Russia hacked the election. Russia didn’t hack the election. Russia sort of, maybe, possibly hacked the election.

Is your head spinning from this story yet?

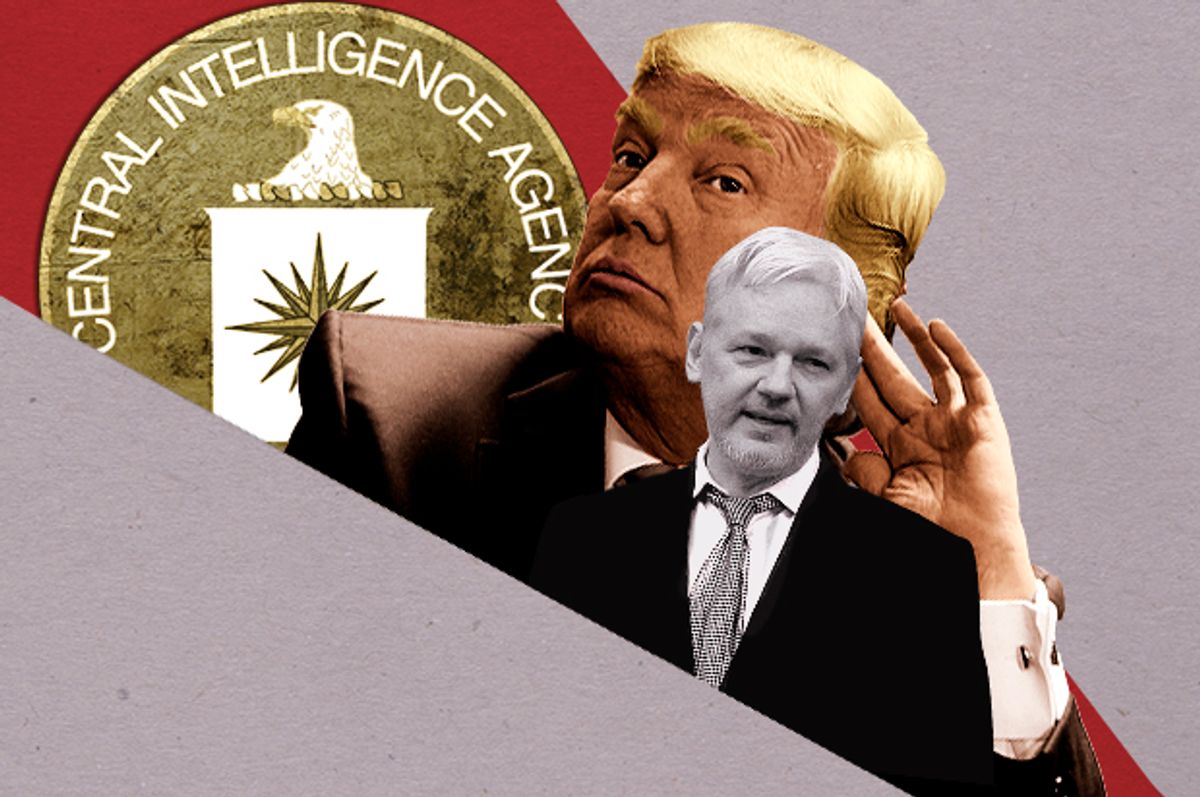

The latest WikiLeaks disclosures concerning the CIA’s hacking abilities has further complicated the hall of mirrors that is the Russian hacking story. The "Vault 7" leaks are believed to be authentic and reveal a few uncomfortable truths about the overreach of U.S. intelligence agencies.

Reactions to the leaks have varied from those who think they could be more significant than the Edward Snowden revelations to those who think it’s all a bit of a non-story. Basically, it’s a pretty clear split between those who regard WikiLeaks’ editor Julian Assange as a trustworthy whistleblower and those who regard him as a tool of the Kremlin.

Among other things, the leaks revealed that the U.S. government is essentially paying out to exploit the vulnerabilities in software without telling companies and, disturbingly, that they could be using your iPhone or Samsung TV as a microphone — even when it’s supposedly switched off.

One of the most interesting disclosures concerns how the CIA can cover its tracks by leaving electronic trails suggesting the hacking is being done in different places — notably, in Russia. In fact, according to WikiLeaks, there’s an entire department dedicated to this. Its job is to “misdirect attribution” by leaving false fingerprints. If you’ve been at all skeptical about the recent levels of Russia-related hysteria, promoted heavily by U.S. intelligence agencies, alarm bells are probably going off in your head.

Keeping these tactics in mind, the evidence presented to prove that Russia hacked the Democratic National Committee in an effort to throw the presidential election to Donald Trump becomes flimsier than it was before. And it was pretty flimsy to begin with.

Recall, for example, that cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike conveniently concluded within one day that the Russian government was behind the attack on the DNC servers. I say conveniently, because the DNC paid for CrowdStrike’s services — and it’s fair to say the DNC had an unhealthy fixation on all things Russia for the duration of the election cycle.

The evidence provided by CrowdStrike included the fact that malware found on DNC servers was the same as malware believed to be used by Russian intelligence units, that metadata files included information in Cyrillic text, and that emails had been sent using the Russian email service Yandex. In other words, it was nothing the CIA couldn’t have done itself in order to “misdirect attribution.” What’s more, CrowdStrike actually admitted that it deliberately left out evidence that didn’t support its claims that Russia was responsible.

FireEye, a competitor of CrowdStrike, made similar claims on thin evidence. The hackers, they explained, “appeared to cease operations on Russian holidays, and their work hours seem to align with the UTC +3 time zone, which contains cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg.”

In a thorough and thought-provoking piece on Russian hacking, investigative journalist Yasha Levine picks this “evidence” apart:

So, FireEye knows that these two APTs [Advanced Persistent Threats] are run by the Russian government because a few language settings are in Russian and because of the telltale timestamps on the hackers’ activity? First off, what kind of hacker — especially a sophisticated Russian spy hacker — keeps to standard 9-to-5 working hours and observes official state holidays? Second, just what other locations are in Moscow’s time zone and full of Russians? Let’s see: Israel, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Moldova, Romania, Lithuania, Ukraine. If non-Russian-speaking countries are included (after all, language settings could easily be switched as a decoy tactic), that list grows longer still: Greece, Finland, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Yemen, Ethiopia, Kenya — the countries go on and on.

“This is forensic science in reverse,” Levine writes. “First you decide on the guilty party, then you find the evidence that confirms your belief.”

Does any of this mean that Russia is not actually hacking or attempting to hack American institutions and agencies? Of course not. All major powers dedicate huge amounts of time and resources to hacking each other, pretty much on a constant basis. It’s highly doubtful that hacking ceases on national holidays. The question is whether Russia is actually responsible in the instances described by firms like CrowdStrike and FireEye.

The Vault 7 leaks are not exactly a smoking gun for those who maintain Russia’s innocence where the DNC hacks and leaks are concerned — but they’re not insignificant either. If anything, the new leaks should make people think a little harder before putting their complete trust in the CIA’s public conclusions about the acts (or alleged acts) of enemy states.

On the other hand, for those who still believe Russia is responsible for the DNC hack, the latest WikiLeaks dump could also easily have confirmed their beliefs. Russia is the only country specifically named by WikiLeaks as a potential victim of these “misdirected attribution” tactics. This will heighten suspicions that U.S. intelligence agencies have in some way been infiltrated by Russia to facilitate the leaks of damaging (but true) information. It will confirm, for some observers, that WikiLeaks is in Vladimir Putin’s pocket.

Personally, given that WikiLeaks has an impeccable record in terms of the authenticity of the material it releases, I’m inclined to disagree with the analysis that paints Assange as a Kremlin stooge. What we really need to be skeptical about is the way these stories are framed and promoted by both government agencies and media. The fact that the CIA — an organization of professionals trained in the most sophisticated methods of deception — is front and center promoting the idea that Assange is a Russian agent, should be enough for anyone to take that idea with a pinch of salt.

The Russia story has turned into a game of "pick your favorite conspiracy theory" — but what we label as conspiracy theory is most often whatever we find unpalatable to our built-in biases. We go around looking to confirm our own theories by seizing on the evidence that matches our ideas of how things are. No one is immune to this.

What we should work toward is a better awareness of these tendencies. If journalists can do that — and they should — perhaps they can begin to employ more exacting standards to their investigations and reporting. Maybe then we can come a little closer to determining the real truth, rather than the truth as we would like it to be.

Shares