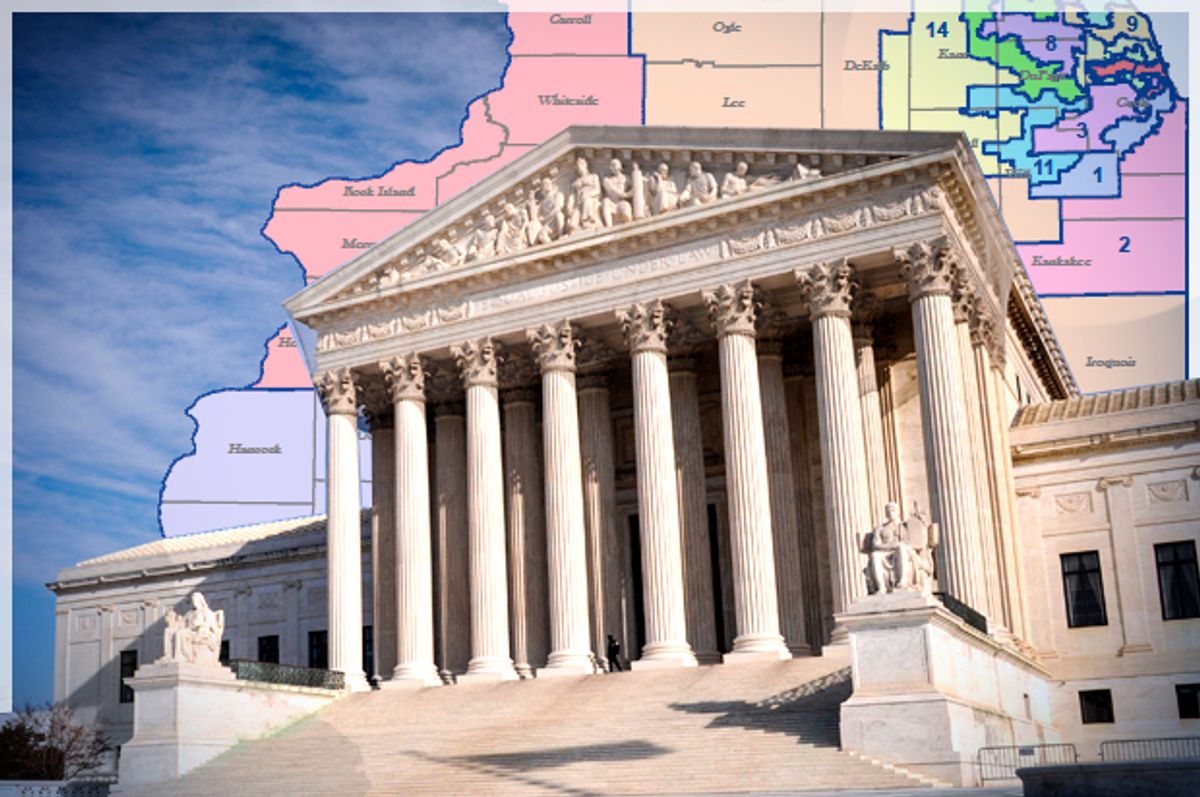

Gerrymandering, the process of drawing distorted legislative districts to undermine democracy, is as old as our republic itself. Just as ancient: the Supreme Court’s unwillingness to get involved and determine a standard for when a partisan gerrymander has gone too far.

That might be changing. During the 2000s, Justice Anthony Kennedy expressed openness to a judicial remedy, if an evenhanded measure could be devised to identify when aggressive redistricting was no longer just politics as usual.

When the pivotal swing justice looks for a standard, law professors and redistricting nerds get to work. There are now several cases related to the extreme maps drawn after the 2010 census – by Republicans in Wisconsin and North Carolina, and by Democrats in Maryland – on a collision course with the Supreme Court.

The case with the most promise to deliver a lasting judicial remedy is Whitford v. Gill, from Wisconsin, which advances a fascinating standard called the "efficiency gap." It is the brainchild of law professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos and political scientist Eric McGhee, but has an elegant simplicity that is easily understandable outside of academia. If gerrymandering is the dark art of wasting the other party’s votes – either by “packing” them into as few districts as possible, or “cracking” them into sizable minorities in many seats – the efficiency gap compares wasted votes that do not contribute to victory.

In November, a panel of federal judges smiled upon this standard and ruled that the state assembly districts drawn by a Republican legislature in the Whitford case represented an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. “Although Wisconsin’s natural political geography plays some role in the apportionment process, it simply does not explain adequately the sizable disparate” advantage held by Republicans under these new maps, wrote the court.

The judges ordered new state assembly maps in time for the 2018 election – a big deal, considering these district lines have helped give Republicans their largest legislative majorities in several decades, despite years in which Democratic candidates receive more votes. But just as important, it accepted the “efficiency gap” rationale and sent it toward Justice Kennedy. If Kennedy finds it workable, it would become much more difficult for politicians to choose their own voters and rig maps in their favor.

If this case makes history, it will be thanks to the commitment of lawyers and political scientists, but also to the Wisconsin citizens who launched it, starting with regular meetings at a Madison tea room. The plaintiff whose name could become synonymous with taming the gerrymander and restoring fairness and competitiveness to our elections is a retired law professor named Bill Whitford. We sat down at a redistricting conference at Duke University this month to discuss his case, the efficiency gap and all the luck it has required along the way.

Let me start with the obvious questions: How did you become interested in redistricting? And how did you become the plaintiff in what could be the most important Supreme Court decision on partisan gerrymandering ever?

I’ve been a political junkie from the word go. I grew up in Madison. My mother was very political. By the time I was 13 or 14, I was a big-D Democrat, working on campaigns. I was chairman of the Young Democrats as an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin. Then I went to law school straight out of college, mostly interested in constitutional law. Baker v. Carr was decided [in 1962] while I was in law school. I wrote my very first academic article, as a student, on Baker v. Carr.

That’s amazing: Baker v. Carr is the decision that allows the federal courts to get involved in redistricting matters. The hunt for redistricting’s holy grail – a standard to measure partisan gerrymandering, the goal of Whitford – begins there.

Yes, it argued even then about what the standard should be. I got a job as a law school professor teaching assigned contracts, and then went a different way in terms of my academic specialties. But I always remained a Democratic activist interested in politics and redistricting. That’s my birthright, I guess!

Your retirement comes 50 years after the Baker decision, and at a time when Wisconsin is the new ground zero of the gerrymandering fight. Republicans captured both chambers of the state legislature in 2010, Scott Walker became governor, and the maps they enacted in 2011 are some of the most tilted any state has seen in four decades. Democrats win more votes, but Republicans win an outrageous 2012 Assembly supermajority anyway. How did you join the fight?

There was a group that met and talked in the Watts Tea Room in Madison that grew out of the lack of success of the first legal challenge to these maps. [The court found an unconstitutional racial gerrymander in that case and forced several largely Latino districts in Milwaukee to be redrawn.] I wasn’t a part of the original group, but the guy who was as responsible as anybody for it was a Wisconsin legislator and redistricting guru named Fred Kessler. We’d been active in Young Democrats as undergraduates. He knew that I was retiring and asked me if I would like to join the group. That’s how I became involved in this case.

Let me get this straight: You’re saying that we’re this close to a national standard on partisan gerrymandering because a group of frustrated old friends and retirees had a regular meeting at a Madison tea room and put this whole thing together?

Well, some of the members of that group were lawyers in the earlier case. They were very aware of the kind of information [about the behind-the-scenes GOP redistricting chicanery] that was available in discovery. We knew we had a lot of smoking-gun evidence that would indicate partisan intent, and it turned out that we had even more than we thought. But by then we also had the results of the 2012 elections, where Democrats got a majority of the statewide vote but only 39 percent of the seats. By any measure for partisan effect, that was pretty good data. Then we began shopping for lawyers and we stumbled onto Nick Stephanopoulos and Ruth Greenwood.

That’s remarkable luck: Nick and Eric McGhee had been studying the Wisconsin redistricting. Using a new standard they developed called the efficiency gap to quantify the impact of a partisan gerrymander, they discovered that you had one of the most unrepresentative legislatures in any state over the last several decades. How did you stumble across this?

One of the roles I played in the group was to reach out to professors in academia, both to feel them out for ideas and to see if they thought we had a decent test case. We thought we had a very good fact situation for a test case, but there was also the issue of whether we should wait for the 2020 cycle before it wound up in court. Rick Pildes of NYU Law School was one of these people. I just called him up cold.

Turns out, Rick got the original Stephanopoulos and McGhee draft paper where they explained the efficiency gap. As part of the election-law community, he’d been asked to make comments. He alerted us to this and suggested Eric would make a good expert witness. I read the article and saw that he talked all about Wisconsin. That’s how we got into the efficiency gap. Then in my initial phone call with Nick, he mentioned that his girlfriend was the incoming voting rights director for the Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights. Ruth and Nick soon came to Madison and started meeting with the group.

How do you explain the efficiency gap to your friends and neighbors? It’s complicated and involves math. What’s the elevator pitch?

I simply start out talking about "packing and cracking." They're the essential tools of gerrymandering. I don't really stress the efficiency gap. If I had to explain the efficiency gap, I'd go to the concept of lots of wasted votes – but I would first start off with packing and cracking, then explain wasted votes in the context of packing and cracking.

And what do we mean by "wasted votes" in this context?

Wasted votes are all the votes for the losing candidate plus all the votes for the winning candidate above 50 percent plus one.

The art of gerrymandering is the art of wasting the other side’s votes as efficiently as you can.

Yes, and the efficiency gap measures the way that a party favored to win does so by wasting as few votes as possible – voters that can then be spread into other districts. The party that’s disfavored by the maps wins their seats by a substantial margin. Those voters are packed into that district. In a cracked district, there are a lot of wasted votes for the losing party – who might get 45 percent – but very few for the winning party. That’s how I explain it.

Did a bell go off in your head when you saw this paper? This is it! This is the standard that we're looking for?

It's a possible standard. To tell you the truth, in the meetings with Nick and Ruth in Milwaukee …

I mean, people were talking about it today as the long-sought holy grail.

Some people were attracted to the efficiency gap. Others said, "Well, just a minute now, we want a test case of partisan gerrymandering. We don't want this to be a case which gets Nick Stephanopoulos his Ph.D. thesis!” I've become a fan more and more as time has gone on. But you have to remember, we were kind of beggars. At the time, we were looking for some free lawyers who would take the case!

An awful lot of luck has to happen. Assuming we win this case, a lot of little lucky things had to happen in the interim, like the recall election that allowed the Democrats to take control of the State Senate, without which we wouldn’t have gotten a lot of the discovery – the hard drives, the emails – that was part of the smoking gun on partisan intent.

When the Republicans redistricted, they set it up in a way designed to produce confidentiality: They had the State Senate and Assembly hire a lawyer with state funds, then sent over the actual map drawers – many of whom were legislative staffers – made them employees of the law firm, and tried to protect all their work under lawyer-client privilege. The courts blew through that and required disclosure.

But when the Democrats got control of the State Senate, they were suddenly clients of the law firm, because they were using state funds. They asked the law firm for the records. The law firm complied – and we discovered there were things that had been turned over to the State Senate leadership that should have been in the disclosure to the lawyers in the previous case, but were not: hard drives that contained not only the emails, but all the memorandums, all the drafting documents, draft maps, everything. The court just flipped at that.

What would you call the most insidious effects of partisan gerrymandering?

Well, I'd say there are two consequences that are most insidious. There are the various consequences in terms of legislation. Certainly the substantial defunding of the University of Wisconsin system, the right-to-work legislation – those would be examples.

The other impact is the noticeable dampening of enthusiasm for campaigning for local elections. At a statewide level, when you try to recruit people to run for office or work for campaigns, they think the idea of putting Democrats into the majority is hopeless. It’s had a real chilling effect in that respect, and quite understandably so.

There was an amazing number out of Wisconsin in 2016: Out of 99 state Assembly districts, 47 lacked a major-party challenger. Everyone looked at the districts, measured the likelihood of winning, and passed on even making a race.

That’s a pretty big number. It’s the lack of competitive seats. The efficiency gap nicely sums it up – there are many more Democratic seats that are won with 75-percent-plus of the votes than Republican seats. There are very few swing districts. The Democrats’ votes are packed, cracked and wasted. Then there are a bunch of Republican seats [where] they win around 55 or 60 percent – they win many more seats, much more efficiently.

What is your hope? Ideally what is the best result, as you look at this?

I hope we win. I hope the courts begin to get into the area of setting some limits. All the data shows that gerrymandering is only getting worse, by both sides. It's a problem, and a national one, of single-party control.

Right now, Republicans are doing it more than Democrats. That’s because more states have single-party Republican control than [are controlled by] Democrats. But I’m not claiming Democrats are holier than thou. The courts can shake that up a bit, and they need to. But it’s only going to set some limits. It doesn’t mean it’s the end of partisan gerrymandering.

It’s very encouraging to see everything that’s going on around the country. This is a real problem for democracy and an increasing number of people seem to understand that. Ultimately, we have to get redistricting out of the hands of legislatures. There are problems with commissions and a lot of issues about how you structure them. They’ll need structure from the courts. But the first essential step is to take the power away from legislators.

Have you spent any time examining alternative election forms like ranked-choice voting or multi-member districts, both of which would be more effective in providing choice and options to voters than a commission?

I am hardly an expert but I am familiar, because I am a political junkie and my friends do this kind of stuff. My gut tells me that’s a harder sell – but it’s certainly possible that you could get ranked-choice voting in many states and municipalities. That seems to be a good system to me, but it could take a while.

You started in a tea room. Now you’re on the verge of the Supreme Court. Not a bad run – and you could go down in history as the plaintiff who changed everything.

If we win, my grandchildren will know me as the plaintiff in this case. They won’t know what I did as a law professor. I get a lot of congratulations, but I really feel like what I did was a relatively small amount. My role has been small compared to a lot of the others. My fear would be that we win, and then there’s a change on the Supreme Court a year or two later, and it all somehow ends up reversed.

It’s nice symmetry to have spent time studying Baker v. Carr, and then coming back around to this. It’s been fun and it’s been a good retirement activity. Saving democracy.

Shares