Every so often the right book comes along at the right time and quite deservedly catches fire. Angie Thomas’ debut Young Adult novel “The Hate U Give” is that book for early 2017 — it’s topical, urgent, necessary, and if that weren’t enough, it’s also a highly entertaining and engaging read.

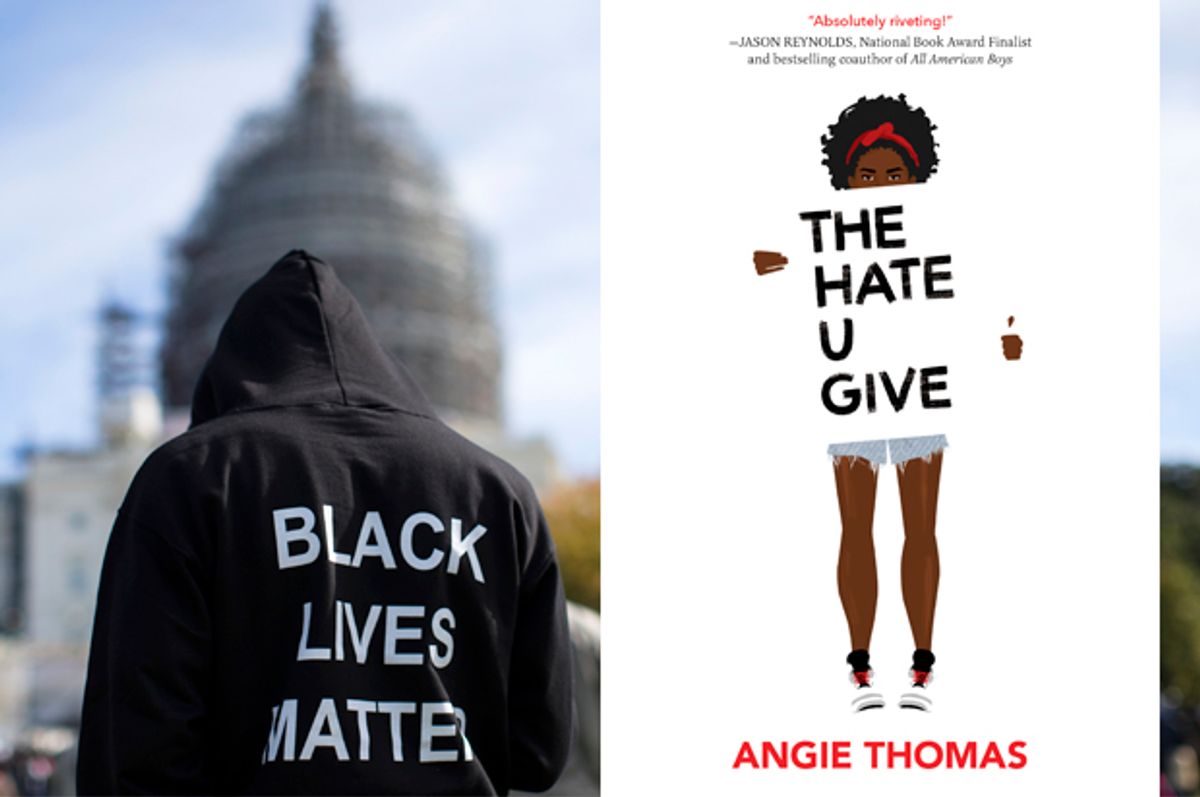

Expectations have been high for Thomas’ book, which is billed as “inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement.” Maybe the most hotly anticipated YA novel of the last year, “The Hate U Give” catapulted to industry prominence a year ago, when Balzer + Bray acquired the manuscript in a 13-house auction for an unknown (but reputed to be in the six-figure range) amount. The announcement that the film was optioned by Fox 2000, with “Hunger Games” star Amandla Stenberg to star and George Tillman Jr. (“Soul Food”) attached to direct, came soon thereafter.

This is not the average response to a first novel from a 20-something writer who is not the product of a prestigious MFA program or the New York publishing scene. Hailing from Jackson, Mississippi, Thomas’ previous claim to fame was, by her own admission, an article about her precocious rapping skills in the now-defunct teen magazine Right On! (Enthusiastic citations of this delightful bio detail have, alas, ruined any chance of Google discovering the actual article in any online archives.)

All of that fuss is well deserved. The heroine of “The Hate U Give” is Starr, a 16-year-old black girl caught between two worlds. Starr lives in a predominantly black and poor city neighborhood but, along with her brothers, attends a ritzy, mostly white prep school on the other side of town. When we meet Starr, she’s at a party with her neighborhood friend Kenya, acutely aware of her learned habit of code-switching and feeling unsure of her place in the local scene. A gang dispute leads to shots fired and she flees with Khalil, her childhood best friend whose path forked from hers when she went to prep school and he started selling drugs. Starr and Khalil have nothing to do with the violence of the evening, but are stopped by a policeman on their way home. The cop shoots Khalil in front of Starr, and Khalil dies.

Traumatized and guilt-ridden, Starr has to decide how she will advocate for Khalil as the investigation into his death plays out, while also deciding how much of her life at home she can reveal to her wealthy school friends — including her boyfriend, who’s white.

Meanwhile, her parents — her mother’s a nurse and her father runs the neighborhood grocery store, which their family owns — are torn between wanting to move somewhere safer and staying on, even as the mother of Starr’s half-brother Seven (and Kenya) lives with a drug lord whose unfinished business with Starr’s father threatens them all. Khalil’s murder fractures the already tenuous peace in the neighborhood. The action of the book, which ranges from novice gangbanger DeVante running for his life to high school Tumblr and Prom drama, comes to a head as the grand jury decides the future of Khalil's case.

So yes, this is a highly topical novel that calls to mind the killing of unarmed black people at the hands of police officers and the subsequent protests and uprisings: Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Alton Sterling, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, and too many others. But it is not a melodramatic 21st-century teen “problem novel.” There are no easy answers in this narrative — in fact, one of the most important people in Starr's life is also a cop.

A novel with Starr at the center is a gift to black girls, who do not every day in this America witness a fierce business war over the privilege to tell a story with a girl who looks like them on the cover, and here’s hoping the book’s success opens more doors to agents and publishers looking for “the next Angie Thomas” and launches Thomas as the next major voice and face of YA. But the secondary tier of potential for transformative power this book holds is its capacity for capturing the imaginations of affluent and middle-class white readers, for whom the residents of neighborhoods like Starr’s are so foreign they might as well live on another planet. They even have their own proxies on the page — Chris, Starr's good-natured white boyfriend who wants desperately for her to let him in and trust him with her problems, and Hailey, her Queen Bee school chum who would rather pretend that All Lives Matter.

Every clueless white person on Facebook who commented on a story about the Baltimore uprisings with "but why are they destroying their own neighborhoods?" should be required to read this book. White people who have only seen poverty from a vague distance need to read this book and talk about it at home. White people who pull away from their black friends when they want to talk about racism should read this book and write a full report, with proper MLA citations. White people who have no black friends should at least make their book clubs read this book. The entire police force of Catlettsburg, Kentucky, should not only have to read this book, they need to each buy five copies and give them to their white friends. Donald Trump, who knows so much about black neighborhoods, should read this book (but it’s written on a high school level, so don’t hold your breath). Mel Gibson should have to send a copy of this book to every high school library in the country, and Australia too.

This is not to cast "The Hate U Give" as a punishment reading assignment. How can it be with Starr, who is low-key hilarious when she's in social observational mode, at the center? But because Thomas works diligently to make the reader feel empathy for all of her characters — not only for Starr, who makes many age-appropriate mistakes, mostly out of fear, but overall is a likable sneakerhead with a totally meta fondness for the vintage sitcom "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air" — the novel is one big teachable moment disguised as a page-turner. "The Hate U Give" complicates the easy narratives of "drug dealers are evil" and "cops are corrupt" through the characters of Khalil, DeVante and Detective (Uncle) Carlos, and renders secondary characters so vividly and personally that even the mothers who endanger their children and gangbangers are understood, if not pardoned. When the simmering anger and frustration finally boils over in the neighborhood, Thomas makes the reader feel the internal and external turmoil with acute emotional precision.

It might not be possible to dismantle so-called de facto segregation in time to cultivate the kind of understanding among neighbors that proximity creates before the next unarmed black person's name becomes a hashtag, but as neuropsychologist Jamil Zaki says, art can serve as an "empathy boot camp" for cultivating an emotional understanding of how human beings react in circumstances unfamiliar to the observer. This book won't make the systemic needs for Black Lives Matter disappear overnight, but it does have the potential to move the empathy dial in thousands of small and personal ways. I wouldn't be surprised if it becomes a classic of this era, still treasured for its historical context and timeless characters even after, God willing, its theme is no longer relevant to current events.

Shares