One particularly unsettling portent from the presidential election may have been the role that artists didn’t play. Though political caricaturists and satirists had a field day, no Shepard Fairey stepped forward from the art world to crystalize the ideals and aspirations of a candidate, or to electrify and inspire voters in the way that the Los Angeles street artist’s iconic “Hope” portrait did for Barack Obama in 2008.

Then again, what space was left for art when its traditional license of intellect, invention and poetic imagination was so effectively seized by Donald Trump’s own brand of performance art?

As president, Trump has wasted little time in formalizing his stranglehold on artistic, journalistic and intellectual expression that doesn’t bend to a reality constructed of “alternative facts” and Orwellian doublespeak.

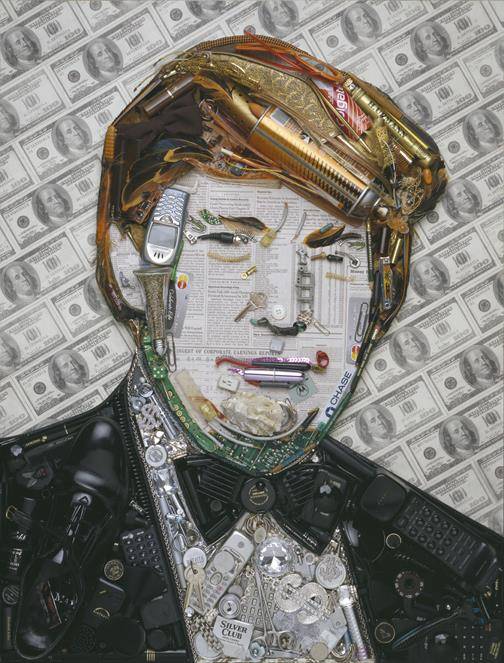

[caption id="attachment_67833" align="alignnone" width="504"] “Donald Trump,” by Jason Mecier[/caption]

“Donald Trump,” by Jason Mecier[/caption]

Meanwhile, a report by the Hill noted that the new administration will follow a scorched-earth budget blueprint, published last year by the Heritage Foundation, that calls for the privatization of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the outright elimination of both the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The good news is that California artists along a wide horizon of styles have been rallying and organizing.

- In December, a group of Bay Area-based artists, writers and cultural producers launched 100 Days Action, an online forum and calendar of daily activist and art-driven activities proposing a “counternarrative” to the 100 day plan that Trump outlined during his campaign.

- In Los Angeles, Hollywood’s World of Wonder Storefront Gallery counter-programmed the Trump inauguration with a show of transgressive protest art called “Surviving Trump: The Art of Resistance,” featuring new works from a roster that includes Ginger (from the activist collective INDECLINE), Kenny Scharf, Raja, Pandora Boxx, Trevor Wayne, Jason Mecier, Sham Ibrahim and media critics the Kaplan Twins.

- Shepard Fairey offered free downloads on his Obey Giant website of his “We the People” portraits celebrating America’s multicultural and racial diversity. The new images turned up on placards carried by thousands at the Women’s March on Washington and offered a human face to those affected by Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda of mass deportations, a border wall and an indefinite ban on Syrian refugees.

Art’s greatest power is its ability to articulate that which is literally unspeakable. And countering the brutalism of the new Performance Artist-in-Chief may demand an artistic resistance that goes beyond galleries or the conventional rhetoric of the demonstration march — or, as Yoko Ono famously phrased it, art that is a verb rather than a noun.

For a sense of what that verb may look like, Capital & Main spoke to two California artists working in the medium of what has been called “social practice” art, a participatory, multidisciplinary medium that uses social engagement and collaboration in works that transcend traditional categories of art and political activism.

San Francisco artist and media designer Amy Franceschini’s roots in farming, environmental and food sovereignty issues have been central to Futurefarmers, the renowned San Francisco-based art collective she founded in 1995. Raised in California by divorced farmer parents — her father was a large industrial grower and owner of a pesticide company in the San Joaquin Valley, her mother an organic farmer and activist near San Luis Obispo — Franceschini is no stranger to ideological divides or food politics.

That formative insight not only shaped Futurefarmers’s political focus, but it informs a collective practice in which members bring their distinct skill sets to bear in socially engaged work that has ranged from "Victory Garden," which transformed the front of San Francisco’s City Hall into an urban farming demonstration garden, to "Soil Kitchen," a wind-driven neighborhood soup kitchen that offered free soil testing to low-income Philadelphia residents. Currently the collective is mounting "Seed Journey," an international sailing expedition organized around the preservation of natural seed stocks, information about the dangers of GMOs and as a resistance to the privatization of the public commons.

"Seed Journey" may be the group’s most explicit rejoinder to the unbridled privatization behind the Trump agenda. The focus of the sailing expedition, which completed its first leg from Oslo to Antwerp in the fall and will begin its second leg from Antwerp to Istanbul in April, is the disappearing of the commons due to the privatization and corporate ownership of knowledge and the importance of preserving the public domain.

Franceschini, who doesn’t like the label social practitioner, describes Futurefarmers’ work in terms that sounds like a cross between conceptual art and political organizing. When the group accepts an invitation to create a work in a new city, she explained, they first investigate the local ecology of political and artistic relationships — who’s working in local grassroots movements, where the anarchist book store is and attending local art openings.

Futurefarmers constructed a rusticated windmill on top of an abandoned diner in North Philadelphia that generated enough electricity to power lights on the ground floor. The windmill was an homage to Cervantes’ "Don Quixote" and the tilting at the windmill that both commented on the green energy future of Philadelphia even as the temporary installation operated with the city on a grassroots level.

“We were able to work with the Environmental Protection Agency, the mayor’s office, local farmers, and create some demand, because our public artwork was commissioned by the mayor as a call to imagine a green Philly in 2015,” she reflected. “The EPA actually took on our model and traveled it to different cities.”

On board the sailing of "Seed Journey" will be seeds “rescued” from the Siege of Leningrad during World War II, going all the way back to Viking-era Finnish Rye seeds recovered by archaeologists from a site in Hamar, Norway.

“Seeds are a beautiful metaphor,” Franceschini explained. “Literally and metaphorically they’re shared through many hands, and so what we say is, ‘How do we keep the power of our commons in the hands of many, rather than the hands of few and, in the case of seeds, in the hands of fewer and fewer huge companies?’”

At the opposite end of the social practice spectrum is Los Angeles multidisciplinary “life-artist” Jennifer Moon. Since emerging as a breakout star of Los Angeles’ Hammer Museum’s "Made in L.A." biennial exhibition in 2014, Moon has become a wildly whimsical crossover attraction in group political art shows on both coasts, most recently sharing the bill of the 31-artist "S/Election: Democracy, Citizenship and Freedom" exhibition at East Hollywood’s Municipal Gallery.

[caption id="attachment_67822" align="alignnone" width="667"] Jennifer Moon, “You Can Kill My Body, But You Can’t Kill My Soul,” 2013 (Photo: Patrick Connor)[/caption]

Jennifer Moon, “You Can Kill My Body, But You Can’t Kill My Soul,” 2013 (Photo: Patrick Connor)[/caption]

Even though her work doesn’t deal in conventional direct-action politics or Futurefarmers’ brand of policy-focused social engagement, Moon sees the election of Trump as an opportunity for politically progressive artists.

“Before the election,” she declared, “people were asking, ‘What happens if Trump gets elected?’ I told them, ‘Maybe the revolution can actually happen then' . . . I hope artists — including myself — do start thinking, Who I’m in partnership with? Why am I making art? Who is this benefiting?”

Moon’s highly autobiographical blend of political theory, psychotherapy and elaborate fantasy explores the idea of love as a revolutionary force — a mix of lived experience and activism that she calls “The Revolution.” Through performances, videos, manifestos and sculptures that playfully draw from the ideas and postures of theoretical physics, cognitive science, self-help gurus and TED talks, Moon undertakes, through her own highly idiosyncratic framework, the very serious business of challenging the underlying belief systems and political economies that perpetuate problems like economic and social inequality, climate change and the depletion of resources.

“My tagline on my website is ‘Jennifer Moon, artist, adventurer and revolutionary,’” Moon explained. “To me, popular politics, which is where Trump exists, is not a form of [authentic] politics in terms of how Hannah Arendt talks about the polis, which is a sphere of freedom.”

Moon’s recent work borrows heavily from quantum mechanics and cosmological theory — how 95 percent of the universe consists of unknown forces and matter that can’t be seen or observed — to explore the tenuous connection between systems of belief and the real world. In 2015’s "Phoenix Rising: Part 3: laub, me and the Revolution (The Theory of Everything)" at Los Angeles’ Commonwealth and Council art gallery, Moon illustrated that fraught connection with an outlandish installation that melded fantasy with the language of self-help cant and included a room-size model of the Large Hadron Collider cobbled from Popsicle sticks, duct tape and Habitrail tubes.

The shared “five percent reality,” as Moon describes it, represents a kind of conceptual prison that ultimately enabled white women and Latinos to ignore to Trump’s attitudes toward women or immigrants in order to cast their vote for him.

“What we’re seeing is not everything that’s there,” Moon explained. “I’m interested in how to access the things that we can’t see as a way to point towards expanding our reality beyond the five percent reality. . . . If I’m really affected by Trump, my job is to go in and identify what he represents, because he’s essentially a carrier of a certain belief, or bad beliefs.”

Shares