Eloquence is essential to the cultivation of constructive citizenship and the emergence of productive leadership. It is not coincidental that the window dressing of America’s current moment of structural decay is the degradation of language. Barack Obama, for eight years, performed his role as communicator-in-chief with an elegant array of rhetorical mastery at his disposal, from the pithy phrase to the professorial dissection of a sensitive subject.

President Donald Trump suffers from such a limited vocabulary that he can describe everything in only the most extreme terms, regularly misspells common words on Twitter -- his preferred medium of truncated communication -- and has made our national discourse resemble a middle school reading of a "Beavis and Butt-head" transcript. The debasement of language is not only influential but instrumental in the decline of political and cultural standards of belief and behavior.

Recently, I had the pleasure of spending a day in Chicago -- capital of American “carnage” -- with one of the most eloquent men in the country, Michael Eric Dyson. He described eloquence as “the performance of a rhetorical gesture to heal.” Providing as examples FDR, JFK, Churchill, Lincoln and even Reagan, he said, “Eloquence is essential as leadership in the face of suffering and assault.”

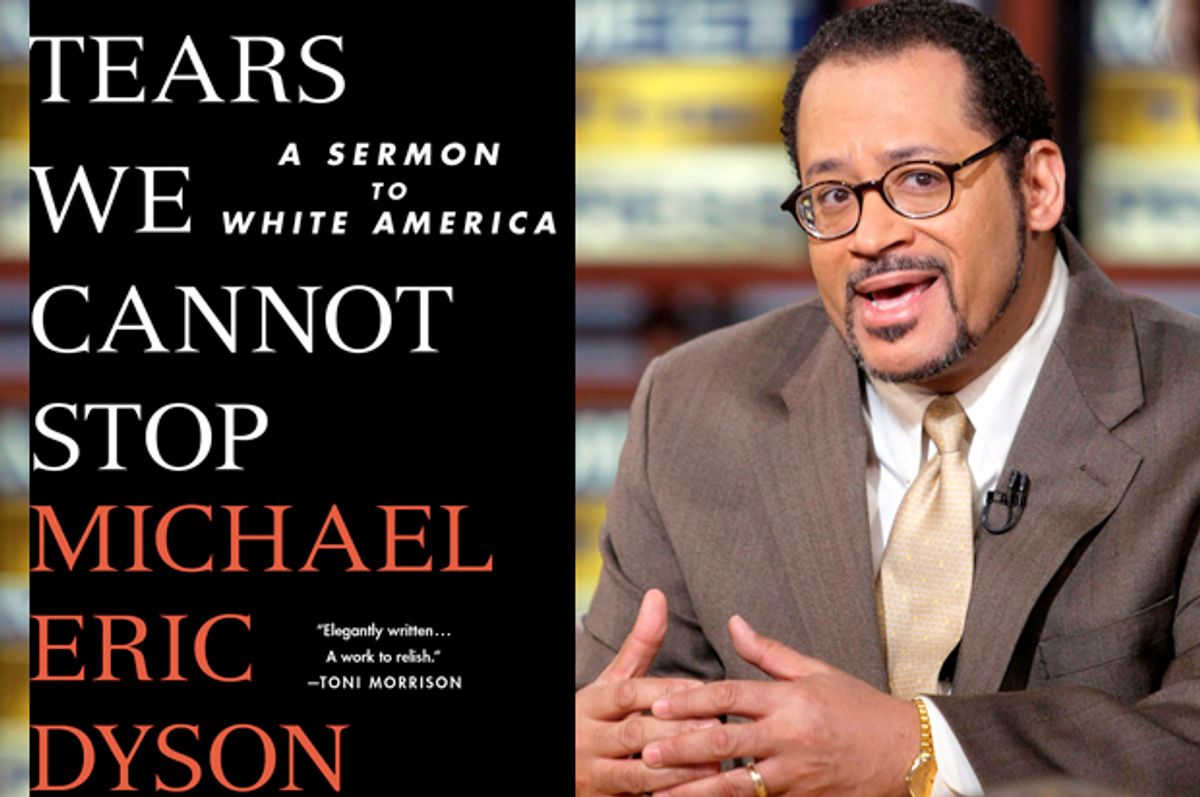

An oratorical acrobat himself, who, in the words of a friend, seems to “have a brain on the tip of his tongue,” Dyson is tearing up his shoe leather and wearing down his vocal chords to promote his new book, "Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America." It is a pugilistic but poetic book of both confrontation and sympathy. Like every radical message, its own is simple: “White Americans are always telling black Americans, ‘Stop being black, just be American,'” as Dyson explained it, “Well, I’m here to say, ‘Stop being white, and just be human.’”

I first discovered Dyson’s boundless body of ever-expansive work when I was in high school. His writing on politics, race, religion, music and sexuality became inspirational and foundational to my development as a writer, and a human being. Like a police flashlight on a suspect hiding in a hole, it also illuminated the lie of white supremacy. In content, Dyson explained black achievement even in the midst of vicious institutional and individual racism. In form, Dyson demonstrated black excellence. From Martin Luther King to Tupac Shakur -- two subjects of brilliant Dyson biographies -- African-Americans have elevated America’s literary and rhetorical traditions, and in doing so created soulful and cerebral models of communicative citizenship: citizenship that speaks, offering instruction for public and private conduct.

In an unintentional and profoundly postmodern act of self-sabotage, white voters have allowed the nation to slip out of the hands of Barack Obama, the Elvis of American oratory in the 21st century, and into the cold, lifeless grip of Donald Trump. It is impossible to imagine a better illustration of how common white beliefs about their own intellectual, emotional and moral superiority are laughable.

Dyson calls Trump “America’s first toddler president,” adding, “with no offense intended to toddlers.” “Trump is the most amazing example,” Dyson said, “of the willful refusal to grow up, mature, develop and evolve.” It was not even subject to debate among many Republicans during the primary that Trump is self-consumed, given to tantrums, and transparently insecure in his egomania. He is also, according to Dyson, “the most hideous face of willful white innocence.” As if it were an occupational duty, Dyson announced, “It is my job to associate Trump with whiteness.”

Willful white innocence is the ongoing ability to maintain guiltless and blameless posture and ideology. It is absurdist theater, but as Dyson contends and countless examples indicate, “it is threatening to the nation’s moral and patriotic health.” It is also closely connected with “white fragility” -- “the belief that even the slightest pressure is seen by white folk as battering, as intolerable, and can provoke anger, fear, and, yes, even guilt.” Dyson writes these words in his new book, presenting a civic homily for harmony, but a harmony that emanates out of honesty. Reconciliation is not possible without recognition. Simple recognition is one of Dyson’s demands for white America. Willful white innocence and fragility, however, refuses to recognize. It interprets the rallying cry “black lives matter” as exclusionary and hostile to whites, and it views the relatively trivial act of a quarterback taking a knee during the national anthem as an attack against the emotional center of white life.

The white soul as an exposed nerve ending is predictable, because as the first line of Dyson’s sermon states, “There is no such thing as white people.” Genetics have proven that race is a social construct, and that dividing people according to skin color is as legitimate as creating a sociological category out of eye color. Despite its biological fiction, it remains a social fact. In a pastoral service of compassion, Dyson argues that white Americans are also among the victims of the invention of whiteness. “It is most effective when it appears neutral, human, American.” It is also a burden to carry. Like the rejection of Black Lives Matter in the contemporary context, it is historically amnesiac: “You embrace history as your faithful flame when she kisses you, and yet you spurn her as a cheating mate when she nods or winks at others.”

“We’re always told to get over slavery, because we ‘aren’t around back then,’” Dyson said in Chicago, “Well, we aren’t around when the Constitution was written, but we all benefit from it. Do we need to get over that?”

Black people are always told “get over” race altogether, but the painful irony is that their admonishers are the ones who most benefit from race, at the same time that they are blind to it. The contortionist ability of pundits and politicians to make the election of Donald Trump about everything but race is but another piece of powerful evidence. Dyson does not expect Trump voters to read his book -- they would probably sooner burn it -- but he does want to reach white liberals who refuse to take into account the pernicious and pervasive consequences of the color line. How many commentators have remarked, without self-awareness, that Trump’s victory demonstrates the need to get past identity politics, so that Democrats can begin to once again appeal to the white working class? Donald Trump is the most powerful practitioner of identity politics in the world. But he is not alone.

The first Democratic leader to announce the death of identity politics, and intentions to appeal to the white working class, as if “white working class” is not an invented category inhospitable to black, Latino, Asian and Native American working-class people, was Bernie Sanders.

“Bernie Sanders is the left-wing version of Donald Trump,” Dyson assessed, “Not in terms of ideology or politics -- that’s ridiculous. I would ride with Bernie all day long, but they are elderly white men who evince no substantive ability to engage race at a profound level. Both of them rush away from the specificity and particularity of blackness, and in Bernie’s case, would rather subsume race under class. That’s a mistake.”

Dyson then recalled that Derrick Bell, the originator of critical race theory, once told him a story about Communist recruitment in Harlem. The Marxist-Leninists promised to change everyone’s life with a revolution of the proletariat. An old black man looked at the recruiter and asked, “After the revolution comes, are you still going to be white?”

“There is a brand of animus that can survive social revolution,” Dyson said to punctuate the story. He then lamented that “the degree that anti-black animus has penetrated even enlightened leftist circles is tragic.”

Dyson also cautioned against the brand of moral complacency that reserves condemnation for the Trump coalition. “We all helped create this,” he said. “Frankenstein is the name of the doctor, not the monster. It is the system that produced Donald Trump; stitched him up from the discarded parts of ideology and party. He is the roaring manifestation of white rage.”

So where is American culture to go in a new moment of political terror when black citizens must navigate one side that is contemptuous of them and another that is too often indifferent?

Shelby Steele, a leading black conservative, has classified black leaders as “bargainers” or “challengers.” Bargainers attempt to ingratiate themselves to whites, and avoid confronting them on issues of race, in order to exact something they want in return. Challengers are directly combative on racism, demanding that whites make concessions.

Dyson believes that, for ceremonial, political and persuasive reasons, Obama attempted to bargain with white America. To a fault, he avoided race in public discourse, and even dodged making direct commentary on Trayvon Martin and incidents of police brutality until he felt he had no other choice. His obvious and rather mundane observation about Martin -- “He could have been my son” -- set off a firestorm of white anger because it violated the bargain. A simple, superficial statement challenged white assumptions and anxiety.

“You can’t coddle white brothers and sisters,” Dyson said, in rejecting the Obama approach of diplomatic delicacy. “I believe they are adults, and they can withstand the truth.”

“The truth shall set you free,” as the Bible declares, and with his new book, Dyson settles into his role as ordained Baptist minister to deliver a civic sermon to the entire nation. Bargaining, placating and soft-selling summoned Donald Trump. It is time for challenging. It is also time for art.

A great book, just like an effective sermon, is a work of art. With "Tears We Cannot Stop," Dyson beautifully blends the two forms into one cohesive package of introspection, political provocation and spiritual redemption. Rather than thunderously damning the readers, he injects humor, personal confession and self-criticism as mechanisms of balance. He is just as hard on black Christians for their homophobia as he is on white Americans for their bigotry.

“I am not making pronouncement with the gaze of God,” Dyson explained. “I am, in the words of Wes Montgomery, ‘down on the ground.’” He promises to speak and write with a “worm’s eye view,” providing “revelations from the dirt of human experience.”

In the parlance of old preachers, he wants to “put it where the goats can get it.” Dyson has made his work accessible in the aim that whites and blacks can come together in a bond of solidarity, but only if it is the “solidarity of truth.”

Accessibility is not vulgarity, however. The artistry of Dyson as essayist and minister is on dazzling display throughout this text. He writes with the rhythmic quality of music and poetry, creating a work that is subversive in its message and medium. The desperate need for melodic breakthrough into the cacophony of racial ignorance is obvious in the age of Trump. Also necessary is the elevation of America’s civic vocabulary and national dialogue so that its audience and amplifiers can both find common ground on the higher ground. Instead of crawling in the gutter with Trump, they might reach for the rooftops.

At a time of Twitter and Trump, when too many people prefer punchy phrases to sustained reflection, or relate to the president’s reduction of political language to street-side taunts, some might wonder about the utility of intellectuals and magicians of rhetoric like Dyson. Do we still need them?

As I sat in a synagogue on the South Side of Chicago, on the same street as Barack Obama’s Hyde Park home, and looked out at a racially diverse and young audience transfixed by Dyson’s entertaining and eloquent lecture, I remembered the campaign slogan of Donald Trump’s forebear, Richard Nixon: “Now more than ever.”

Shares