Time Magazine’s selection of the #MeToo Movement as its Person of the Year for 2017 is a powerful, vindicating statement for a movement that has spread worldwide. Some may call it an obvious choice, surely, given the movement's initial sweep and effectiveness in bringing some of the most public faces of sexual abuse and harassment to justice.

The fact that its reveal under the headline of “The Silence Breakers” brought a sigh of relief and surprise, though, is indicative that the movement’s boosters have long learned to take nothing for granted. Nobody can in these disheartening days, and especially given the president’s self-serving and obviously false misdirect as to who the publication had selected.

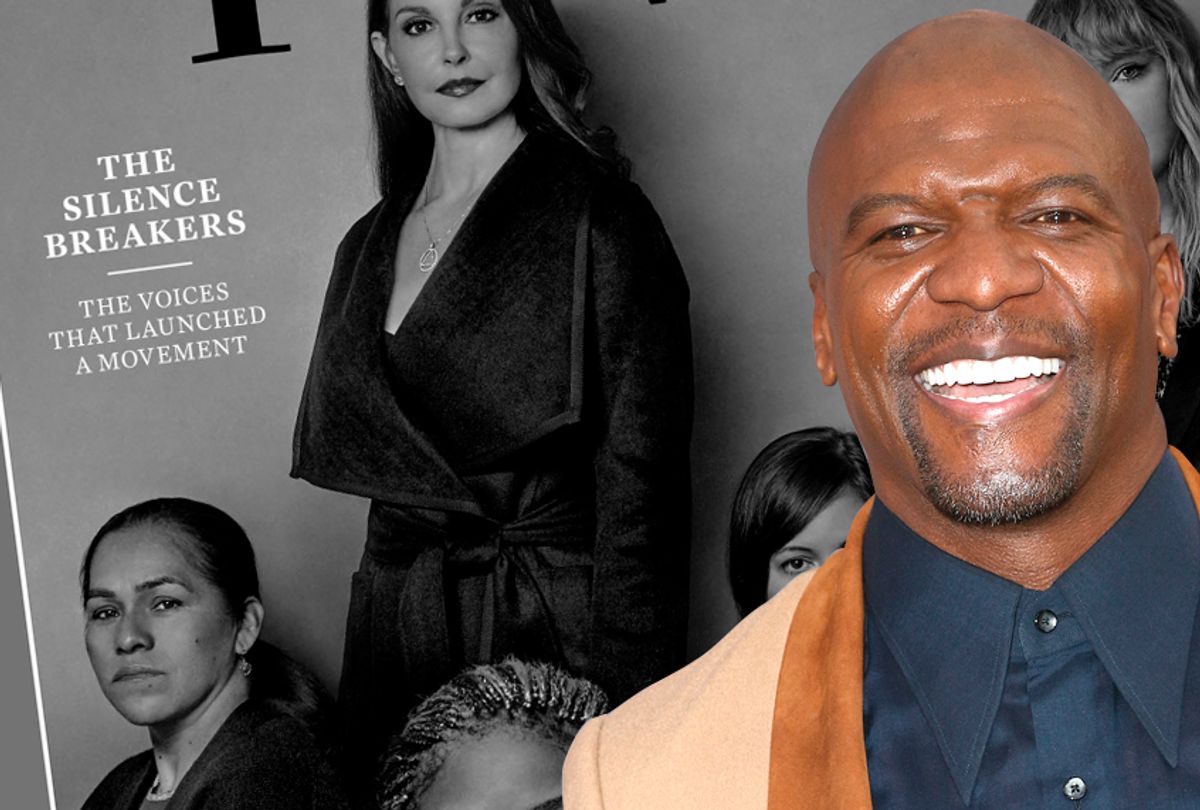

But an important aspect of Time’s coverage stood out to me right away, and it’s something that’s been missing from the majority of headlines making the broadest impact. Out of the five women featured on Time’s cover, two are women of color: Isabel Pascual, an agricultural worker, and state government lobbyist Adama Iwu. The other three are former Uber engineer Susan Fowler, actress Ashley Judd and pop star Taylor Swift.

With that image Time addresses what’s been nagging at me for weeks now — ever since the dam broke, washing away the careers of an assortment of showbusiness heavyweights. Few of the headlines have featured the stories of black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American or other actors of color. And very few people seemed to be asking why that’s the case, until Terry Crews escalated his public battle to bring his perpetrator to justice.

Time features Crews as one of its “Silence Breakers,” and his visibility in the #MeToo tsunami is essential. What’s extraordinary is his willingness to speak out as a male ally and a fellow victim of harassment and assault. Months after the first reports about Harvey Weinstein’s decades-long record of predatory behavior first emerged, the ranks of famous men publicly and passionately supporting the movement or coming out as victims remains thin. Survivors demanded to be heard and were met with the social equivalent of “Yes, but” when #MeToo was replied to by the male insecurity hashtag known as #NotAllMen.

Even so, allies are coming forth. John Oliver received passionate praise for holding Dustin Hoffman’s feet to the coals this week as he hosted a panel discussion for anniversary screening of “Wag the Dog.”

“I can’t leave certain things unaddressed,” Oliver said at the end of a sparring match that grew increasingly tense. “The easy way is not to bring anything up. Unfortunately that leaves me at home later at night hating myself. ‘Why the . . . didn’t I say something? No one stands up to powerful men.’”

Late night hosts embraced #MeToo as fodder in the same way any explosive current event feeds their monologues. Stephen Colbert took the questionable step of allowing “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” to be a stop on former “Access Hollywood” host Billy Bush’s Image Rehab Traveling Jamboree. When Bush weakly attempted to make the excuse of saying that NBC encouraged everyone, including him, to “kiss the ring” when it came to Donald Trump, Colbert countered with, “And where was he wearing the ring?”

Righteous punchlines and off-the-cuff comebacks are easy. Men assuring women they believe them has become somewhat easier except, it seems, among Republicans in Congress. Crews, a widely-known television personality currently starring in the Fox sitcom “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” is speaking out as a male sexual assault survivor — and a black man — who had remained silent until #MeToo exploded.

Crews shared his experience early on in a Twitter thread on October 10, just days after the New York Times story on Harvey Weinstein broke.

Actor Terry Crews recalls being sexually assaulted by Hollywood exec

He chose not to name his assailant at that time, but went on to name Adam Venit an interview conducted with Michael Strahan on an episode of “Good Morning America” that aired on November 15. At the time of the accusation, Venit was head of the motion picture department at William Morris Endeavor (he has since lost that title). According to trade reports his client list has included Adam Sandler, Casey Affleck and Dustin Hoffman. Crews says Venit walked up to him and grabbed his genitals, in front of his wife, multiple times during a Hollywood party hosted by Sandler.

Venit is one of the most powerful men in Hollywood. He’s also someone who operates behind the scenes.

This is part of the reason WME chose to suspend Venit rather than dismiss him, assuring ABC it was conducting an internal investigation into the matter. Perhaps WME assumed the accusations would blow over because as a black performer, Crews has less power than his white peers and the fire he started would be quashed, or he could be easily discredited.

But Crews is not satisfied to keep his battle in the court of public opinion. He filed a police report, and TMZ captured him walking out of the precinct afterward. After the news broke that Venit had returned to work, Crews filed an assault and battery lawsuit against Venit and his employer. (Crews used to be represented by WME but fired the agency after taking his story public.)

Unlike his white cohorts, the risk Crews is taking in speaking out was not immediately greeted by loud affirmation, support or, as events have proven, swift justice. Shamefully worse, talk show host Wendy Williams went so far as to say that Crews’ interview with “Good Morning America” was not brave. But what she said after that is telling and, sadly, answers the question of why we haven’t heard many specific #MeToo stories from other famous people of color.

"It may have a really negative effect on his career, do you know what I mean?” Williams said, “Being all Black and being all chatty and this agent . . . . He named names y'all.”

There you have it. The difference between being heard as a victim comes down to influence, and melanin. Of course, Crews’ story is just the latest and most public example of that.

In October New York Times readers bore witness to Lupita Nyong’o account of being harassed by Weinstein, and she could do that because by then dozens of other A-list celebrities had given their public account of his obscene, abusive and even illegal behavior. And yet, it’s Nyong’o’s account that Weinstein chose to specifically and officially deny. Not Cara Delevingne. Not Angelina Jolie or Gwyneth Paltrow. Only Nyong’o, an Oscar winner and the only black woman to accuse him on wrongdoing at that time.

And as #MeToo washes through the news industry we’re finally hearing accounts from black women who sustained harassment and abuse from their male cohorts stemming from their race as well as their gender. Adaora Udoji describes her experience working with accused NPR host John Hockenberry as “excruciating” in an op-ed for The Guardian. Udoji once co-hosted “The Takeaway” with Hockenberry, one of a line of black or multiracial female hosts who came and went that includes Celeste Headlee and Farai Chideya. In Esquire, Rebecca Carroll shared her experience of working with Charlie Rose in 1997.

“If I pushed back on anything race-related, I was silenced or punished,” she writes. She goes on to add:

"In America, the most desirable woman in the room — the most sacred, coveted, enshrined woman — has always been the white woman. As a survivor of sexual assault myself, I know that we women of color are victims as much, if not more, than white women; we are also less likely to come forward with our stories of abuse because there’s so much more at stake.”

And this succinctly speaks to the difficulty of what Crews is facing from this point forward, and it very much underscores his bravery.

We continues reel from the sheer horror of how quickly the list of public-facing predators is growing — Louis C.K., Kevin Spacey, NBC host Matt Lauer, Rose, Garrison Keillor, Hockenberry and only recently Danny Masterson. The Silence is being broken, and as Time specifies, for once the default is to believe the accusers and place the weight on the accused who are more often than not people of greater means and in more powerful positions.

But this is also a movement that activist Tanya Burke, a black woman, began in 2006 to encourage solidarity among survivors of sexual violence, mainly women.

Alyssa Milano initially received credit for its viral spread this fall, but social media quickly brought the attention back to Burke. The movement continues to evolve, and Time’s honor will doubtless help it along. One hopes that the visibility of its multiracial component can shatter the silence and bring resolution to the people who still risk much by speaking out.

Shares