Thanks to the new movie starring Gal Gadot, Wonder Woman is in the pop-culture spotlight as never before. She’s never been hard to find in the comics, having been continually published since 1941. But if you open up a Wonder Woman comic, you’ll notice the words “created by William Marston Moulton.” That’s not quite the whole story.

Some of that story is explored in Jill Lepore’s 2014 book “The Secret Origins of Wonder Woman.” Lepore makes a valid point about the complexities of Wonder Woman’s authorship: “Her origins lie in William Moulton Marston’s past, and in the lives of the women he loved; they created Wonder Woman too.” Lepore supports this idea well in an indispensable piece of comic-book scholarship.

But there’s another Wonder Woman creator who is often ignored because of an ironic blind spot in the visual medium: Harry G. Peter. The artist who drew Wonder Woman since her very beginnings rarely gets credit for his crucial contributions to this character.

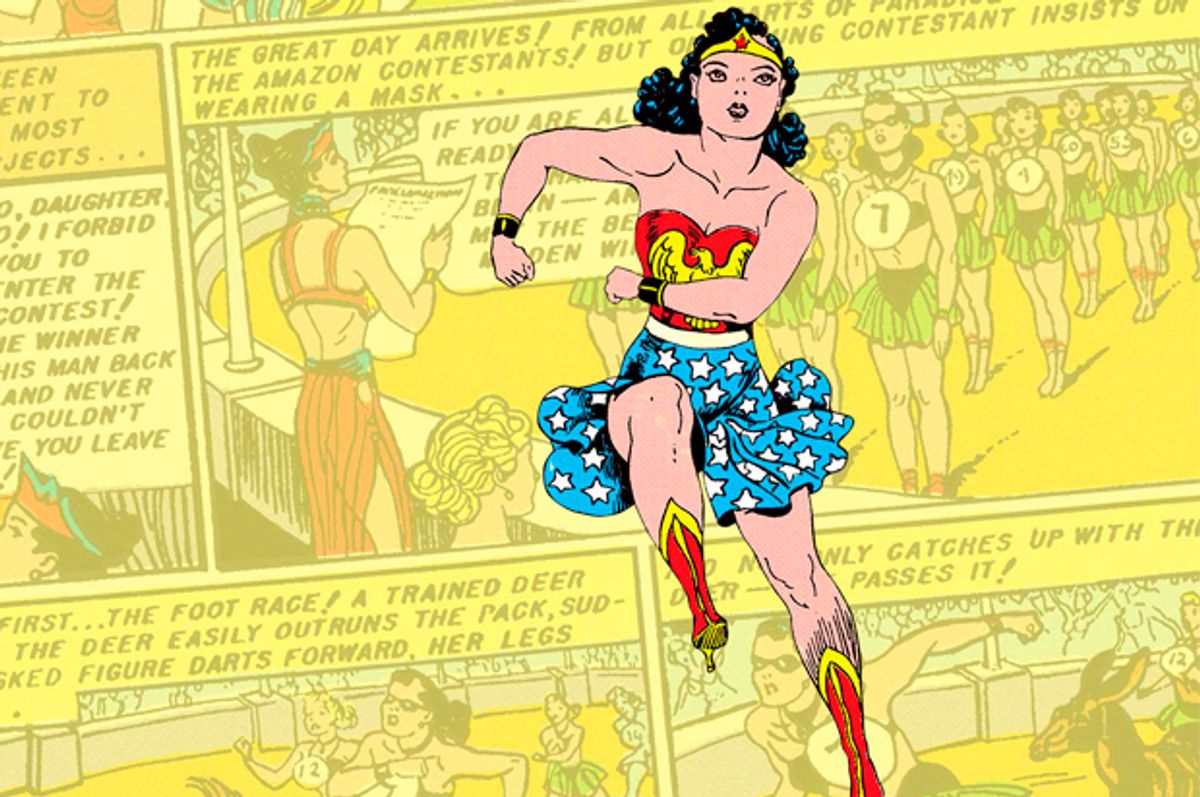

Peter illustrated the very first appearance of Wonder Woman (back in "All-Star Comics" No. 8 in 1941) and defined her look for years. With Wonder Woman back in the pop-culture spotlight, it’s worth remembering the artist who brought her to life so vividly.

One reason Marston gets all the credit for creating Wonder Woman is that he was an eclectic, brilliant guy who said things like, “Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world.” Marston — a feminist, psychologist, lawyer and filmmaker — didn’t just create a superhero with a lasso that makes people tell the truth, he contributed to the creation of the real-life, lie-detecting polygraph. His personal life should be the subject of an ongoing comic and/or HBO series as well. Marston had a polyamorous lifestyle for decades, living with (essentially if not legally) two wives: Sadie Holloway and Olive Byrne. You can see why Wonder Woman fans and critics would focus on him.

Harry G. Peter (often called H.G. Peter) didn’t have the same exciting biography as Marston, but he did have some feminist credentials as a contributor to "The Modern Woman," a section of Judge magazine dedicated to pro-suffrage editorials. Peter, a veteran illustrator who was 61 when he co-created Wonder Woman, also drew the Wonder Woman newspaper strip that began in 1944, and he drew every single Wonder Woman cover from 1941 to 1949.

Those covers have a timeless power. 1943’s "Wonder Woman" No. 7 featured the intoxicating idea of “Wonder Woman for President,” as men and women cheer on the podium-banging heroine. On the cover of "Wonder Woman" No. 6, an attack by villainous Cheetah couldn’t be more kinetic and visceral, as she swoops down to attack, with Wonder Woman’s hair in one hand and a huge knife in the other. On 1944’s "Sensation Comics" No. 26, Wonder Woman stops a train while showing off a muscly, heroic pose that would make Superman jealous. At a time when women's rights feel under threat, these visuals feel more iconic and inspiring than ever.

Lepore’s descriptions both minimize and reveal Peter’s hand in Wonder Woman’s origin. She describes the insanely high expectations for the character: “Peter got his instructions: draw a woman who’s as powerful as Superman, as sexy as Miss Fury, as scantily clad as Sheena the jungle queen, and as patriotic as Captain America.” Peter nailed this difficult assignment, as Lepore describes: “In 1941, Peter made some sketches and sent them to Marston; Marston liked everything but the shoes.” In other words, Wonder Woman’s enduring look was almost entirely the creation of Peter.

Sadly, artists getting insufficient credit is an old, undying problem in comics. Artist Declan Shalvey — best known for his work on “Moon Knight” and “Injection” with writer Warren Ellis — has become a proponent of what he calls “#artcred.” Shalvey laments an all-too-typical situation: “When people talk about comics, they often attribute the work solely to the writer of the project, and artists are rarely credited as co-authors of the work. The comic book medium has a substantial issue with artists getting the credit they deserve.”

Harry G. Peter deserves credit for a monumental accomplishment that shouldn’t be treated as the work of a hired hand. He didn’t just carry out orders from above to invent a revolutionary, feminist superheroine who possessed power, sexiness and patriotism: He created that unlikely visual combination, stocking a goldmine DC still benefits from today. Through co-authorship, volume of output and quality of work, Peter defined an immortal character, and he deserves credit. As Shalvey aptly puts it, “Drawing is creating too.”

Shares