued a steady decline. Indeed, the stuffy world of maze-like museums seems at odds with our digitized, 21st-century culture. The musty paintings of old masters feel entirely out of touch to a youth eager for sexuality, irony and diversity. What could “The Starry Night” possibly contribute to the the life of a 21-year-old woman of color who is working as a hostess while finishing a computer science degree? It would look nice framed above her Ikea couch, but what else?

The art in question hasn’t changed, and it’s not going to. The Mona Lisa still smiles the same way she did for da Vinci himself. The issue lies with the fact that the way the world sees art has failed to adapt. Fine art, portrayed as cold and unfeeling, is at odds with our emotional reality. Yet the key to reanimating these artifacts can be found in the most unlikely, if not most relevant source: memes.

***

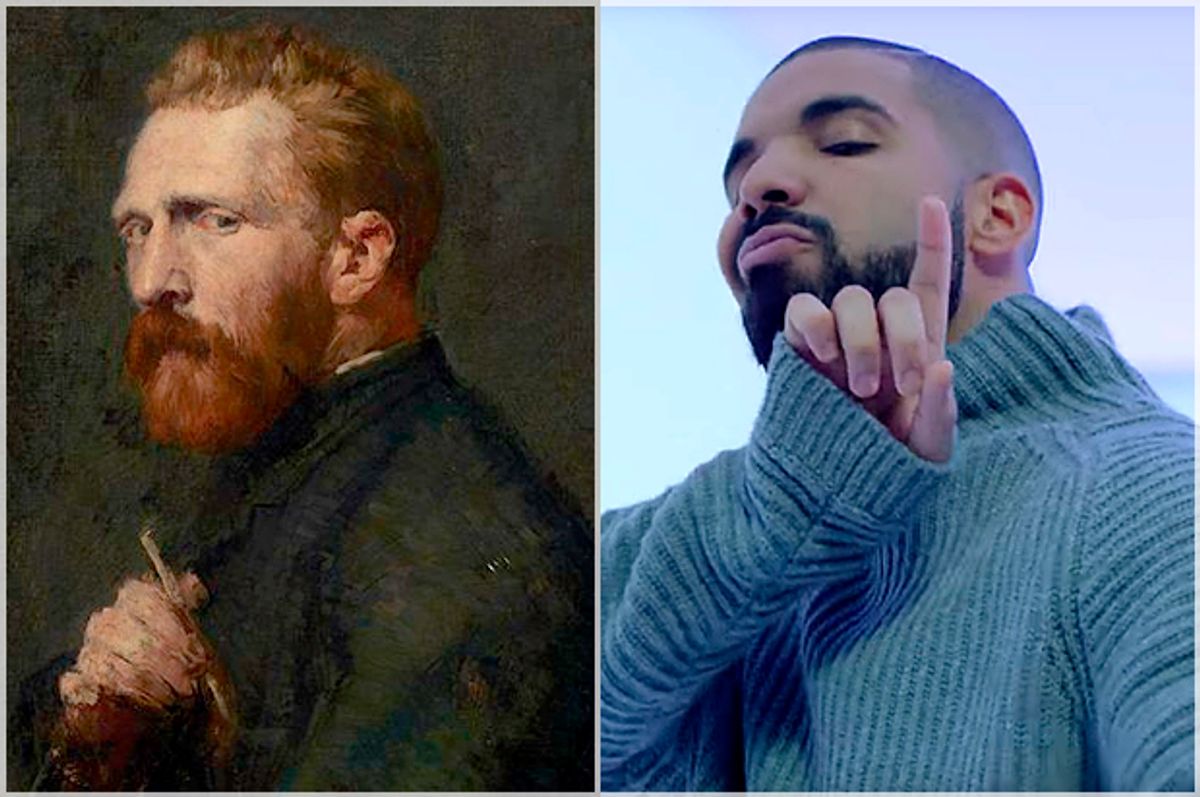

Picture two images: One, a still of Drake from his 2016 “Hotline Bling” music video: cashmere Acne turtleneck, soft cotton-candy lighting. The other, John Peter Russell’s 1886 portrait of Vincent van Gogh: a tired face emerging out of a black cloud. Examined separately, the images show no sign of intrinsic connection: their mediums, their color schemes, their contexts all foreign to each other. Yet, when left in a room together — these images speak. Placed side by side, there is a jolt of recognition: their poses are nearly identical. Their bodies turned away from the viewer, left shoulders jutting out in both contempt and heartbreak, expressions solemn and knowing, right hands raised in creative anticipation.

The desired effect is decidedly less poetic. The side-by-side comparison of these images is a viral hit on sites like 9Gag, Twitter and Tumblr. True, there is a level of humor here: a meeting of the supposed high- and lowbrow that’s too silly to ignore: an image we, as a culture, have reflected upon and glorified for more than a hundred years, paired with a fleeting video still from a short-lived, viral moment in modern music. Yet there is a thread, running deep in the subtext of these images, that connects our innate attraction to them.

Take the subjects depicted: both are male artists in their late 20s, known for creating works that rely heavily on self-reflection, prolificity, and hopeless romanticism. Drake's ceaseless passions may not have inspired him to hack off his earlobe (yet), but for both of these men, portraying a bleeding-heart seems not an overly performative act, but a genuine and necessary expression of emotions in an overly-macho culture. In pairing these images, each artist is illuminated in a new light: Drake, in the underlying anger and mess that modern pop culture so easily hides, and van Gogh in the glow of softness, sobriety and style that often comes last (if at all) in discussions of his work.

***

This convergence of viral culture and fine art is not a short-lived meme, or even new. It's a popular — if niche — form that satisfies the palates of those who worship at the altars of both Michelangelo and the Real Housewives. The Internet has reconciled a schism that artistic scholarship has failed to unify.

One needs to look no further than Fly Art Productions, a core perpetuator of this meme form whose daily Tumblr posts regularly garner upwards of 10,000 reblogs. The mission of Fly Art Productions is simple: take a classic painting and superimpose it with rap lyrics (i.e. "I woke up like this" from Beyoncé's "***Flawless" plastered on Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus"). Some of Fly Art Production’s creations are more successful than others — understandably, not every Tupac quotation is a proper companion to a Waterhouse portrait. And yet, a selection of these images are rife with just as much revelatory depth as the Drake/van Gogh comparison.

Take one of the most recognizable and reused images of all time: Caspar David Friedrich's “Wanderer above the sea of fog” (1818). Fly Art Productions covered the image with the phrase "Lost in the world," the refrain of Kanye West’s song of the same name from his 2010 album “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.” Yes, those particular lyrics reflect the at-a-glance meaning of the painting: a sole figure confronted with nature. And yet putting the 19th-century Romanticism movement in conversation with “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” delineates both pieces of the equation. The painting is accompanied by the roar of drums, the haunting twinkle of a single piano key — the rush of lyrics that are both powerful and lonely, larger than life, yet so easily overwhelmed. Songs like “Runaway” and “All of the Lights” wrestle with intimate themes of love, family and maintaining individual identity in the public eye.

The presentation of these themes in a decidedly un-intimate, brash manner creates a contradiction that makes West a compelling artist. Similarly, Friedrich’s painting is a contradiction between self-reflection in the wake of realizing one’s own insignificance; a visual iteration of the Kantian philosophy that one’s experiences are merely a product of the mind. In return, this philosophy parallels West’s consummate creation of his own artistic universe. Viewers of Friedrich’s painting and listeners of West’s music are intended to be left asking themselves what it means to exist, what can one individual be in the wake of something as grand as the world itself? Thus, both pieces of art become a means to the same end. Looking at Friedrich’s painting and hearing the brashness of West’s lyrics create an entirely new, unique experience in which both elements are brought to new heights.

Another variation on the digital mashup of fine art and pop culture places a modern image alongside a painting, and captions them as though they were both on the walls of the Met. Instagram page We Are All Memes, with approximately 14,000 followers, frequently curates this form. A recent post places the William Henry Margetson painting "A water sprite or siren" (~1896) next to a still of "Kim Kardashian Loses Her Diamond Earrings in Bora Bora" (2011), an oft-lampooned scene from “Keeping up with the Kardashians.” Though this particular example does little to heighten the experience of viewing either image in question, like Friedrich/West and others, this form of comparison breaks down an entirely different wall: our deification of old art, no matter how mediocre.

Before anyone sets the world aflame with the completely original thought that Kim Kardashian is of no artistic or cultural value, consider the fact that Margetson's entire body of work focused solely on depicting women who were beautiful by the aesthetic standards of the time, with little or no concern for substance. On every possible plane, this painting is meaningless, even if there’s a nice brushstroke here and there. Very much like the realm of Kardashian and her show, the intent is not to make us ask difficult questions about the world, but to allow us to dip our toes into a burst of pleasure and beauty, perhaps the very same intent Margetson had when he took up his brush. Both the art and Kardashian’s mirror are expressions of frivolity at its peak. As individuals, it’s unlikely that fans of the mogul and the painting are anything alike. And yet, on this level, they are one and the same.

***

It is worth noting that many of these conversations place contemporary artists (musicians and otherwise) of color opposite white, European painters and white, European subjects. The principal reason that these memes go viral is because of the evident humor in placing the "lesser" arts of hip-hop music and popular culture in conjunction with the high art one sees in textbooks. It's not exactly original to share rap lyrics superimposed on a gritty, graffiti-filled wall, just the same as a Shakespeare quote accompanying Monet isn't likely to incite poetic revolution. Our artistic conditioning predisposes us to believe that these racialized elements should not mix. While there may be a twinge of humor present in Nicki Minaj’s occasional resemblance to Caravaggio's “Medusa,” there is a wealth of new information and perspective to be gleaned about the way we value and interpret different types of art. We place an undue burden on, glorify, even, works that appear in museums or the glossy pages of a textbook; when Internet art and hip-hop are brought into the mix why is our only supposed reaction laughter?

While the everyman’s understanding of art history rarely includes the humor, violence, or frivolity of real life, one is compelled to return to these images again and again. Art provokes a desire to feel, to “get it,” and yet many of us, when confronted with a Monet are left incapable of defining what that framed piece of canvas does to our souls, if not for lack of understanding, then for a lack of vocabulary. Contrarily, despite being one of the most fleeting forms of communication, a meme has a great capacity for both emotional impact and accessibility. By pairing fine art images with other viral forms of communication, whether it be visual or textual memes, we are given the freedom to better understand these artworks in a context that is situated in our modern emotional landscape. It is but another level of freeing ourselves from the conception that elitism is inherent in art.

In “Ways of Seeing,” the late and legendary John Berger wrote, “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sun set. . . . Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight." By utilizing the form of the viral image or music lyric to reflect on classic works of art, we are not weakening our understanding, but deepening it. We are giving a new form of explanation, one with which we are infinitely more well-versed, to the sights that we have so longed to be more familiar with.

Shares