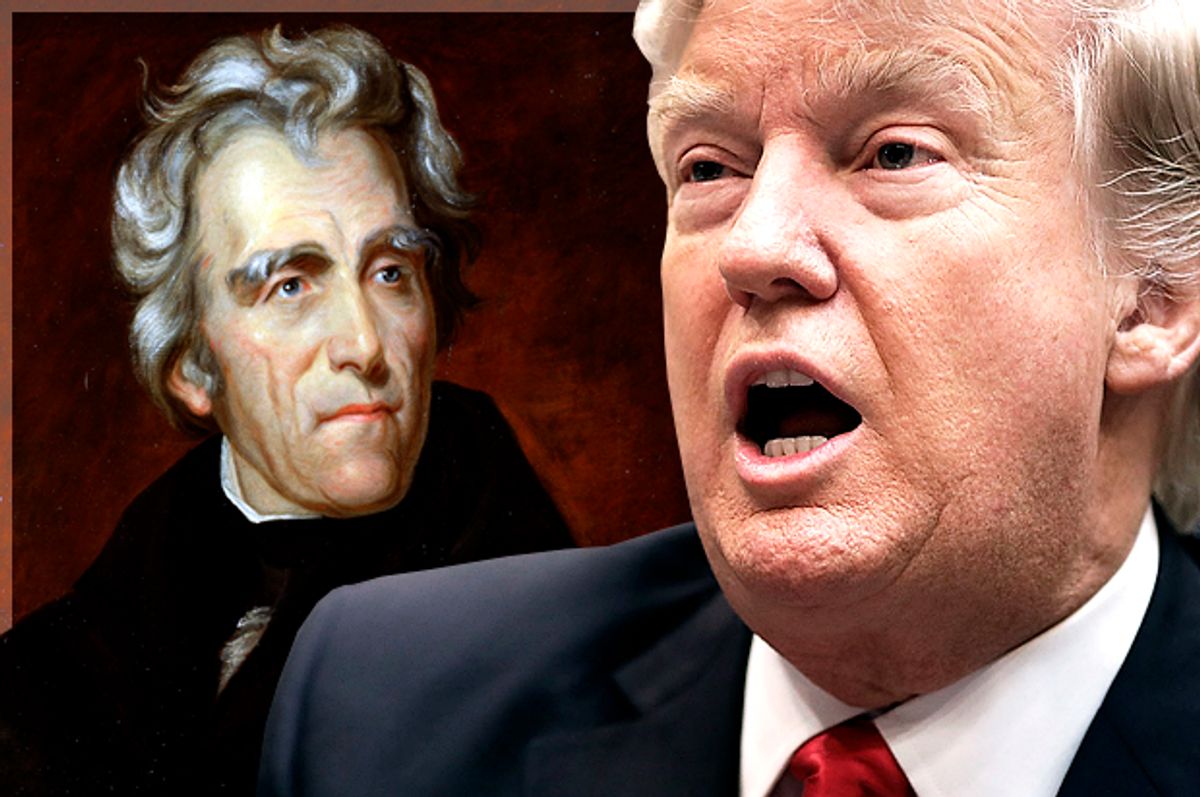

Steve Bannon, President Donald Trump’s resident grand strategist, likens his boss’ ascendancy to the insurgent populism of Andrew Jackson, our seventh president. Like Jackson did, Trump promises to drive a stake into the heart of moribund, elitist politics. Amid a roiling global upset over Trump’s edict barring immigrants and visitors from various Muslim-majority nations, Bannon’s Jacksonian analogy demands our attention.

Naturally, historical comparisons across such different eras warrant caution. They risk superficiality and confusion. America today is a radically different place than it was in 1828. Jacksonian America was heated with expansionist fervor; today we struggle to find answers for our declining global strength. No less important, our democracy is multiethnic, disparate and heterogeneous; its bubbling pluralistic diversity would have horrified Jackson, a man whose populism was starkly homogeneous. His vision of democracy was for white men only.

No less striking are the enormous personal differences. Jackson grew up dirt-poor. He rose by dint of guts and grit to become a lawyer, politician, judge, general and finally president. His remarkable political celebrity rested on accomplishment, experience and sacrifice — albeit more the sacrifice of slaves, women and Native Americans than his own. He was, in Jon Meacham’s words, “the consummate self-made man” — at least as much as any master of slaves might claim to be “self-made.”

Donald Trump crashed into public view by dint of his father’s wealth, privileged access to capital, and a facility for feeding the media's appetite for blooming, boisterous egos. For his country he has sacrificed nothing.

Yet for all such differences of history and biography, Bannon is not completely off base. There are similarities. Each man defeated a champion of the elites: Jackson bettered no less a figure than former president John Quincy Adams. And like Trump, Jackson regularly displayed boundless self-confidence. As historian Steven Hahn has reminded us, by the time he became president, Jackson was a rich man “deeply suspicious of any authority other than his own.” This is all eerily familiar. But more ominous resemblances also deserve our notice, especially calls to white male resentment.

Andrew Jackson dedicated his military and political life to America’s expansionist project. As both a military leader and president, he had the goal to ever to enlarge the American territory. He believed white men needed room, much more room for plantation slavery, land speculation, farms and settlement. Expansion was the route to American opportunity, the path to its greatness. It was the dynamic behind the promise of white men’s equality.

Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed that Americans were “born equal.” Jackson knew better; he certainly wasn’t born equal to a president’s son. Equality for poor white men like Jackson was anything but Thomas Jefferson’s “self-evident truth.” Thick layers of privilege and power divided early 19th-century America between the many and the few.

For ordinary white men to know equality, they would have to struggle for it, forge it through action. Battlefield service, such as Jackson’s, became one qualifier of white male citizenship. But more was needed: White men had to insist upon political recognition and dignity from elites reluctant to confer it. They needed a loud political voice and effective power, mobilized and equipped with the energy, leadership, organization and discipline to rattle the establishment. They needed machine-like politics.

It took an agonizing defeat in 1824, Jackson's first presidential campaign, to teach him that lesson. Old Hickory won a plurality of the popular vote for president that year, albeit barely 40 percent. But in a deal that Jackson famously labeled a “corrupt bargain” — an advance echo of Trump’s “rigged system” — Adams took the Electoral College vote and the White House by winning senator Henry Clay’s support in exchange for an appointment as secretary of state.

Burning with resentment but channeling it with skill and dedication, Jackson labored with a handful of well-placed followers in New York and other key states to build a new political organization that would soon emerge as the nascent Democratic Party. Boring deep into neighborhood precincts, where the voters lived, Jackson’s followers corralled support, appealing to angry white men resentful of paper money and class and elite pretension, as well to land-hungry speculators and patrician slave masters. Four years of hard political labor brought them a resounding victory in 1828.

With Jackson’s aggressive leadership, they could now bulldoze through the second national bank, overcome restricted public land sales, defeat the anti-slave doubters and dislodge Native American opposition to open wide the gates to new lands for settlement, speculation and, of course, for slavery. Jackson promised to establish a broadening economic foundation for white male equality and dignity. These would arrive with his militant, expansive, often-violent agrarian democracy. C. Wright Mills described it well: a rough-hewn democracy of “one rifle, one vote.”

Jackson’s gun-toting democracy resonated perfectly with his discordant but cooperative band of brothers: slave owners aggrieved by absentee banks; land speculators looking to make a killing; small farmers on the hunt for cheaper, more productive land; and anxious urban workers, especially those who labored without respect in the great port cities of the East and South. What bound their political allegiance to Jackson was his genuine regard for their standing as equal white men, plus his intolerance of any institution or policy that inhibited westward expansion and the national power to drive it.

No transgression would be tolerated against the popular white freedom to take and develop more land. Native Americans would be removed — and slaughtered if necessary. Nicholas Biddle’s national bank of the United States, for all that it was mixed up in the sordid finance of slavery, would not be permitted to centrally regulate credit or stymie speculation. And despite Jackson’s slave ownership and stalwart sympathy for “the peculiar institution,” not even Southern intransigence would be permitted to weaken the nationalizing project. When radical South Carolinians dared to nullify Congress’ “Tariff of Abominations,” Jackson stared them down, drafting a muscular defense of national supremacy.

In all these ways, Jackson’s national populism expressed the thrust of a new, often bloody mass democracy. It was, for all intents and purposes, as Edward Baptist has written, “a new kind of government. Not a dictatorship, not a republic, it built white men’s equal access to manhood and citizenship on the disenfranchisement of everyone else,” most notably Native Americans, enslaved African-Americans and women.

Jackson’s was a definitively white nationalism, a racialized, gendered populism and a homogenized democracy. And its force was enormous. It not only pulsed west and south, but downward, ever downward, its exclusionary force falling on the straining backs of those who labored and lost “without just compensation.”

Steve Bannon expects us to ignore the ugly, depraved and violent facts of Jacksonian history. But in selecting Andrew Jackson for his Trumpian model, he calls to mind inexpungible stains of oppression, bloodstains that form a key part of its historical truth. But Bannon also calls forth an imperative to oppose its revival. As the nation and the world ponder the effects of Trump’s immigration policy, it is worth recalling what Nazi theorist Carl Schmitt said of this brand of democracy: It “demonstrates its political power by knowing how to refuse or keep at bay something foreign and unequal that threatens its homogeneity.” The handwriting is on the wall.

Shares