This isn't the first time in history that people who call themselves Christians have been doing awful things. It isn't the first time many of us who still seek meaning in our faith find ourselves questioning what our belief system truly stands for in the real world. Yet it feels a particularly acute moment nonetheless, one in which the need to speak out against hypocrisy and injustice is stronger than it has been in recent memory, and when the temptation to bail on belief seems on many days awfully appealing.

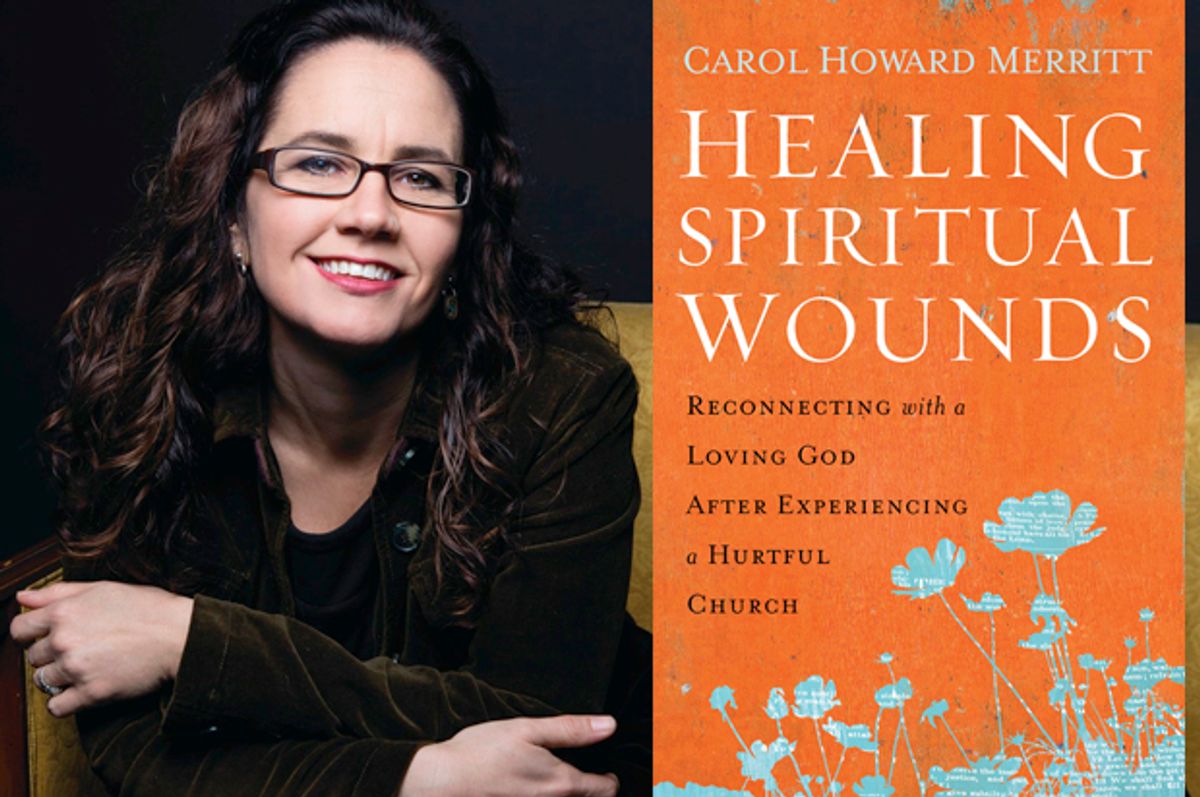

Author and minister Carol Howard Merritt understands. In her deeply personal, refreshingly honest memoir/guide "Healing Spiritual Wounds: Reconnecting with a Loving God After Experiencing a Hurtful Church," she delves into her own difficult past in a strict Christian household, and her own hard-won lessons in practicing a more conscious Christianity. Merritt isn't out to sell spirituality to anybody who doesn't want it. Instead, she's clear her book is aimed at those who, like her, have seen some of the worst aspects of the institution yet also can't deny that they "see the world through an irremovable religious lens," because they can't deny having a "spiritual or theological orientation."

I'm a skeptical, often frustrated Catholic. I have lately been struggling with my own frustration at the face of American Christianity while simultaneously looking hard for answers in the best examples I derive from my faith — justice, mercy, compassion and outspokenness. That's why Merritt's book has been so welcome — it's a timely template for personal reflection, and for reconciling the quest for spiritual fulfillment with our deeply flawed institutions and the people within them. Salon spoke with Merritt recently via phone about keeping the faith.

I was really impressed with the book as a Christian myself, a Catholic, working within a very complicated institution, one that would not give a woman the same kind of career opportunities that you’ve had.

One of the things that you say right from the beginning of the book is that this is not trying to persuade people who don’t want to be persuaded. It’s for those of us who have that part of ourselves that just always comes back to the spiritual path, and need to reconcile ourselves with that. What made you want to talk about that, and what made you want to explore Christianity for the spiritually unreconciled?

I grew up going to, or looking at, the Billy Graham crusades, where people would pile down to accept Jesus Christ into their hearts. I would look at these things and think about the people still on the benches. How did they feel? I’ve always been drawn to those people, the people who aren’t rushing down to accept Jesus Christ into their hearts. What’s going on there? I suppose it’s that vulnerability that I have in my own life, a constant struggle of knowing how the church wounds, but also understanding how it heals. I’m just drawn to that person, the person who is trying to be an atheist but keeps backsliding, who can’t help but pray when they want to not pray.

Especially in this particular climate, I am very aware of how I can behave as a Christian, and be sensitive of the fact that Christianity is now becoming such a political agenda. Christianity is part and parcel of an agenda that is being used to really punish disenfranchised people.

Absolutely. There's just all this hate and venom that’s being used in the name of God. As a Christian it’s so hard to see it. It just feels like a punch in the gut to something that in its best ways teaches us to be fully human, fully alive and fully who we are as men, women, gay, straight, transgender. Christianity should keep us alive to these things, and yet it’s being used to discriminate and to allow hatred.

A lot of us have something like that in our experiences, where we’ve heard the message coming from a Christian leader that just seemed completely the opposite of the message we were getting from Jesus.

It’s like there is this toxic stream and there's this healthy, life-giving stream, but they’re together in one river, these two streams. Many times for us, especially if we've gone through these particularly wounding experiences, we have to learn how to be able to siphon out that life-giving, healthy water and learn how to drink of that somehow.

When people ask me about my faith and why I still call myself a Christian, I always compare it to how I feel about democracy, how I feel about my country. I love my country, I love America. A lot of horrible things have been done in the name of this country, a lot of things I vehemently disagree with, but the founding principles are what sustain me and there’s a distinction.

Your book is not just a memoir, it’s also a specific action plan. How did you balance that in the writing of the book?

Part of it was getting the right frame around that story and I wanted to talk about this intersection between how religion hurts us and how religion heals us.

How do we move forward in the world in a public way, where we’re trying to reconcile our own relationship with faith and this perception of us as — I think for a lot of people — the bad guys right now?

Mainline Christians and social justice Catholics and liberal, historic black congregations, putting those together, they far outweigh evangelical Christians — and particularly conservative evangelical Christians — who are tied up with the religious right. But often times people’s perception of Christians is from a very small extremist group that really cares about the oppression of other groups. It’s a difficult fight because we have to reclaim who we are, and we have to reclaim a lot of our language in the public square. It’s difficult because I think in the words of Anne Lamott, she would always say she's a Christian but not that kind. So it feels like that. I find myself saying that over and over again — not that kind of Christian.

In some ways I feel it’s a really hopeful time for people who care about those who are sleeping outside, people who care about poverty, people who care about peace making. Because all of a sudden we’re united in a way that we were not before. It feels like there’s more of a compelling voice that’s coming out of this group because of the resistance, that we’re having to really make ourselves known. I really care too in the midst of this, because there are a lot of evangelical Christians who woke up the day after the vote and just said, I can’t do this anymore. I can’t be evangelical anymore and everything that I love about being evangelical has been taken away from me. So, I really hurt for them and hope in some ways they will be able to have a more life-giving, abundant faith.

I think the first step is, you have to figure out, what is my Christian identity? For a lot of us that's unraveling some of the damage, and the wrong messages, and the hurt and, for many people, abuse, that has happened first. And working from that, how do you figure out what your definition of a merciful and loving and protecting God is? That’s hard work.

It’s all very difficult work and painful and I think writing this book was a lot more painful than I expected it to be. You’re wrestling with these things that you’ve grown up with, that really formed you, and there are two things happening. You have to look at them and say, "Does this belief correspond to a loving God? Is my image of God a loving God? And if not, I have to get rid of that." But at the same time you have to be gentle with yourself because for years and years I would always think back and think, "How did I believe that? I’m such an idiot. I was so stupid." Of course, it was not getting me anywhere, me thinking of myself as an idiot. What helped was when I could finally say, "You know what? I believed this thing and this thing helped me to gain the connection with my parents. It helped me to gain approval from a community of faith. It helped me to have a basis of morality even though I don’t necessarily agree with that basis now." I should be able to uphold myself and understand that I was doing the best I could.

Practicing self-compassion and self-forgiveness is also a really hard thing to do. I think a lot of people turn away from faith even when there’s a part of them that still really feels attracted to it and really feels compelled toward it, because it’s easier to just reject it outright than to sit in this sometimes very uncomfortable relationship.

I think it’s important for us to deal with these things. To put them out on the table like, listen we’ve screwed up, we were terrible. For my denomination I remember I became an adult during the AIDS crisis, and Christians were terrible with that. They were awful, and here people were dying and they were finding community in amazing ways, and they were taking care of each other, and they were loving each other, and the loudest most obnoxious voices were saying — it’s hard to say out loud — but they were saying this is what they deserve.

What would you say are some first basic steps for someone who maybe is completely disconnected from a community of faith, maybe has nobody else in their lives who’s thinking about Christianity in a non-negative way? How do they then take that first step walking toward the direction of something that feels spiritually comfortable?

Jesus talks about how all the law is summed up in loving God, loving your neighbor like you love yourself. I think that is crucial for how we get to spiritual healing in the sense that it needs to be a loving God. So, often times spiritual harm has been caused because we imagine God is angry, and vengeful, and we imagine that there could be a God who would punish people with AIDS -- and that is not a loving God. It just doesn’t make sense that God would form us from the dust of the earth and breathe life into us and then say, "You’re all going to hell."

It feels really counterproductive. I’m not God, but that does seem really like a silly plan. That’s not how I would run things.

So, being able to think of God as loving is really important, and then loving yourself. If you’re a woman and you’ve been told that you have to submit, or if you’re gay and you’ve been told that God abhors you, or if you are transgender and told all of the terrible things that we tell people, take those messages and understand that God loves you and you can love yourself. Love yourself no matter what your gender is, no matter what your ethnicity is, your race, your sexual orientation, your gender identity. God loves you, and understand that you can love yourself. Then the idea of loving your neighbor to me is a very outward social justice system. You’re loving your neighbor as you love yourself. That means you’re thinking communally. You’re thinking about how to embrace this or you’re thinking about disparities between the rich and the poor and you’re thinking about all of these things in a much broader sense.

When Jesus said to love your neighbor as you love yourself, he wasn’t living in a white gated community. He was living in the Middle East. We should be loving people as we love ourselves, and that doesn't just mean that we love Christians as we love ourselves, that we love people who think like us or act like us. We should be a loving society.

I like that you really talk about fear and how any system that is playing on your fear as opposed to your love is just inherently going to be warped and inherently going to be harmful. This is something that I’m certainly working on a lot lately — how do we move away from fear when there are legitimately things to be afraid of, to not see that fear as something that God wants for us?

Yeah, this I learned from reading neurologists who study thought and prayer. They made this neurological connection that if we are afraid of God then that little bit of our brain gets triggered and the anger and the fear is all tied up in this ancient part of our brain. As we move to spiritual wholeness it’s really important to be aware of where we are in that. Are we feeling fearful? People have a reason to fear right now, they have a reason to be protective with their bodies and that’s part of loving themselves. But when we allow our anxiety to get wrapped up in the rush of social media, or the rush of fear of violence, or the rush of the fear of a terrorist attack, we have to begin to breathe and meditate and think about how that fear or that anger is affecting how we’re acting and reacting.

Again, it’s such hard work. It’s just constant work and for many of us we’re doing this work within our jobs, within our health situations, within parenting. It’s a lot to add to the plate and I think that’s another part of why people kind of get turned off to spirituality, because it asks a lot of us. It asks us to do things, it asks us to work, it asks us to really reflect on ourselves, and our place in the universe, and our place in society, and our place in our community, and what community looks like. But when you do that maintenance on the regular and you find what works for you, and what clicks for you, and for many of us that is Christianity, then you can at least start your day somewhat more armed, somewhat more shored up for then whatever comes along. It’s very challenging.

I mentioned in the book about having shattered lives. Often times we walk around with these pieces of our lives shattered all around and it takes a long time to sit down and intentionally bring those pieces back together, imagining who God is, being intentional about acts, praying, learning to pray again. I was talking to a person who is AA recently and he was saying that they always get to this step where you have to reconnect with a God of your choosing. He said he thinks that a lot of people start drinking again because they just can’t get there. They can’t articulate it, it’s too painful, they can’t move away from the God that they grew up with, and that makes sense. These are things that are intimately entwined with who we are and our being and so for a lot of us, changing the way we see religion or changing the way we interact with God in our life, it’s not like you’re closing one door and opening up another. It’s just struggle.

This is a time where people feel really bad about religion and a lot of people are yearning for a spiritual life and longing for connection with God. It’s very difficult right now as ugly as Christianity looks in our day-to-day lives. I am hoping that people do find a way to connect. That they’re able to imagine a Christianity that’s disentangled from the hatred and bigotry that it’s being used for right now.

One word that I love that I hope to reclaim is this idea of being born again. As I think about that word I think about, wow, to be born of God means that God has to be feminine. For me as a feminist, I hope that I can begin to talk about myself as being a born-again Christian and that people might imagine the spiritual life force giving birth to me, because it’s a beautiful image. Reclaiming that would be a wonderful thing.

Shares