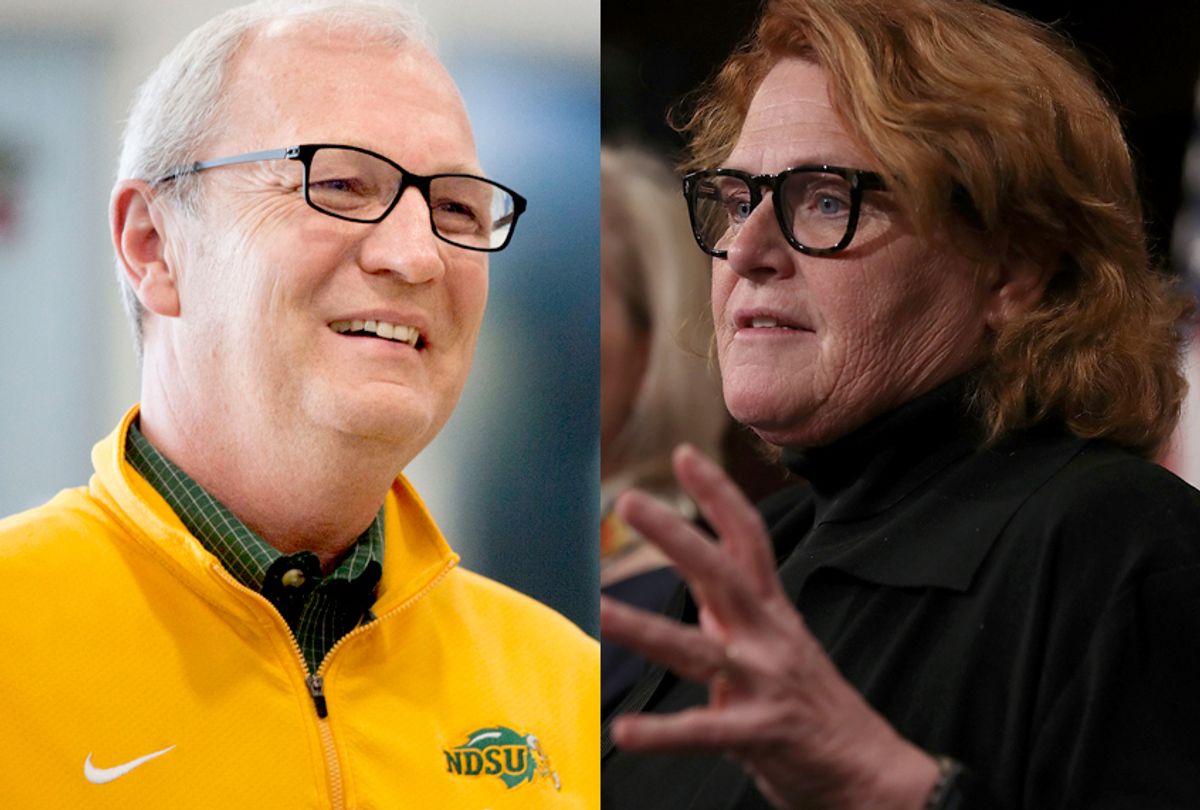

Over the weekend, Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, a Democrat from North Dakota, voted against Brett Kavanaugh's appointment to the Supreme Court, pointing to accusations of sexual assault against Kavanaugh and his grotesque behavior during the confirmation hearing. In response, her Republican opponent, Rep. Kevin Cramer, gave an especially nasty interview to the New York Times in which he ripped into Kavanaugh's accusers and slammed the #MeToo movement against sexual violence and harassment generally.

Cramer argued that voters in North Dakota reject the idea that "you’re just supposed to believe somebody because they said it happened," ignoring the significant corroborating evidence supporting accusations by Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez. Then he moved on to what I suspect his real point is, which is that women who are abused should be silent about it.

After referencing his female relatives, Cramer said, "They cannot understand this movement toward victimization. They are pioneers of the prairie. These are tough people whose grandparents were tough and great-grandparents were tough."

Needless to say, this argument contradicts the insinuation that accusers are lying. Why would you need to be tough against abuse that hasn't happened? No, what Cramer is doing is clear enough. He's painting women who speak out as whiny and weak, and women who stay silent as strong.

This argument, which is an echo of all the right-wing suggestions that the attempted rape described by Christine Blasey Ford was merely horseplay, is frankly dumb. Cramer himself made this argument, by arguing that the alleged attack "never went anywhere" and so doesn't count as assault.

First of all, calling survivors weak is false, in no small part because it's an act of immense bravery to speak out, as anyone who actually watched Ford's testimony can attest.

What's even more darkly funny is what's implicit in this argument: the idea that men are weak and need to be coddled like little children. Men are clearly too delicate to hear women's stories of abuse, so women are supposedly obliged to protect them. Apparently, abusers are entitled to have their victims keep their dirty secrets for them -- to be swathed in a luxurious blanket of female silence and protected from the harsh realities of consequences for their behavior.

A side note: This parallels the debate over the use of trigger warnings in classrooms. Opponents claim to be critical of the alleged weakness of trauma victims, but in reality they want to be shielded from the way trigger warnings remind them that others have endured trauma.

What also interests me, is Cramer's description of #MeToo as a "movement toward victimization," a phrasing which suggests that one becomes a victim not when someone victimizes you, but when you speak about it. This language illustrates the profound dehumanization of women at the heart of the backlash against #MeToo. It assumes that the experiences and memories of women don't matter. It's only when the story is told out loud, where it enters the minds of men, that it gains any relevance. This is what feminists mean by the "objectification" of women. It's not about sex so much as about this notion that women are simply objects for the use of others — like chairs or refrigerators — and not subjective people who have experiences and interior lives of value.

In other words, a woman's suffering has no relevance, so long as she is mindful not to bother men, the only people who count, by telling them about it.

That Kevin Cramer sought to put the words in the mouths of his female relatives hardly matters. They're just props being used as camouflage for what is obviously his own opinion. It's unlikely Cramer actually conducted a thorough survey of his wife, daughters, mother and mother-in-law and discovered a completely spontaneous uniformity of opinion.

Cramer's comments are offensive, but they also provide a useful way to understand the maddening contradiction at the heart of conservative arguments about Christine Blasey Ford, and about women speaking out against sexual abuse generally. Over and over again, we hear both that Republicans somehow believe Ford but also that they don't believe her; that she's credible but also that her words and evidence carry no weight. Some try to square this circle by spinning bizarre tales, based on absolutely no evidence, that Ford somehow does not know who attacked her. Others, like Donald Trump, don't even bother to come up with elaborate rationalizations for how someone can both believe Ford and not believe her.

Cramer is evidently in the second camp. He combines seemingly contradictory claims, both professing skepticism that any abuse happened and also implying that it did happen and the woman should be "tough" through silent suffering.

It's important to observe here that, in American English, the word "believe" has two separate meanings. It can be an assessment of factual evidence, such as saying, "I believe it's raining outside." Or it can be a statement about values, such as, "I believe in myself."

Take, for instance, the common sentence you hear from people in discussions about reproductive rights: "I don't believe in abortion." By this, they aren't denying that abortion is a factual thing that actually happens in the world. What they mean is they don't believe that abortion is a moral choice or they don't believe it should be legal or often just that they don't much like the idea of abortion but also would have one if they felt the need.

There's the same ambiguity around discourse about "belief" in climate change. A lot of disbelief, especially in recent years, is less about an argument with the facts than an argument about values, and about whether or not one prioritizes the planet and its people over profits for the wealthy.

By the same token, it's possible to believe that a woman is telling the truth about her experiences while also believing that she has no right to speak or no right to have her experiences taken seriously. Viewed in that light, Cramer's comments aren't a contradiction at all. His comments about being tough suggest that what he doesn't believe in is in a woman's right to testify about her experiences. Instead, he offers an alternative: Being "tough," which is conflated with being silent.

That's why, I suspect, the phrase "believe women" is taken as a provocation. It's not really a debate about facts, as feminists readily concede that no one should be imprisoned without due process or that it's OK for women to lie. It's a debate, ultimately, about values. It's a debate about whether and how much we value a woman's words, and whether a woman's truth should matter more than a man's ambitions. And for those who value the latter, it's impossible to believe in the former.

Shares