For the entire eight years of the Obama administration, the congressional Republicans turned the national debt into their cudgel of choice against the Democrats and the White House. Prior to that, no one on the GOP side ever really talked about the debt -- or the budget deficit, for that matter -- mainly because for the first six years of the George W. Bush administration their party controlled both chambers of Congress as well as the presidency.

Once Obama took the reins in 2009, suddenly the national debt was a thing again. In fact, the Republicans proceeded to lie to their voters with the utmost cynicism, conflating the status of the debt with the status of the budget deficit, and in some cases deliberately mixing up the two numbers. Under Obama, the budget deficit was reduced by more than a trillion dollars, but since the national debt grew, the Republicans told their people that Obama had “doubled” the deficit.

During his 2012 campaign, Mitt Romney repeated: "The president said he’d cut the deficit in half. Unfortunately, he doubled it." Well, no. By the beginning of Obama’s second term, the budget deficit was absolutely cut in half from its high point of $1.4 trillion in 2009 to $680 billion in 2013. To be perfectly clear about this: The deficit is not the same as the national debt, but Romney and his party wanted their people to believe it was. Otherwise it would have meant giving the Democrats credit for presiding over a major fiscal savings. Indeed, by the end of 2015, the deficit had dropped to $438 billion, around a trillion dollars lower than George W. Bush’s final budget deficit. (The 2009 budget was Bush’s last, approved by the former president in October 2008.)

Nevertheless, it was this confusion that helped the Republicans get away with playing brinksmanship with the debt ceiling on several harrowing occasions. Making matters worse, the Republicans allowed their supporters to inaccurately believe that the debt ceiling had to do with curbing new debt when, in fact, it was about paying existing Treasury bond holders and other creditors. Reneging on the debt ceiling would’ve meant defaulting on our debt payments, not just to nations like China, but also to innumerable American citizens who own T-bills as a safe, conservative investment vehicle.

All in all, a default would have meant destroying our national credit rating and quite possibly sparking a massive worldwide recession. Incidentally, this misunderstanding about the debt ceiling is what made President Trump’s remark about repaying the debt for pennies on the dollar so ludicrous.

So that brings us to 2017, when there’s one thing the Republicans don’t want to do: authorize an increase in the debt ceiling. Trump has to know this, and yet this week he derped his way into forcing the Republicans to vote on a debt-limit increase more often than is politically acceptable.

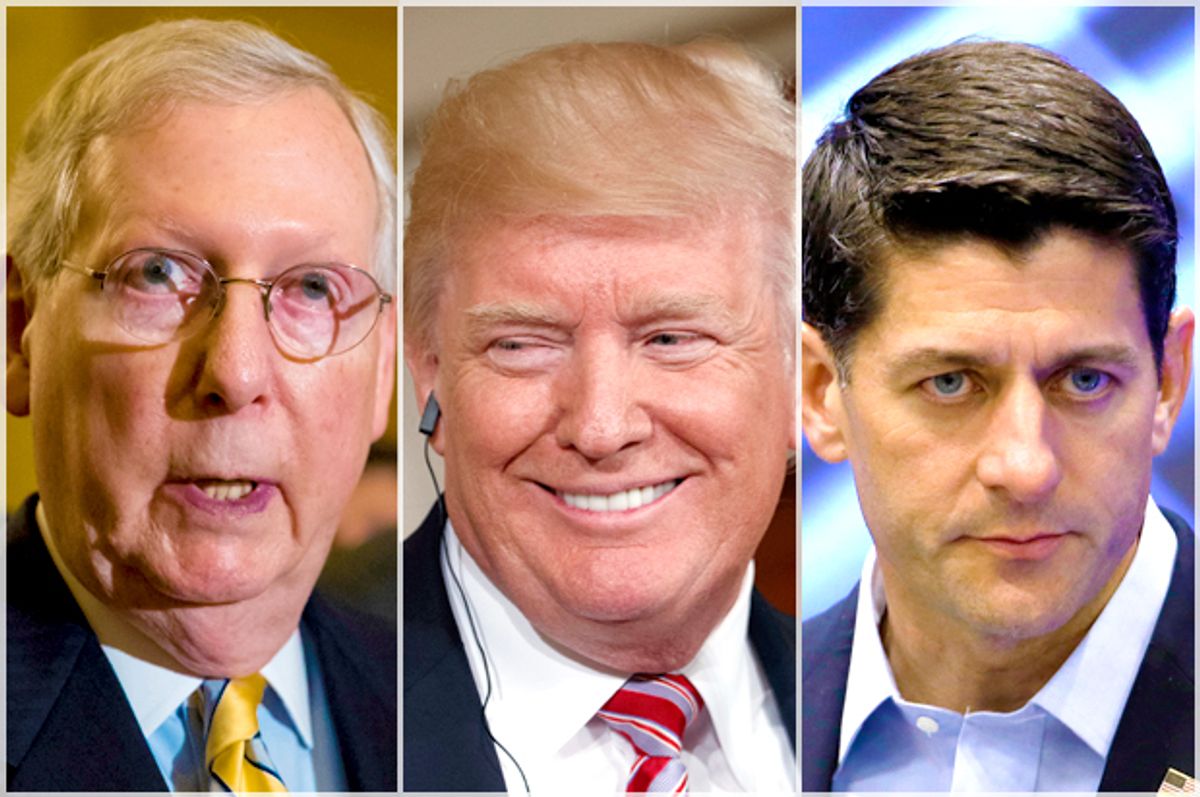

On Wednesday, Trump held a high-level meeting in the Oval Office with Speaker Paul Ryan, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin. Oh, and Ivanka Trump apparently made an appearance, to the alleged chagrin of McConnell and Ryan. That aside, the upshot of the meeting was that Trump inexplicably cut a deal on the spot with Pelosi and Schumer in order to fund Hurricane Harvey relief efforts, continue to fund the government and raise the debt limit for another three months.

Why are the Republicans so miffed?

Trump made a short-term deal which means that instead of waiting to raise the debt ceiling again in 18 months, as Mnuchin had suggested, Congress will have to do it now and then do it again in three months. In other words, instead of waiting until after the midterm elections to meddle with the debt ceiling, Republicans will have to vote on a debt limit increase twice this year, before the midterm campaigns even get underway. Members who vote “yes” on the GOP side will have to do it multiple times, putting them in an awkward position given their many years of demonizing the debt.

Furthermore, according to an analysis by Russell Berman of the Atlantic, adding a debt-ceiling vote at the end of the year will likely provide an upper hand for the Democrats on a DACA bill along with other appropriations, given that members are typically under pressure to authorize new spending before the holiday recess.

But the worst victim of Trump’s deal is probably Trump himself. First of all, he once again pissed off the two congressional leaders who are essentially the gatekeepers between Trump and impeachment. When the chips are down, Trump will need Ryan and McConnell to block the advancement of impeachment articles -- Ryan in the House, especially, while McConnell would possess a great deal of power in a potential impeachment trial on the Senate floor. Why Trump is deliberately antagonizing his two most crucial allies is beyond me, but fine.

Meanwhile, by appearing to side with Democrats, at least for now, Trump is potentially eroding his own fanbase. According to the new NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll, Trump is only “strongly approved” by around 24 percent of voters. Appearing to favor the hated Democrats could potentially erode the 16 percent of voters who only “somewhat approve.” If Trump drops below a 30 percent approval rating, it could signal the GOP to finally cut bait and walk away -- maybe even triggering some Republican support for impeachment.

Once again, Trump seems to think he’s this brilliant dealmaker, but even when it comes to the thing that’s synonymous with his brand -- the "art of the deal" -- he knows nothing. It seems as if everything he does is counterproductive to his own self-preservation. Weirdly, he doesn’t even seem to realize the jeopardy he’s put himself in by undermining the congressional leadership of his own party. The rest of us can only hope he’ll continue to bungle his way closer and closer to prosecution or impeachment or both.

Shares