Redemption stories from people like artist and social entrepreneur Chris Wilson are worth listening to, and I’ll tell you why.

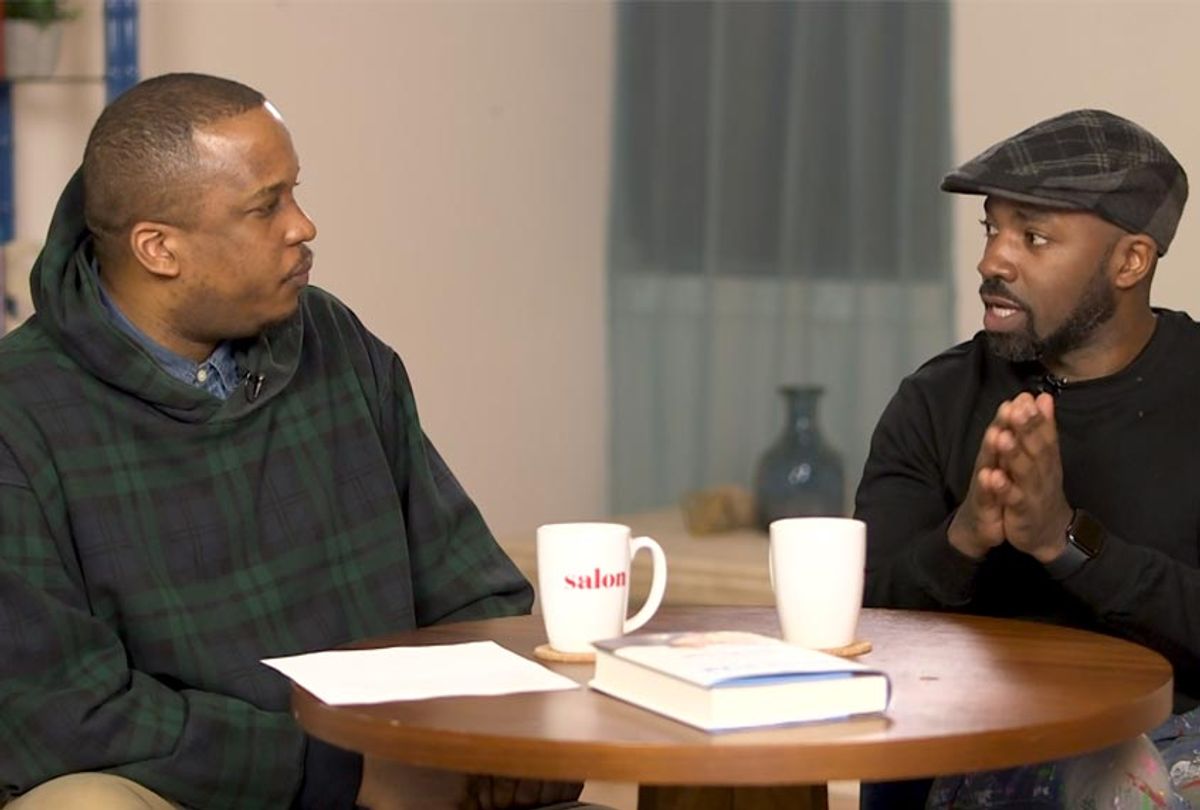

Chris sat down with me for an episode of "Salon Talks" in New York this week to talk about his new memoir "The Master Plan: My Journey from Life in Prison to a Life of Purpose," but I've been hearing about him around Baltimore for years.

The other day I sat alone in the bar across the street from University of Baltimore, where I teach, nursing a cold cup of coffee, scrolling and deleting old pointless pictures out of my phone.

Two kids rolled up and sat a few chairs down, along with a towering white guy with a big baby face and a thin black woman in her UB school store uniform. They laughed like students laughed, ordered all carbs like I did when I was teen, and talked about dating, school and my favorite topic, books.

I promise I wasn’t eavesdropping, they were loud and the spot was empty. I told myself I wasn’t going to chime in like the nosey old man with a bunch of recommendations, but the young lady said, “Chris Wilson, that activist at the school, we had a class with him, he has a book coming out!”

The guy needed a description, and the young woman did a great job—she definitely had Chris pegged—Luke Cage looking, always in a hat, shaved beard, with his painted leather jacket, and jeans that fall over his trademark Asics. “You know this guy!” she pleaded, “He’s like one of the most known guys on campus for his activism!”

“Chris is more than an activist!” I shouted out. “He’s a real dude and there’s not many around like him anymore.”

“You teach at the school, right?” the guy asked. “I was going to take your class.”

I nodded and told the kids that they should definitely run out and grab Chris’ book because he’s a rare, extremely humble, and a different type of dude. A lot of people call themselves "activists," but few are like Chris.

“Is Wilson with Black Lives Matter in Baltimore?” the guy asked. “I marched with them on North Avenue last summer.” The bartender, who knows Chris, and I bursted out laughing. A few days ago, we had a conversation about how every person with a platform has to be part of a huge social movement nowadays, or everything they do is invalid.

I don’t really eat at the bar where I sat and joked with the kids, while telling them all about Chris. The food is bad, the floors are sticky and sometimes I smell the dish rags. I only go in there because it’s across the street, they’ll put the game on if you care to ask, and the coffee is half decent. The egg sandwiches are also gourmet, but only if your blood alcohol level is whiskey.

This is also the bar where I first heard of Chris.

A few years back I was freelance writing for the City Paper, the Baltimore Sun, and wherever else would publish me, when Sam, a sharp, high-energy DJ and socially well-connected guy approached me. He liked my work, so he left the DJ booth, introduced himself, and started asking about the change makers and activist types I knew in Baltimore.

“I can’t lie to you, Sam,” I told him. “I only know a couple of writers and dudes from my block. I have zero plugs. But I’d like to make a difference.”

We laughed and he explained how a lot of those people are a waste of time, scribbled down everyone he thought I should know, and at the top of that list was Chris Wilson.

“I’ll tell you little about Chris,” I said to the kids. “Dude grew up in DC when it was known as two things, Chocolate City and the murder capital. He had it rough and was forced into the streets where he eventually had to kill someone to save his own life.”

The guy took a heavy swallow, as the girl said, “I didn’t know that was his backstory. He’s such a nice guy. I can’t believe he did that.”

Most people think you are as bad as the worst thing you have done, and that’s not true. We have to move away from that kind of thinking if we ever want to truly connect with and fully support returning citizens, and be a better country.

“While Chris was locked up,” I continued, “he completely changed his life around. He didn’t let jail kill his mind. Instead he taught himself five languages, learned some contracting and business skills, read over 1,000 books and devised a master plan for his life, so that if he was ever released, he could make a huge impact on the world.”

Chris presented his plan to the judge who sentenced him, and amazingly, he was granted freedom on the condition that he complete everything on his list. His plan had to be put into action. To date, it seems as if he has gone above and beyond.

“The book is going to be a crazy read,” the bartender added. The kids agreed.

“Those things make Chris special,” I said, “But that’s not why I said he’s more than an activist. Chris did really well as a contractor, starting his own company and making a ton of money. He didn’t just keep the cash to himself, dude started hiring returning citizens just like him, because he remembered how tough it was to find work when he first came home. And by doing that, he really made the world a better place.”

Most of the industry people I have met over the years in publishing and entertainment are all about the industry. They talk the talk, but rarely walk the walk.

Wilson’s thing has been helping some of our most vulnerable citizens find employment, and every time I call him to help, he answers and tries his best to do something, whether it was helping my friend Greg get a gig at a law firm or picking up some homies around the way to make some quick legal cash shoveling snow or moving furniture.

That’s bigger than a speech, march or an idea that never gets fleshed out — that’s real life. Poor people need to make money and Chris gets that. Recently, I was asked to write some words about Chris’ book after reading it and this is what I came up with:

Read our conversation below on "Salon Talks," or watch it here.

Tell us about your master plan.

The master plan essentially started when I was around 19. I was sentenced to life in prison, and essentially, that was like a slow death sentence for me. I knew in my heart I was a good person, and that I could do something meaningful in life, and so I wrote out kind of like a bucket list, but it was things that I wanted to do in my life, as far as educating myself, traveling the world, but also creating opportunities for other people, like in the neighborhoods that I grew up in.

You don't walk into jail with that type of mentality. You have to go through some things. Take us to the first day you were incarcerated or that first moment when you got in, and how your mindset was, and some of the things you were going through.

I was charged as an adult at 17. By the time I went to prison, I was 18. My first day, my first experience, I remember walking in the prison, and it was about 10 of us. We were all chained up. I remember them stripping us naked. They were searching us, but they made us bend over, and drop it, and squat, and cough, and they made us hold the position. Then, they laughed at us. I just remember my first experience being humiliated in prison, and there was like nothing I could do.

How do you get from that point — because I'm sure you were depressed, and angry, and just full of uncertainty — how do you get from there to a person who is able to start to imagine what life would be like outside of prison?

I was in there, you know, I fell into a depression for about a year. I met a guy who also was a juvenile who was serving a life sentence, and this guy was like super focused. He was studying to be a computer programmer. He had these goals that he wanted to get out of prison. I remember laughing at him, because like, he didn't even have a computer or access to a computer.

Eventually, he became a mentor to me, and he started tutoring me and mentoring me. He gave me the motivation to really succeed. I started by getting my high school diploma in like two months.

Your original sentence, how long was it?

A life sentence.

The guy who mentored you, he was also serving a life sentence, was he ever released?

It took him 20 years, but he was released, and he started a software company.

And it took you ...?

16.5 years

Talk about what happened up to your release date. How were you able to get that?

There was a couple things. As you can imagine, prison is like a very different place and there's a lot of crazy stuff going on. I had to figure out a way. I was 120 pounds. I had to figure out a way how to stay out of trouble, what educational resources was available to me. It was like, vocational shop, there was college, we had therapy there. I was like, "I'm going to do all these things."

Because you cannot do those things.

Yeah. It was a lot of distractions, to be honest with you. There'd be times where I'd be working towards my college degree, and it'd be my birthday, and guys would come to my cell like, "Hey, I snuck in a bottle of Remy. Let's drink," or whatever. As much as I wanted to, I had to resist the temptation, because I really believed that I would get out one day, and I knew that education would be important to me fulfilling my master plan.

The judge gave you an opportunity?

Right, I had my day to stand before the judge. It was actually 10.5 years into my prison sentence. I just was honest with her. I just talked about what led up to my crime, and how it felt, as a young man, to watch my friends gunned down in front of me, two who died in my arms. I watched my mom be raped in front of me. I talked about how remorseful I was, but also my education, and what I would do if she gave me a second chance.

What'd she say?

She just stared at me for a little bit. I just remember, like, it seemed like a couple of minutes, like she was just thinking it over.

Did you feel like you had prove something to her?

I think my accomplishments, like my degree, and all my certificates and stuff I'd done, was proof enough. I think she just wanted to hear it from me.

You have one of the most amazing success stories that has ever been talked about, studied, shared, and written. My big thing is, how do we use this book? How do we use your story? How do we use some of the experiences that you had to get to some other people to start to experience freedom, or even begin to conceptualize what freedom would look like?

That's the main reason why I wanted to tell my story through this book. The other thing that I always bring to light is that there's nothing really special about me. I'm not an anomaly. There's a lot of Chris Wilsons that are in prison. There's a lot of Chris Wilsons outside in the community. I made it this far because a handful of people saw potential in me, and mentored me, and continued, to this day, to push me, to make me believe that I could be successful. That's what I think we can do is identify the other Chrises and Christines and support them, and let them know they can be successful.

There's a stigma when we talk about jail, and prison, and returning citizens. What type of language should we be using to get more people to focus on that potential?

That's a very good question. A simple, simple solution that everyone can do, and you mentioned the word language, right, is think about the language that we use when we refer to people who come out from prison. One, I don't like the word convict. I think it's painful. I think it makes it difficult for people to re-acclimate into society.

I mean think about a child who steals a piece of candy or whatever from a store when they're young. Then, that child being labeled as a thief for the rest of their life. Like, that's what we do. We can just be more mindful of the language that we use and make it more comfortable for people to re-acclimate.

Then, there's that double consciousness. If you're going back to the society where you came from, to the neighborhood where you came from, then you have to wear that term "convict" like a badge of honor, but then when you try to assimilate, and get a job, and it haunts you.

Yeah, it's something that I'm super sensitive of. The other thing, too, is like, we need to be more conscious in voting, and calling our representatives, and letting them know what's on our mind. We got to be engaged.

Re-entry is the hot thing right now, right? [Laughs.] You got Kim Kardashian going to the White House. You got, you know, all of these big celebrities starting to take an interest in this. Are we in a moment? Or has the country finally figured out that we're jailing people the wrong way and that it's not working?

That's an interesting question. If you look at history, and slavery, Jim Crow and everything, it never really goes away. It just metamorphosizes itself into something else. Right now, we have the prison-industrial complex that's doing the same thing that slavery did to our communities in the past. I think that the machine, the system, is metamorphosizing itself into something else. I think we're fighting it. I don't know what it will become, but I think we should still keep fighting it.

I hope that people continue to have love and compassion for our returning citizens, and our brothers and sisters who are still incarcerated, because they need love, too. It's easy to forget about them.

Right, absolutely. One of the things that I've been advocating on is the importance of education behind the fence. Some people find it controversial and they say, "Why should they get a free education, when I'm paying for it?" The data supports that people who get their education in prison don't go back to prison.

Talk about when the judge gave you a second chance. You're able to come back into society. Your first day out, what was on your mind? I know you probably had a big Jheri curl, some suspenders, and, you know, your clothes from the '90s. You know what I'm saying? Cowboy boots. [Laughs.]

I actually had a big beard actually that I grew for like a year. It was strange. I remember my first day coming home, what I was most impressed or excited about was to be able to access the internet, and to go on Google, and YouTube, and just like, I could punch in stuff and just learn whatever I wanted. I was most excited about that, and then, like, good food, home-cooked meals. I spent my day just doing that, surfing the internet and eating food.

Were you doing research or just like looking at videos?

I was doing research. I remember I was doing research on learn how to tie a tie. I didn't know how to do it. I was 32. I watched a bunch of YouTube tutorials to learn how to do the Windsor knot.

You're from DC, but you came home to Baltimore.

Yeah, I was from DC, and I'd been away for 16.5 years. I come back, everything is gentrified. It's cranes up. There's Whole Foods. It's like, white people with yoga mats, and walking dogs and shit.

Was it difficult for you to come home and get a dog and a yoga mat? [Laughs.]

Yeah, everyone was just like, what do you do? Why should I be talking to you? I had done my time around a lot of people from Baltimore. I wanted to go back to school, and so I just decided to go to Baltimore.

You made it a home.

Yeah.

One of the things that I really love about you and your journey is that you always feel the need to help a lot of people who are in the business of trying to make a difference, or trying to make the world a better place. Once they get a platform, you can't get them on the phone.

Right, exactly.

You call Chris, Chris is going to show up.

Absolutely.

Is that just who you are as a person, or do you think about when you needed people and they showed up for you? Is it like a mix?

Yeah. It's definitely me as a person, but it wasn't always me. There was a point when I was incarcerated, I think about seven years in, and I was accomplishing stuff, I was staying out of trouble, and my guy who was mentoring me was like, "Look at all these guys around you." I was like, "I don't know them. I ain't get locked up with them." He was like, "Think about what you could do to help them, right?"

I started mentoring and helping folks. At this point, I still couldn't get out of prison. I kept getting denied. Once I started helping people and paying it forward, the blessings came back tenfold. It continues to be that way.

You come home to Baltimore. You don't have a job, right, but you have somewhere to stay.

Right, yeah. I was sleeping on my friend's sofa.

This is probably like the first stages of your master plan?

Yeah, first stage of the master plan. One of the things, like the first thing on the master plan, I believe, is to think about how you want to be remembered when you're not here. That guides me to be a good person even when no one's watching. Then, the second thing is, write down your plan. I knew I wanted to go to school. I knew that the number one way how you find a job is through relationships. I was like, I'm going to do really well in school and then use my professors to get a job, and that's what happened.

Then, from there, you started a company.

Yes, I started a company. I was doing workforce development in Baltimore, in the Barkley neighborhood, and employers would deny a qualified person because of a crime they committed 20 years ago.

How do you expect the person to be able to assimilate or be able to turn their life around if they can't even get a shot? How come people don't see that? We see it because we had to live it, but ...

I honestly believe people see it. Some people just don't care. We know that the system is broken, but some people think it's working perfectly fine.

Part of what you do is you create opportunities for returning citizens to be able to make money. How's that been working out?

It's been very, very rewarding. I think, to date, I've helped 272 people in Baltimore City get jobs. Less than 10 of those were minimum wage jobs. It's one of the best feelings in my life, to be able to hand someone a paycheck, and then tell them, "Look, you ain't got to look over your shoulder. You're earning an honest living." For me, that's meaningful work.

The funny thing, well, maybe not the funny thing, but the difficult thing about that line of work is every story isn't a success story.

Right.

Maybe you have 200 success stories, but there may be like 15 or 20 stories that you really wanted to work out, and they just didn't.

Right, yeah. That's the unfortunate thing about the work that I do. It's like, you can't help everyone. I struggle with that, because I'll build a bond with a person, and work with them for a couple of months, and maybe they do something stupid, or they get locked up for driving without a license, or something like that.

You've got to tell that side of the story, too. I know people who want to make a difference, and as soon as one thing goes south, they're like, "I'll go back to, you know ..."

Yeah, it's hard work. It's very tough work. You just got to just know that you can't help everyone. People got to want it. I like to help people that I see that's really working on bettering themselves. I like to give them that nudge, but there's no handouts, you know?

Right.

No one owes you anything.

Since you been home, you've also been really putting in some major work in the art world. How'd that come about?

It came about actually by accident. I was, and I do still do, design and manufacture furniture, and that kind of stuff. That's art, too. I just got introduced to this guy who was an artist, Jeffrey Kent in Baltimore. I started doing work for him. I started asking questions. He started telling me about the meanings of the art and that art was all around us.

For me, I struggle with PTSD. I had trouble sleeping, so art became very, very cathartic for me. Then, you know, I started making money.

Are you addicted to it?

Yeah, I'm hooked.

All you do is paint. You guys watching, you can't see his jeans, but like, yeah, they're covered in paint. [Laughs.]

That's right.

It's not some wild, Italian designer, you know, who staged some distressed work pants.This guy has, he puts a lot of work in. How many paintings do you in a week? I know, every time I talk to you, every time I see you, you're painting

I work on a couple. I think I work on an average of two to three paintings a week, but I probably do like 50 paintings a year, something like that, 40 to 50 paintings. I love it. I mean, I look at art as a tool, no, as a weapon to raise the consciousness of people.

How do you manage and budget your time to be able to try to save the world, get out here and sell this book, and produce 50 paintings a year?

Another thing that's a part of my master plan is, I have a team of people that I work with, and I just think about strategic stuff. I make time for things that's important. I try to paint four to five hours a night, every night, work during the day, try to read a book once a week, just try to stay focused.

You can paint, and you can write, and you give talks, and you have all of these different skills, and you said you were able to build on these skills because some people believed in you, right? There's a lot of people who can do these things if they had their shot. Can anybody come home from jail, especially spending an extremely long time there, over a decade, and be successful?

Absolutely.

Can it happen?

Absolutely.

Because you admit, you do have skills that a lot of people don't have.

Right.

Like, most people can't paint. Most people can't even hardly write their name, because we type everything. They don't even teach kids cursive anymore.

Right, that's true. That's right.

If you're making paintings, and you're doing these different things, and you're able to find success, you know, I'm always looking for scale. How can we share these skills with other people so we don't have to worry about them going back to prison? The return rate is extremely high.

I'm thinking back to when I was young, and people would try to encourage me to do stuff, but I rarely ever met or saw someone who looked like me, came from where I come from, who was successful at these things, right?

I would say to people, you got to find someone that comes from where you come from, that's successful, and kind of follow their career, but also reach out to people, you know? It's uncomfortable sometimes, but I think that we are capable of doing whatever we want to do, if we're willing to do the work to do it. That would be my advice. Just work hard, and find people who's been successful, and kind of emulate what they've done.

With that motto, then more people will start to experience success?

Yeah.

I think that a lot of people don't really understand that. You don't have to know your mentors. Oprah is my mentor, but like, I never met her. I never seen her in real life. It's not like I can text her, like, "Hey, Oprah, I'm thinking about grabbing a bagel. You want one?" You know, it doesn't really work like that, but you can have mentors that you don't know, and sometimes these people are extremely important to you and your journey.

Another thing I put in the book, too, along the lines of that, was a thing called leaving bread crumbs. As I move through life, as I make moves, I try to share as much as possible, because people are always watching. People are always following in our footsteps. I try to share that information and blueprint.

Right, and they see you sharing, and then they'll share, too.

Right.

We have an election coming up. What do you think? What would you like to hear a potential president talk about, or what type of language would you like them to use in dealing with reentry?

A couple things. I think the way we call it "correctional facilities," but most prisons or correctional facilities don't actually try to correct anything. Education would be a very big, important thing, so maybe federal Pell Grants that fund educational programs. That's been proven to reduce recidivism. That'd be one thing.

Yeah, they act like education isn't a part of rehabilitation. It's essential.

There was a success story with the First Step Act that was passed recently. That's great. A lot of people work hard on that, but that's on the federal level, and most of the people that's impacted by the criminal justice system is on the state level.

I think that needs to be addressed and that we should give more discretion to judges and prosecutors when it comes to mandatory sentencing laws. If someone has a unique case or whatever, they should be judged on an individual basis. Those would be a few things that I would be looking for whoever's running to be talking about.

Shares