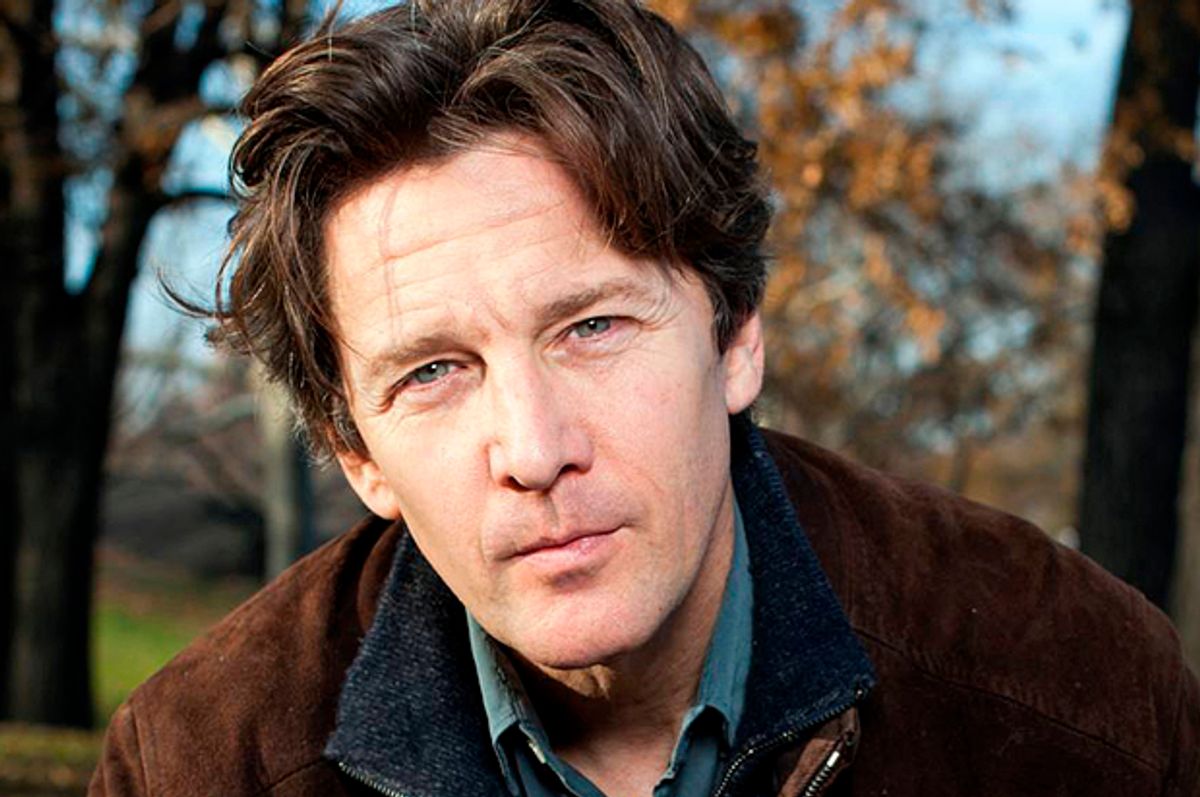

Escape, forgiveness and reconciling the past here in the present are themes Andrew McCarthy circles back to in both his award-winning travel journalism (six Lowell Thomas awards and counting) and in the acting roles that first brought him to renown in the 1980s and '90s. To huddle with Blaine from "Pretty in Pink," Dorothy Parker's first husband in "Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle" and the author of the 2012 memoir "The Longest Way Home," about a trip McCarthy made around the world before remarrying, is to stand between men who know their mistakes all too well and battle between facing them and running from them.

McCarthy's first young adult novel, "Just Fly Away," concerns 15-year-old Lucy Willows, who has just learned her father has a young son from a brief affair, and Lucy's escape from her feelings of betrayal and pain when the rest of her family doesn't react in the same way.

Salon spoke to McCarthy by phone about traveling without a plan, the wisdom of John Cleese and how his own kids' reading tastes lie elsewhere.

Between your last book [the 2012 travel memoir "The Longest Way Home"] and "Just Fly Away," you've spent a pretty considerable amount of time working in television in the director’s chair on shows like "Orange Is the New Black" and "The Blacklist." I was curious to know where you were creatively and emotionally when you decided that this was going to be the next thing you were going to do?

I started doing a version of this book probably eight or nine years ago, an adult novel about a guy who had a child out of wedlock from a one-night affair and how that secret affected his marriage. Then I struggled a few years and put it aside to write that other travel book that you’d mentioned, all the while directing, too.

Then at a certain point when I came back to the novel . . . I was actually sitting on a plane to go to Los Angeles and I thought of it suddenly from the girl’s point of view as "my dad’s an asshole, he's got this other kid across town." So suddenly I was writing what I knew instantly was sort of a YA book.

I found that very liberating. I was suddenly telling a story that I wanted to tell all the while without knowing this was the story I wanted to tell till I start telling it.

Was the decision to make this into a YA novel based on not only the age but point of view of the main character?

I don’t think it necessarily had to do with her age, because you can certainly write an “adult novel” from a 15-year-old's point of view.

But I knew instantly that I was writing a YA in the sense that it was speaking sort from that youthful urgency, that ferocious vulnerability that you have when you’re that age.

Lucy’s kind of alone in her anger at her father’s betrayal. She feels it much more intensely and personally than her sister or mother but has trouble explaining it to us as the reader.

I remember very much that adolescent feeling. Am I the only fucking person awake on the planet, and, simultaneously, is my life actually not going to happen for me? You know? That terror.

I think it’s a real revelatory moment in life when you realize our parents have their own lives and are not simply there to service our life. So it was an interesting thing to have her anger and then have her not be able to particularly articulate it in any way or understand it.

The novel leaves open the possibility that the other characters' seeming lack of fury at the betrayal could be a subjective reading too.

Yeah, actually Lucy is quite unreliable in that regard. And they are in different places of knowing it as well; like you said, her sister has known about it for a number of years, the mother has known about it, so Lucy is just in the immediate throes of finding out, so her response is much more charged than theirs. But Lucy is a fairly unreliable narrator, at best, that's for sure.

Mistakes and forgiveness are a theme you return to often. It’s definitely present in your memoir and even to rewind this back to the acting roles that made you famous in your 20s, those characters feel like they all have a larger backstory than they let on.

I think forgiveness is all we have in a certain way, right? I think, yes, we can forgive — what’s that Bob Dylan [line], you can come back, but you can’t come back all the way? It’s a little different after I’ve forgiven you or you’ve forgiven me, which is different and there’s a sadness to it, maybe a strength that wasn’t there before.

I do think that, too, everyone’s story is so much more. For years I was simply dismissed as a certain kind of actor because . . . when I was 22 "Pretty in Pink" took off in a way that no one could have suspected so all of us are instantly eager to just see a headline and categorize and move on. It’s like talking to someone and then suddenly they sit down and they start playing the piano. And I mean everybody is able to sit down and play their piano. That’s all anyone ever wants is to be seen.

What you’re describing sounds like a second cousin of this other theme I see in your work, this idea of escape, like the act of being seen and the art of escaping are somehow connected in an unholy marriage.

To be seen, but also I want to vanish. So they’re the opposite side of the same coin and I do have a strong yearning to escape, as it were, and understand the value in escape, and it’s not just running away but a running to.

I often don’t know what I’m looking for until I’m upon it and through it.

Two thirds of "Just Fly Away" is a process of and arrival at escape. Lucy fleeing to her grandfather in Maine seems like an attempt to understand why she seems to be the only one who feels what she does about her father's infidelity. That feels to me like one of those three or four Stations of the Cross of growing up, that we can’t distance ourselves from ourselves.

I remember looking in the mirror when I was 15, just wishing I could know what I would look like in 10 years — just because I know I’m going to get through whatever it is that I was going through — going, please, just let me see, just for a second, what I will look like when I’m 25. I needed to know that it’s going to change in a good way.

If we look at these three facets of your work, in acting, directing and writing, particularly with a focus on travel writing, those all require a different kind of being present for the work to succeed.

Acting is a very subjective thing, where you aim at a kind of emotional pool where you just sort of modulate yourself around and stay in as long as you need to stay in it, and then you leave. Whereas directing is much more [about being] the grown-up in the room, where you’re responsible for the room and you’re responsible for telling the whole story and responsible for creating an environment for those people who are in the subjective mode on their little surfboards to feel safe to do that. Writing is the same.

I heard John Cleese once talk about the open mode and the closed mode. When you’re acting you’re constantly in an open mode. You’ve got to be accessible and have things flow through you. Then in directing, you’ve got to be able to plug into that open mode between action and cut. Then cut, closed mode, grown-up. OK, technically, what do we have to fix? We need to fix that light over there so that the actors can walk over there. Now let me go back over here into this open mode. The writer comes up to you and says, "I think they ought to do it this way." You need to handle that input and then take it and communicate it to the actor in a way that he can handle it. So you’re constantly going to be switching between open and closed.

Is travel writing a hybrid of open and closed, because the experience in the place is new and presumably you’ve never been there before, so that’s a way you have to stay open, but there is also the knowledge that you can’t bring all of it back with you, that you have to edit and select and refashion it once you return home?

It’s like directing. You do all your homework, and then when circumstances present themselves, you’re relaxed enough to recognize what the story really is.

Like with "Just Fly Away," after seven years, it’s like, this is the story, idiot, it’s over here, it’s about the girl. It’s not about the guy.

You have to be open to the serendipity but also have a plan. I would say 40 percent of most of my travel stories are what I planned, and then 60 percent are things that happened along the way.

If I was all impulse then you just have meandering, episodic kind of things that have no structure and no drive. If it were all just story planning, then there is no room to breathe, and no surprise, and travel is nothing if not surprise if you’re traveling well. I learned an awful lot about directing by travel writing, for sure. I’m a much better travel writer because I started as an actor.

Tell me about these three different Andrew McCarthys.

The travel writer is the most joyful, the director is the most responsible and articulated grown-up, and the actor is the most insecure.

You’ve got three kids. Do they have YA reading habits that played any part in the construction of this book?

No, my son is not a reader. He said to me the other day, “Dad, I’m going to wait for the audio.” My daughter's into graphic novels. And my youngest guy, we read "Goodnight Moon" together last night. That’s where they’re at, reading-wise.

What else is cooking creatively for you in the near future?

I’m going to be directing on this new show called "Condor," which is sort of a television version of "Three Days of the Condor." I’ll be doing that for several months, then directing more "Orange Is the New Black," after that.

People for years have been saying, “Why do you never write? I mean, you write, so why do you never write anything like a screenplay or a television thing?” And I’ve always kept them very actively separate. I’m just finishing now my first screenplay, which is, again, on the same theme of those same two features of escape. Like most things that I finally act on, I’ve let it swim around for a while, and then I go, "If that’s not leaving me alone that’s the way I’m going to write that."

Shares