Grief and trauma are rarely the dramatic, sliding-down-a-wall-in-tears experiences you see in movies. Sure, sometimes there are big, emotional outbursts. But often it's a dull but persistent numbness. Or it's intense and boring at the same — like a very long labor, when you find yourself thinking, I cannot believe how been in this howling agony for this long.

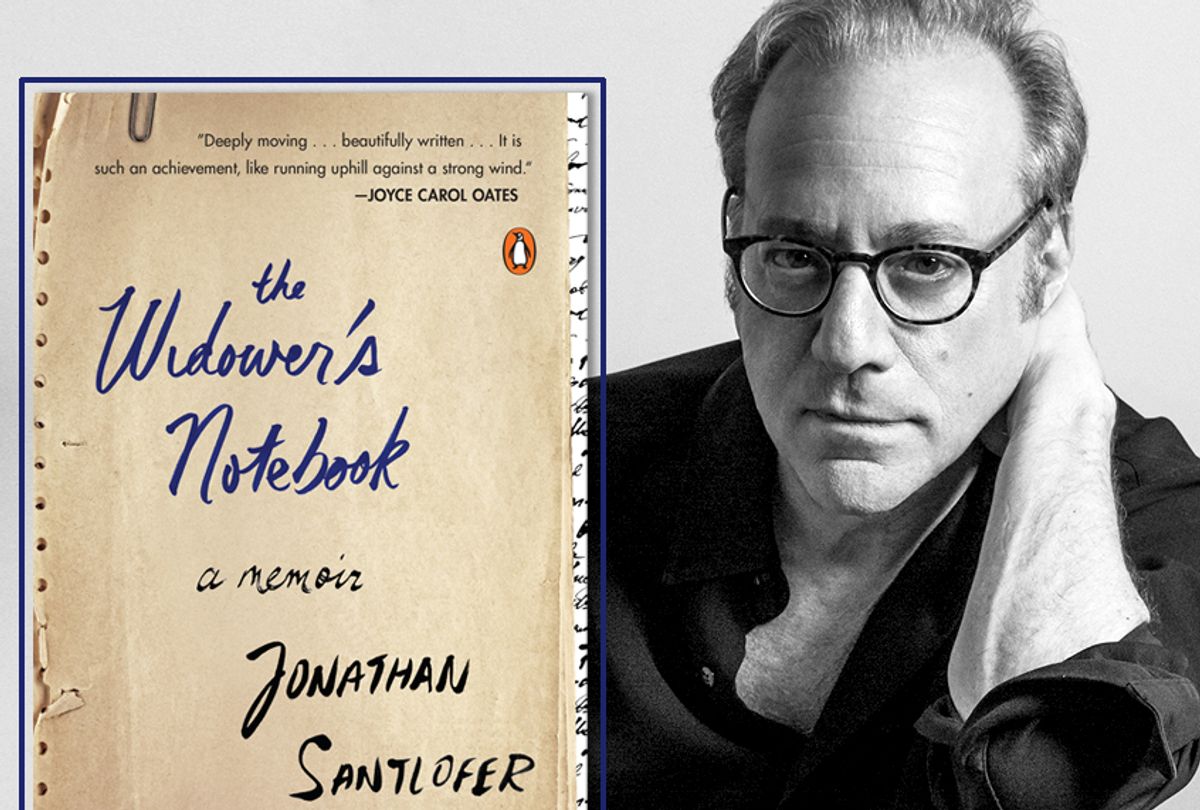

Author and artist Jonathan Santlofer learned it firsthand when his wife Joy passed away suddenly a few years ago. In his intimate, insightful and often funny new memoir, "The Widower's Handbook," he describes the otherworldly experience of watching the person you love die in your arms and the abrupt transition from one life to another. He also astutely observes the fluid experience of grief, something that does not unfold in an orderly fashion or take place in a strict time limit.

Having endured my own deluge of losses over the past few years — in addition to life-threatening illnesses for both myself and my older daughter — I know my way around the terrain of difficult experiences. Santlofer's memoir feels like a candid conversation with a patient friend, one who understands what it's really like, because he's been there too. And because he understands that, as he says in the book, "Grief was not like anything I had imagined."

"We read that there are stages," the New York writer explains during a recent phone conversation. "There are all these codified ways we're going to feel. This is, to me, it is not true at all. I describe it instead as jumping out of an airplane without a parachute. I just was all over the place. I think one of the biggest things for me was the sense of complete exhaustion." He continues, "Everyone thinks there's a shelf life to grief. Let me just point out that my wife and I, we were college sweethearts. We'd been together forever. I'm not saying we had the most perfect marriage in the world, but we had a great time together. A year after my wife died, a friend and I were out for a drink and he said, 'Are you over that yet?'"

Yeah. It's like that.

I have a friend who had a very different traumatic experience several years ago. He confessed to me recently, "It's been five years, I should be over it now." I asked him, "Why? Why should you be over it? Why should you ever be over it?" Getting over it isn't an option. You just have to figure out how to live in it, how to not let it calcify you or turn you bitter. You have to grab on to the people who show you love and remember what that feels like then when someone else is going through it. You have to learn how to sit in the presence of their experience without judgment, without trying to fix it, without anything other than unconditional acceptance. The people I care most about now understand. They are the ones who’ve had cancer, who have had their kids in the ICU, who have lost someone very abruptly. The people who are grieving, the people who are traumatized. This is my tribe now. Honestly, they're funnier than most people, and they're generous as hell.

And yet they never put it in the ads for Grief Town how absurd it often is. Some of the most farcical, hilarious moments of my life have happened deep in throes of loss and serious illness. I don't know, maybe things just seem funnier after somebody's puked all over the place. And the release of being able to laugh or joke is part the stress of it, a perfectly normal response to entirely abnormal circumstances. "I think humor keeps us human," says Santlofer. "I really do. People have told me that though my book made them cry, it also made them laugh a lot. My wife never stopped thinking I was funny." But he adds, "I think often when you do that, some people judge you in a weird way. I remember my daughter saying to me that when we had the memorial at home, she had been standing with a group of her friends laughing about something. She thought, 'How can I possibly be laughing?' Of course you are. It's the story of us, I think."

"Sarah Silverman said this thing, 'The reason why humor has to go to the darkest places is because it sheds a light on it and it makes it less scary,'" Santlofer says."It's just so smart and it's really true. It's not like I don't want to spend my time with people who haven't gone through that stuff, but I know I don't want to spend my time with people who won’t acknowledge any of that. I'm not interested. I'm just not interested."

My own evolving coping mechanisms have been vast and sometimes scattershot. The past few years, I've sought out books about the experience of loss that lift the veil on what's like inside that place. I've joined a support community. And I divide my life into befores and afters. I accept that every after is the closing of the door on that version of myself who lived in before. I have to grieve for her too, and I get now that it takes other people time to get to know the changed person as well. You can't go back to your old life, because your old life has been burned down. It's a reckoning with wide ripples.

"When you go through trauma, says Santlofer, "if you come out the other end, you're a new form of yourself in a way. I feel that I'm still that guy, but there's something intrinsic in me that has been changed and it's different. I think also that most of us don't really know how to react to people who are either ill, or who have lost someone. We don't have a culture that encourages that or teaches us that. I think it's very hard for men. Men are giving such a narrow band with emotion in our culture."

READ MORE: Women’s anger is not to be ignored: Lessons from HBO’s “Sharp Objects”

Santlofer says he felt that cultural gap, which leaves many not knowing how to react to other people's losses, personally. "I was a little tossed aside by some friends. I want to just forgive everyone. They did the best they could. It wasn't good enough for me, but I don't know that people know how to do it. I don't know why. I thought with the people who didn't show up, should I have like an engraved invitation that said, 'Show up'?"

"Maybe it is so scary to people that this is going to happen to all of us," he says. "That we're all going to lose someone. That everybody's going to die. It's scary, but it becomes less scary if we confront it. It becomes less scary if we allow the experience in. I understand when people don't want to talk about it. We want to live our lives and want to have a great time. We want to do all that stuff, but I think it makes your life richer because it makes you aware of how great life is or can be."

I've had to work hard on the forgiveness aspect as well, because some of the people who disappeared over the past few years were people my children knew and trusted. They couldn't understand why suddenly those people were gone. That's the thing that is hardest. And yet, the other side of that is the ways other people stepped up, including people who I hadn't expected. When you see how people can be there for you, be generous for you, connect with you, guide through this new world, it's unbelievable.

"The Widower's Notebook" has a clear relative in Rob Sheffield's own memoir of widowhood, "Love is a Mix Tape," and there's a passage in it that I think about all the time. It's when Sheffield, newly bereft, observes that "You lose a certain type of innocence when you experience this type of kindness. You lose your right to be a jaded cynic. You can no longer go back through the looking glass and pretend not to know what you know about kindness." And it shakes you to your core.

There are still moments now when I'm having a wonderful time, and I'll just start crying because I see the fragility of it all. How it can get taken away in an eyeblink. It's absolutely terrifying. It also makes me appreciate the beauty everywhere I find it. It makes I've appreciate all the generosity I've known.

Santlofer says, "Ralph Waldo Emerson, when his son died, wrote an essay, and said, 'Grief has taught me nothing.' That, I disagree with. I think he wrote his essay too soon. Grief does teach you things. We don't want it. Nobody asks for it, but you do learn from it. You learn how to let things in. You learn how to let things affect you. You learn that you can survive it, and that's pretty big. It gives you something to take with you, and be part of you."

Shares