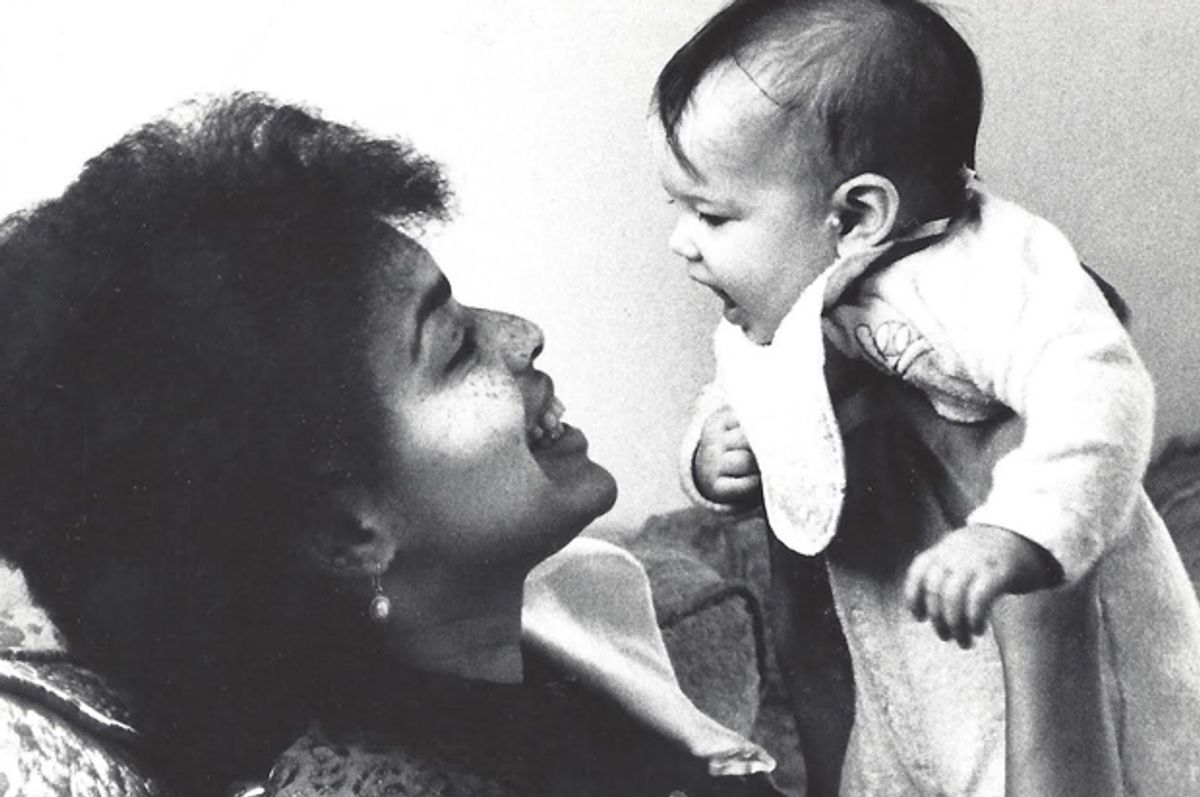

On a hot, humid New York City morning in 1980, I stood with my mother in the checkout line of an A&P supermarket near our home. As she pushed our groceries along the cashier’s belt with me trailing behind, mom realized she had forgotten her wallet at home, but she had her checkbook. Leaving me standing alone in the line for a moment while she saw the manager to have her check approved, the clerk refused to bag our groceries and hand them to me. She was black, and I was white. “These groceries belong to that woman over there,” the woman nodded towards my mother. “They ain’t yours.” Confused, I said, “But that’s my mother. I'll take them for her.” She looked me up and down. “No,” she said, her voice cold.

The clerk refused to believe that indeed I belonged to, and came from, my black mother, until mom returned to find me choking back tears. She gave the clerk a tongue lashing, which was not her style, and we left the market. Later, mixed Native American and black children threw stones at me near my home on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation as I rode my bike. They yelled, "Get off our land, white girl!" These painful and strange experiences gave me my first taste of racial prejudice, and they have stayed with me all these years.

I am a child of many nations. I am white, I am black, I am Native American. I am West Indian, German, Irish. Brown and light together — integrated, not inter-racial, because race means nothing when you come from everywhere.

This Sunday's New York Times Race-Related section ran a fascinating piece on DNA and racial identity by West Chester University professor Anita Foeman. For the past decade, she has asked hundreds of people to take part in ancestry DNA tests, and to date, over 2,000 have participated. "But first," she wrote, "I ask people how they identify themselves racially. It has been very interesting to explore their feelings about the differences between how they define themselves and what their DNA makeup shows when the test results come in."

Those results are often startling to the subjects and rife with racial stereotypes, Foeman found. According to her studies, some who came up with surprise Asian heritage in spite of looking white or brown noted, "That’s why my son is good at math!" Others who explored African heritage responded, "I thought my biological father might be black; I heard he liked basketball." Many of us harbor deeply-rooted prejudices that we aren't even aware of, until it matters to us.

I don’t remember what mom said that day in the supermarket, but I can tell you that while she had been the object of many, many racist remarks and challenging situations in her life, she was not entirely prepared for what happened that day. That's not to say she didn't talk about the reality of how our family was different from others. To try to address the dearth of literary references to kids who looked like me, my mother physically altered my childhood books, using markers to make one parent brown and other other white, while the child originally drawn remained white-appearing, like me. But the scene in the supermarket still took her by surprise.

Confrontations over race can still catch Americans unprepared, such as when Rachel Dolezal, the now-former head of the Spokane, Washington chapter of the NAACP, appeared on the media radar. Dolezal, who stopped by Salon recently to talk with me on her book tour, was born white but identifies as black and calls herself “transracial.”

[jwplayer file="http://media.salon.com/2017/03/3.28.17-Alli-RachelDolezal-Trans-v3.mp4" image="http://media.salon.com/2017/03/VIDEO_PHOTO-caitlyn.jpg"][/jwplayer]

Dolezal was “outed” two years ago by her biological parents for not being black as she had claimed, and subsequently resigned from the NAACP. She became a polarizing figure under heavy media scrutiny as she appeared to dodge questions about her unconventional chosen identity. She has been unable to continue to work as a university instructor of African and African American art history, and to this day is despised by many observers, black and white, for posing as a black person.

My Salon colleague D. Watkins, an African American writer from Baltimore, wondered why Dolezal couldn’t just “use her whiteness to advocate for black people,” rather than making up and living in her own fantasy world where race and ethnicity no longer cause any social or political delineations. He is one of many to hold this opinion, and it's one I agree with.

Rebecca Carroll wrote for Dame in 2015 about what she calls Dolezal's "apocalyptic, White privilege on steroids" with a palpable anger shared by many people of color. When I talked to my childhood writing mentor Barbara Campbell, a former New York Times reporter who is African American and has two multiracial sons, she wondered about Dolezal with a mix of anger and genuine confusion. “What is wrong with that woman? I feel empathy for her, because she is clearly delusional, but she can step out into the world as a white woman any time she wants to stop being 'black.' Black women don’t have that luxury.”

Campbell explained that growing up in St. Louis, she had many light-skinned relatives who resembled Dolezal and could "pass" for white, but otherwise lived their lives as people of color. “They would go to 'work white,' because they could earn more money and get better-paying jobs, but then they would go home and be black.”

Why, wondered many, would someone white want to live within the very real challenges of being black in America, when she had a choice? Dolezal's explanation? She doesn't define herself by race, just a feeling of affinity with the black culture she's always had.

As one might expect, the last few years have been tough since her exposure, she told me, noting her newly adopted legal name, Nkechi Amare Diallo, which she claimed was a “gift” to her by a Nigerian man. When she arrived at our offices, it was hard to know what to think, or believe. Frankly, it was hard to feel any animosity at all, despite the vitriolic sentiments many of my dark and light-skinned family, friends and colleagues had for Dolezal. She arrived carrying her beautiful, light brown baby son, Langston Hughes (Yes. Stop. That’s his name. What can you do?), who was cared for by her adopted black sister, Esther. Dolezal appeared like any other tired, working mom. I offered her coffee, and empathy, rather than taking an adversarial approach.

I did suggest, however, that some of the passages in her new book, “In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black and White World," were outrageous and possibly specious. Dolezal shrugged. “I don’t expect everyone to agree with or believe me,” she said. Among her claims: she grew up living in a tee pee in Montana (my Native American percentage shudders). She was beaten by her parents and forced to weave and wear a coat loomed from dog hair. She identified with people of color from an early age, after reading her grandmother’s National Geographic magazines, and spread mud on her face to try to feel what it was like to have brown skin. Dolezal has said some very polemical things, some — dare I say — dumb things, that do not make her a sympathetic figure. Comparing her white Montana childhood to what chattel slaves experienced, even if indeed she was miserable, is a stretch by any measure, and engendered rightful animus from real black folks.

Juggling Langston with one hand as he fussed after our interview, she inscribed a copy of her book to me with a careful and thoughtful note. Esther, sitting nearby, kept a watchful eye on the baby, and me. She was adopted by Ruthanne and Larry Dolezal in May 1995 at three months old (according to an interview their father Larry Dolezal gave People Magazine in 2015), and has sided with Rachel consistently, in the face of dissension between the other adopted siblings. They — and Dolezal's parents — say both Esther and Rachel are guilty of flights of invention, and in 2015, Ruthanne Dolezal told People, “Esther suffers from reactive attachment disorder and she seeks to cause trouble in the family. She is a chronic liar.”

In a 2014 blog post, Esther wrote: “I grew up in a pretty messed up family. And by messed up, I don’t necessarily mean dysfunctional (we were that too), but just plain strange.”

Whatever the reality, some mad funky stuff must have been going on in the Dolezal family to cause Rachel to want to be someone else. Any person in an abusive situation can relate to the desire to be somewhere, or someone else, so much so that the brain does funny things to make it so in one's own mind. Or maybe she made it up. We'll never really know, as it's her word against her parents'. But that isn't the point, really.

The majority of the world may see Rachel Dolezal as a perma-tanned, African-braided town crazy, tone-deaf around the realities of white privilege and the acknowledgement of others' lack thereof. Some may feel sorry for her. And yet she says she has many quiet supporters, people who themselves feel different and unaccepted in their ethnicity because they look a certain way.

Sitting here in my white skin, with my half-brown black and Native American family, I felt a sadness for Dolezal. I waited for anger. But I found I couldn't — didn't want to — hate her, because though I'm a bonafide part-person of color — what I fondly refer to as a "stealth sister" — I am also a sort-of Zelig myself. I think anyone who wants to work for positive change deserves a chance to try. But the first of many differences between Rachel and me is that instead of trying to be different, I learned to be myself and to stand up for others, no matter their skin tone — but especially if they were brown. Because I watched racism happen to my beloved, smart, eloquent, beautiful, capable, passionate, kind, PhD-bearing brown-skinned mother, and so I know what it means to have limited choices, even as I have been blessed with many. And because I know that while Dolezal could choose at any moment to resume — not "pass" for — being white at her convenience, this is a privilege no person of color will ever enjoy.

Steven W Thrasher, a journalist who is half white and half black, wrote in the Guardian in June 2015 about the Dolezal phenomenon, when the story broke. "Many are, and may remain, put off by the sight of a seemingly fair-skinned white woman who passed herself off as a light-skinned African American woman and became a local leader in one of the nation’s most venerable black civil rights group," he noted. "But like it or not, she’s exposed how shaky and ridiculous the whole centuries-old construct of individual “race” is."

Even UNESCO, The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, issued its "Statement on Race" in 1950. In it, the social scientists declared that there was no scientific basis or justification for racial bias, according to a piece published July 18, 1950 in The New York Times. It asserted that humans were equal based on four premises, as summarized by encyclopedia.com: "(1) the mental capacities of all races are similar, (2) no evidence exists for biological deterioration as a result of hybridization, (3) there is no correlation between national or religious groups and any particular race, and (4) “race was less a biological fact than a social myth”. Ultimately, it said, biology was the “universal brotherhood of man.” The controversy around the UNESCO statement and some of these ideas clearly remains to this day.

And race and color, or ideas about where we come from and what that means, are fraught with challenges. Sometimes we discover, upon reflection, that we don't look like what's in our past, or how we feel about this make-up. Professor Foeman, having researched her own DNA and that of thousands of others who didn't "look" like everything in their makeup, notes a change in thinking. "Today I look at faces, even my own, with new recognition," she wrote. "I see that people regularly share narratives that miss something their physical features suggest, and sometimes we find ancestry that we would not have imagined. It is a new twist on an old narrative made possible by cutting-edge science."

Checking the "other" box on my college applications years ago was a metaphor for fitting in everywhere and nowhere, always realizing the "gift" of light skin, trying never to take it for granted, and also remembering how kids threw stones at me for being white in the wrong place. Will kids throw stones a generation later at my own children? Maybe so. And what you see on paper is often not what you get, professor Foeman's study highlights: When I arrived as a freshman at Vassar College, having checked said "other" box, I was assigned a "big sister" by the African American Association of students. The young woman tried to appear nonchalant when I met with her, but of course I was not what she expected. Nevertheless, she was kind and welcoming, but we both ultimately determined that the African American Club was not a natural home for me. I was too different, and I didn't fit in. But what matters is that they would have had me.

When someone tells a racist joke, I flinch on so many counts, for all my people. I, like Rachel (and, it's worth noting, many sociologists), support the notion of race as a social construct, as did my mother. I also hope that collectively we can move forward with a humanity that embraces identity choices without brazenly appropriating the harrowing experiences of others, like slavery. But I do not forget that we aren't there yet. And I do not create fables around difference, and dissonance. No one should.

From her death bed, my mother and I discussed many things, and one of them was that she insisted I be an agent for change. She also reaffirmed that no matter what people thought of my heritage, it was most important to be a humanist — that is, to consider and respect all parts of my heritage, especially because I look white.

I don't care that Dolezal lied, personally. I'm just not that invested in anything about her. I don't feel betrayed. But I do understand the ire she engenders, and why many feel how they do about her. Some will argue that writing this article feeds her delusions and gives them more of a platform. Maybe, but it also affirms Dolezal's — and my own — thinking that a greater, ongoing discourse is important around identity and color discrimination. Not just her identity — everyone's. “I’m trying to move forward," said Dolezal. "And, I really hope that . . . if people don’t agree with my identity, we can agree to disagree; we can rally around our shared ideals of justice and equality and freedom and work together.” I agree with that. Do you?

We’ve closed comments on this post. If you’d like to respond to the story or share your own, send a note to lifeletters@salon.com, and we may publish it in a future follow-up post.

Shares