“Feminism, which has waged a crusade for rape to be taken more seriously, has put young women in danger by hiding the truth of sex from them.” — Camille Paglia, 1991

“Feminism is broken if anyone thinks the sexual hysteria overtaking American campuses is a sign of gender progress.” — Laura Kipnis, 2017

In a time when, thanks to the elected president’s own remarks about women, “pussy grabs back” is already a shopworn international slogan, it may seem a bit, well, inopportune to propose that rape culture is a fallacy, or that intensifying measures to address it are at best ineffective and at worst feed the fire they were meant to extinguish.

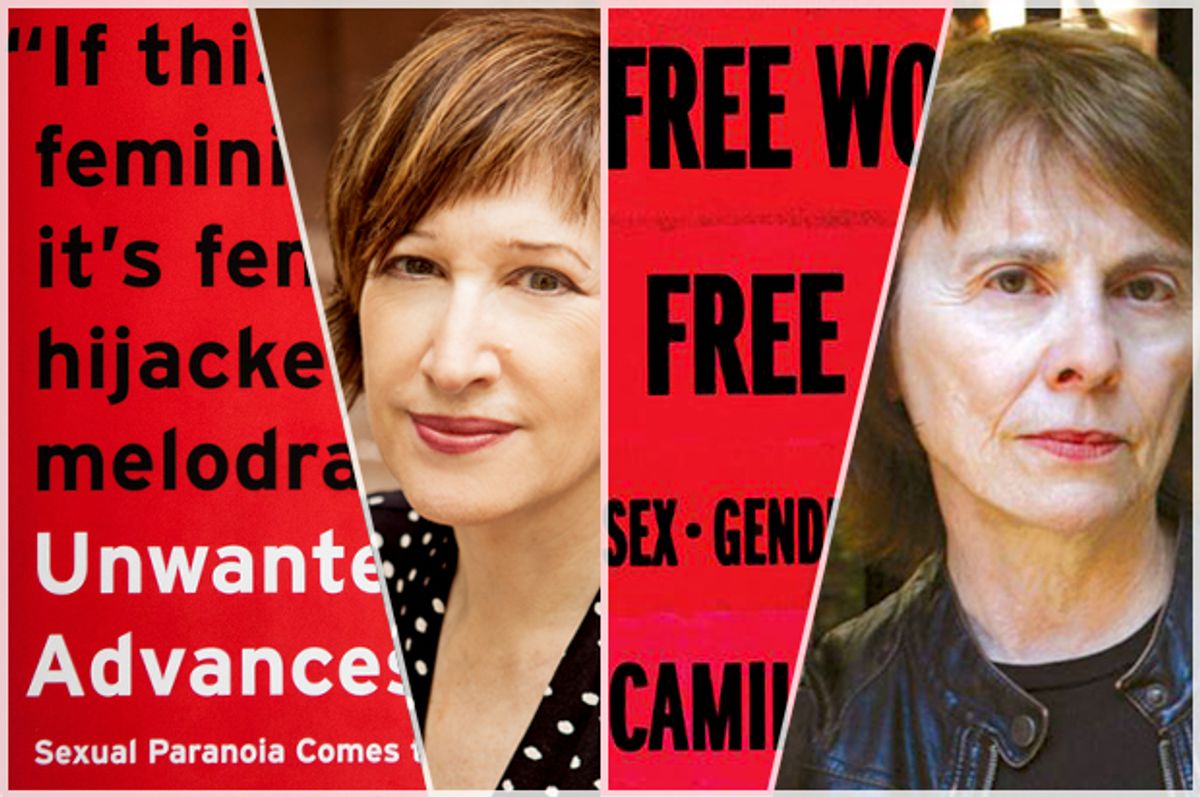

That’s exactly what feminist, film professor and culture critic Laura Kipnis argues in her seventh book, “Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus,” released April 4. Responding to the rising zealotry of “feminist paternalism,” as instituted through the expanded purview of Title IX (a policy initially meant to equalize federal funding granted to men's and women’s sports, but that now includes any type of sex-based discrimination), Kipnis chronicles not only the inconsistencies in its ongoing national application, but her own 2015 investigation at Northwestern after she wrote an essay about Title IX for the Chronicle of Higher Education.

That’s right: Kipnis was investigated by Title IX for publishing an essay on Title IX — an essay alleged to have itself created a “chilling environment” on campus for sexual assault survivors. “The latest demands for intellectual conformity may come in progressive packaging,” Kipnis writes, "but feminists and leftist should be flinging these pieties away like lumps of dung, not kowtowing to the virtue parade.”

Left-wing feminist scholar turned reluctant free-speech Joan of Arc? Unsurprisingly, conservative pundits couldn’t wait to claim her as patron saint. Kipnis jests in her intro that “when someone likes me gets lauded on the right, politics as we know it is officially incomprehensible,” and it’s hard to disagree. Might intellectual freedom be the one spot these days where members of the far left and far right tend to concur? No matter one’s leanings, it seems fair to say that Title IX — however well intentioned — is a federal measure pocked with holes, its process defined unevenly over the past five years according to each university’s subjective, sometimes idiosyncratic, interpretation of what constitutes actionable harm.

Reviews of “Unwanted Advances” have been mostly positive, if openly conflicted — two published by the Times in less than a week, both authored by women, the second by Jill Filipovic, a “feminist writer and (nonpracticing) lawyer relatively well-versed in the details of Title IX and campus sexual assault.” Among other gripes, Filipovic takes issue with what she perceives as Kipnis’ characterization of complainants as scheming schoolgirls, yet admits that “she couldn’t help reading . . . with pen in hand, furiously scribbling in the margins.”

As a feminist writer myself — and teacher of university students for the past 14 years — I finished the book with shaking hands, as though I’d traveled a ring of Dante’s inferno but the hell was my own professional home. Was the same paranoia going down on my campus? Was it curbing sexual assault? Or was it, more immediately, threatening priceless freedoms?

Hanna Rosin has called Kipnis’ take “a revelation” that “makes you fear for a whole new set of reasons,” and she’s right. But it is less a revelation of argument than of rhetorical genius and academic valor. Kipnis is not the only one to confront the abuse of Title IX, take issue with “affirmative consent” laws, or decry certain social tenets that have been dubbed “rape culture” as inherently problematic. Though her account of both her own and others’ Title IX travesties makes for a gripping, often terrifying, read, many of her central ideas mirror those I read in high school, stumbling upon an anthologized (and surely unassigned) reprint of “Rape and Modern Sex War” by none other than grande dame provocateur Camille Paglia.

“College administrations are not a branch of the judiciary,” Paglia declared at end of the 1991 essay. “They are not equipped or trained for legal inquiry . . . they must stand back and get out of the sex game.” This, 20 years before the Obama administration made the historic move to expand Title IX into matters of sexual imperilment, and more than 25 years prior to Kipnis’ exposé.

Throughout the late ’90s, Paglia's writings compelled me not only to reassess my nascent (virginal) assumptions about sexual politics, but fanned my desire to someday put words to paper that others might find edgy or even dangerous. “We need a new kind of feminism,” Paglia wrote in her 1993 treatise “Sex, Art, and American Culture.” “One that stresses personal responsibility and is open to art and sex in all their dark, unconsoling mysteries. The feminist of the fin de siècle will be bawdy, streetwise, and on-the-spot confrontational, in the prankish Sixties way.”

Inability to define "fin de siècle" aside, I thought myself prankish, a little bit bawdy, and my style swerved a bit flower-child-punk. I was scrappy — or at least I thought I was. Paglia felt gutsy and powerful — the antidote to “Reviving Ophelia” panic that felt utterly trivial to my own experience. If my adolescent self didn’t need saving, why on earth would my woman self need it?

Kipnis reasserts, now, that it shouldn’t. “What I’m saying,” she stresses, “is that policies and codes that bolster traditional femininity — which has always favored stories about female endangerment over stories about female agency—are the last thing in the world that’s going to reduce sexual assault.”

As for the things that might, Kipnis suggests swapping a “rhetoric of emergency” for an embrace of female agency, in part by dropping the “self-induced helplessness” that binge-drinking all but guarantees. “I fully believe that women should be able to pass out wherever they want — naked, even — and be inviolable,” she professes (a bit glibly). “One hopes such social conditions someday arrive. The issue is that acting as if things were different from how they are isn’t, thus far, working out.”

Not because most college women are being raped or assaulted, she argues, but because most college women aren’t having very good sex, for reasons thornier than a squeamish blow job or barely sentient hookup. “It’s not just about taking back the night,” Kipnis writes, referring to the famous anti-rape movement, “it’s about admitting that progress is uneven and ambivalent on both sides of the gender divide, especially if what looks like female independence and convention-flouting ends up restoring feminine conventionality through the back door.”

Self-ordained a “libertarian feminist,” though she herself has supported Democratic candidates in all but the most recent presidential race (she voted for Stein), Paglia’s support of such “independence” is on full view in her latest, and seventh, tome, “Free Women, Free Men: Essays Sex, Gender, Feminism,” which came out only weeks before “Unwanted Advances.” From the looks of the books’ eerily similar packaging, one might think their publishers set up a two-for-one deal with an indolent designer. Both covers are an Everlast red, their titles a stern sans-serif black. When stood side by side, the hardbacks resemble an intellectual boxing match: “Paglia’s heavyweight Tyson vs. Kipnis’ nimbler Mayweather.”

What the contrarians share is the assumption that women are free, adult agents — free to decide, to desire, fuck up, and fuck over. But for as much as the two might initially seem interchangeable, in a few far-reaching ways they couldn’t be more different. “No one’s saying women get assaulted because they pass out in dicey locales,” Kipnis writes. Actually, Paglia (kinda) has, and is unlikely to pull a volte-face. From 1991: “A girl who lets herself get dead drunk at a fraternity party is a fool. A girl who goes upstairs alone with a brother at a fraternity party is an idiot.” From 2017: “I still stand by every word of my date-rape manifesto. Women infantilize themselves when they cede responsibility for sexual encounters to men.”

Chief among their differences is the embrace or rejection of biological essentialism. In her review for Salon of Kipnis’ 2006 book “The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability,” Laura Miller put it well: “[A]lthough Kipnis is willing to admit that some parts of the female psyche have proven ferociously resistant to change, she doesn’t think that the situation is intractable . . . she doesn’t believe that the deep layers of the ‘symbolic imagination’ are hard-wired.” Indeed, much of “Unwanted Advances” devotes itself to redressing the trope of men-as-predators as exactly that: a trope, not a biological given. “Under rape culture,” Kipnis claims, “. . . [m]en need to be policed, women need to be protected. But this is paternalism, not feminism.”

On the flipside, when Paglia isn’t waxing nostalgic for the freewheeling ’60s, she’s lauding the paternalism of distant yore — the “old days . . . where fathers and brother protected women,” and “men knew that if they devirginized a woman they could end up dead within twenty-four hours.” (Yikes, and also . . . really?) To Paglia, any sense of liberated femalehood is illusory if unaccompanied by utmost respect for the libidinal, ergo creative, urges of men. “There are some things we cannot change,” she writes in 1992's "Sex, Art and American Culture." “There are sexual differences that are based in biology. Academic feminism is lost in the fog of social constructivism. It believes we are totally the product of our environment. This idea was represented by Rousseau. He was wrong.”

He was wrong. Something about Paglia’s shot-blast of simple declaratives seduces in its own right — as much in 2017 as it did when I read these words two decades ago. But I’m not 16 anymore, and Paglia’s one-two punch feels all too easy now. Respecting male libidinous urges feels rather silly to me, especially given that so much of our culture spends so much time doing that work already. And calling any victim of sexual assault an “idiot” (male or female; let’s not forget that men can be raped, and that’s not including prison rapes, which are woefully under-examined) feels downright regressive, not to mention cruel. And for all its bravado, “Free Women, Free Men” sometimes feels like replaying an old CD on which about half the tracks sound scratched. Paglia hasn’t changed with the times, and neither have her arguments. Black-and-white logic reigns, and she rarely, if ever, plumbs the gray.

In the more than two decades since I came upon “Rape and Modern Sex War,” gray has comprised a good deal of my own sexual dalliances, disappointments and misadventures. Like most women, I have been discriminated against based on my gender, and have endured some compromising situations that no amount of prankishness or scrappitude could have possibly avoided. But I have also in my time made some unwanted advances of my own — toward more than a few men, and at least one woman (none of them students, to be sure).

I don’t agree with Paglia when she says that she, unlike men, could never enjoy the “moon and sand, the ancient silence and eerie echoes” of the Great Pyramid in Egypt. “I am woman. I am not stupid enough to believe I could ever be safe there,” she says. Speaking only for myself, I’ve traveled across the world twice alone and credit these sojourns for not only the richest experiences of my life, but also a basic faith in the human condition. Did I ever run into sexual danger? Of course I did. But it hardly seemed that men were, as Paglia often seems to suggest, stalking the globe like rabid wolves. Reality was a lot more complicated, and a hell of a lot more human.

It is precisely the gray where Kipnis summons her strongest stroke, swimming the murkiest depths of our sexual psyches. “Putting male sexuality on trial isn’t a bad thing,” she writes, “but we don’t want to turn ourselves into sexual hypocrites along the way by leaving ourselves out of the story, do we?” This woman, at least, does not — and “pussy grabs back” feels part of it. Even if the current is choppy and the shore miles off, the journey seems more important than ever, and one feels grateful to tread behind her.

Shares