As the 2020 presidential campaign revs up, the normal ways of dealing with it seem hopeless inadequate. Fact-checking seems antiquated in the face of a president who's closing in on 20,000 false or misleading statements and a press corps that remains hopelessly befuddled in how to respond.

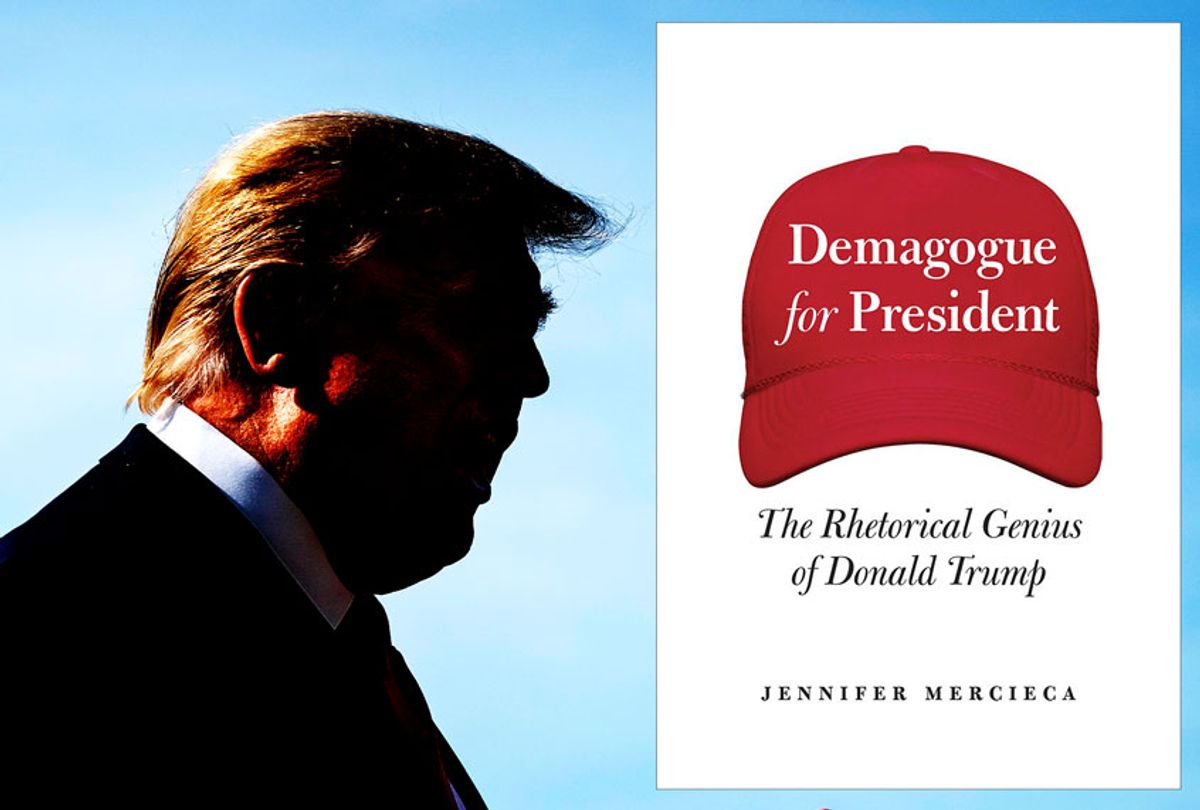

But there is another way the press — or failing that, citizens themselves — can cut through the blizzard of disinformation. That's explained in a forthcoming book by Texas A&M communications professor Jennifer Mercieca, "Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump." A historian of American political rhetoric, Mercieca traces Trump's strategies in the 2016 campaign, finding that they conform to consistent rhetorical patterns.

Trump's sheer volume of false or misleading claims is more than anyone can hope to handle, but Mercieca identifies just six distinctive patterns — three that are used to sow division in the country at large, and three that are used to unify his supporters. Some of these you already know: Trump's penchant for ad hominem attacks is impossible to miss. But for all the times such attacks have been pointed out or even decried, precious little insight has been gained into why Trump engages in them and why they seem to work — much less how he combines them with other rhetorical devices.

The reasons, Mercieca explains, were well understood by ancient Greek rhetoricians, for all that's different in our world today. Trump's aim, quite simply, is to avoid being held accountable for anything. Her book provides a coherent, objective, pro-democracy framework for seeing through his barrage of attacks on the democratic accountability he seeks to avoid. What's more, she shows how Trump used this same handful of rhetorical devices to exacerbate three key ailments of the electorate in his 2016 campaign — distrust, polarization and frustration, all of which have only worsened during his time in office.

"Demagogue for President" should be a must-read for every political reporter in America, if they hope to finally hold Trump to account. Since they may well fail to read it, all the more reason you should read it, too. My recent conversation with Mercieca, edited for length and clarity, can only server as an introduction to this book's rich insights.

In your book you distinguish between two senses of the word "demagogue." The first definition is a leader of the people, the second is a leader of a popular faction or a mob. You call the first a "heroic demagogue" and the second a "dangerous demagogue." And you note that a dangerous demagogue can't be held accountable, in part because he uses weaponized rhetoric to gain compliance, rather than using rhetoric properly as a tool of persuasion. So, what distinguishes compliance from persuasion, as a matter of principle? And what's an example of how weaponized rhetoric does this?

Rhetoric invites, it is democratic. Compliance-gaining is force, it is authoritarian. Rhetoric persuades with consent, and compliance-gaining does not. Rhetoric is addressed to people who know themselves to be addressed; it is a meeting of minds in which one person asks another person to think like they do, to value the same values, to remember or forget history in the same way. It doesn't force. It affirms human dignity by inviting. A person who seeks to persuade gives good reasons and formulates arguments in the best way they know how, always affirming that the recipient of the persuasive message has a mind, values and experiences of their own and may not change their mind. Rhetoric uses persuasion as a tool of cooperation.

Compliance-gaining weaponizes persuasion as a tool of control. The opposite of rhetoric isn't "truth," it's violence. A person may change someone's mind with compliance-gaining strategies, but because minds are changed without consent, compliance-gaining is a short-sighted strategy that will ultimately undermine the relationship between those people.

Propaganda is one example of weaponized rhetoric as compliance-gaining. Propaganda is ubiquitous in our public sphere, but most people who believe propagandistic messages don't even realize that they've been exposed to them. The producers of those propagandistic messages have denied their audience the ability to consent, to think for themselves and decide what they think is true. They've been manipulated. Typically these propagandistic messages are presented as the "real story," or "fair and balanced," or something else that's praiseworthy and democratic. Ironically, propaganda masks itself as democratic persuasion while it undermines democratic values.

You identify six rhetorical strategies that Trump used in his 2016 campaign, three to unify him with his target audience, and three to divide him from his opponents. The logical consequence, as you note, is to unify his audience against his opponents. And you lay out three conditions of the electorate that Trump exploited with these strategies: distrust, polarization and frustration. So I'd like to start by asking about perhaps the most basic unifying strategy — the ad populum "appeal to the crowd," and ask you to describe how it works generally, and then how Trump used it to exploit each of the three conditions.

An ad populum appeal could take different forms, but the basic idea is that the people are right and anyone who opposes the people is wrong. Trump uses it to praise a segment of the people: Only Trump supporters are wise and good hard-working Americans; all others are enemies. Trump claims that his supporters are the best, the smartest, the most patriotic — and then claims that their support makes him right in any controversy. It's a circular argument: Trump is right because he's popular with the good people and Trump is popular with the good people because Trump is right.

In my book I show how Trump used ad populum appeals to take advantage of pre-existing distrust, polarization and frustration and I tell the story of how and why Trump attacks "political correctness," why he said that he could shoot people on Fifth Avenue and not lose supporters, and how Trump relied on ad populum appeals to fight his way back after the "Access Hollywood" tape was released. What we learn is that Trump constantly praises his people, he declares his love for them, and he tells them that he's sacrificing for them and so they have to sacrifice for him. All of this will sound familiar to folks who know the history of fascist appeals: Authoritarians have no power without their base of support, so one of their primary appeals is ad populum.

Ad populum goes back to the Greeks and Romans, but Trump's second unifying strategy, "American exceptionalism," is both much more recent and less universal, and Trump put a very specific spin on it — particularly, as you note, by merging it with an appeal to an authoritarian constituency. Can you describe how that worked and how it benefited him?

Historians and other scholars understand American exceptionalism as "American uniqueness" — as in, America is just a different place, with a different history and values — not necessarily better or worse, just different. Politicians like Ronald Reagan presented American exceptionalism as meaning America's special role in world history to spread freedom and democracy, and critics of American exceptionalism claim that it's used as an excuse for American imperialism.

Trump uses it differently. He claims to be the apotheosis of American exceptionalism. He claims that American exceptionalism means "America winning" and that he is the greatest example of American winning in American history. He likes to explain that he was born on Flag Day, which sort of makes him America itself, then he tells fables about his leadership abilities and his business successes that make him seem like the character he portrayed on "The Apprentice."

I tell three stories about how Trump used his version of American exceptionalism to appeal to distrust, polarization and frustration: First, he used "America First" to claim that as the apotheosis of American exceptionalism he would protect American workers and bring back American jobs. Second, he used American exceptionalism to claim that he was uniquely qualified to "drain the swamp" and end corruption in America. Third, he used American exceptionalism to appeal to authoritarian voters by claiming that he would do whatever it takes to put his people back on top in America — he claimed that he was their voice and electing him would put his supporters in power.

Trump claimed to be American exceptionalism personified, but he acted like an authoritarian when he threatened protesters, had his rally crowds swear loyalty oaths to him, and violated democratic norms around the peaceful transfer of power. He claimed to be the best of America, but he ran as an authoritarian, appealing to people who didn't mind violating democratic norms if it meant that America would be "great again" — and they would be restored to their rightful place in the social hierarchy.

The third unifying strategy is a slippery one called paralipsis, which you translate colloquially as "I'm not saying/I'm just saying." It's a signature way for Trump to communicate, typified by retweeting outrageous tweets — particularly from white nationalists and conspiracy theorists — and then disavowing responsibility. But he does it so continuously ("seriously, not literally") that people have become habituated to it, without any insight into what's going on. How does this work to speak to his base and create a special bond with them?

Trump's use of paralipsis is really revealing about his whole rhetorical strategy. He uses it to say two things at once — to say the thing while he claims not to be saying that thing — which gives him the out of plausible deniability. When people ask me how I can tell that Trump knows what he's doing when he uses these rhetorical strategies, I point to the way he uses paralipsis as an example.

He tells you that he's aware that he ought not to say it — "I'm not saying this, but…" or "I don't want to say this, but…" or "It wouldn't be politically correct to say this, but…" — and then he goes ahead and says the thing that he says he knows that he shouldn't say. Trump typically uses paralipsis to spread rumor or conspiracy or to make threats or to defend violence or other despicable things, but since he has said it and also not said it, he can't be held accountable for saying those dangerous things. It's super tricky and he loves it.

Paralipsis helps Trump with his base because it allows them to see the supposedly authentic and candid "backstage" part of Trump, which helps him to appear to be an authentic truth-teller and makes them feel like they're really connected to the real Trump. It's also typically funny — the ironic twist of saying the thing that you say that you're not saying rewards Trump because people love to laugh, especially at the expense of a hated other.

How did this help him, in working with Russia, to coordinate and conspire with them in plain sight?

In the case of "Russia, if you're listening," Trump used paralipsis to ask Russia to hack into Hillary Clinton's emails and then later claimed that he was merely being "sarcastic" when he did it. He wasn't being sarcastic, but he was being ironic. He was saying and not saying. I examined the back and forth in public between Russian propaganda outlets like RT and Sputnik, Trump and WikiLeaks and found that they harvested, circulated and amplified one another's messages consistently throughout the campaign, but especially once Trump asked for Russia's help. It was all in public, no special counsel investigation was needed to see it. And the whole thing operated on plausible deniability — it could all just be a coincidence, or not.

Perhaps the best-known strategy of division is the ad hominem attack, and it's also the one that Trump uses most habitually. He attacks people so routinely that we usually neglect what his attacks are distracting us from — which, of course, is the primary point. You describe how Trump's false claim that thousands of American Muslims cheered the destruction of the World Trade Center on 9/11 got eclipsed by his attack on a reporter with a physical disability. What did Trump accomplish by changing the subject and how did that serve his agenda?

All "ad" fallacies are distraction strategies — ad is Latin for "to" or "towards" — so with ad hominem Trump is avoiding the central issue of debate and redirecting our attention towards the person who is making the argument. He might make up a nickname to direct our attention to some quality about the person that he hopes will delegitimize them in general, like "Low Energy Jeb" or "Lyin' Ted" or "Liddle Marco." He might use tu quoque (appeal to hypocrisy) to accuse his accuser, make them seem self-interested or corrupt, or claim that they do it too, so why shouldn't he? Or, he might attack how the person looks, like he did with Carly Fiorina or the women who accused him of sexual attacks.

In the case of Trump's false narrative about Muslims celebrating on 9/11, Trump used ad hominem to attack a reporter who denied Trump's version of the truth. When Trump mocked the physical appearance of a reporter with a disabling health condition it was an ad hominem attack that was meant as a parallel case. Trump claimed that the reporter's physical impairment was the same as his impaired reporting and memory of the events on 9/11. Trump's mocking behavior in front of his rally crowd was designed to shift his followers' attention away from the central question (the veracity of Trump's story) and toward the reporter's physical appearance. And it was designed to increase distrust between Trump's followers and anyone who denied Trump's version of reality. Trump mocked the reporter with ad hominem so that his followers would know not to believe anyone but him.

Trump is also known for ad baculum tactics, which means "appeals to the stick," threats of force or violence. But, as you note, though his crowds often chanted "Lock her up!" he rarely called for Hillary Clinton to be jailed himself, and only at times when he was especially threatened. One instance was following the release of Trump University documents and another was after release of the "Access Hollywood" tapes. What lessons can we learn from this pattern?

I've been studying how Trump used these same six rhetorical strategies since November 2015; he used them consistently and repeatedly. Despite what it might seem, Trump is actually restrained in how he deploys his rhetorical strategies. He holds his most aggressive rhetorical strategies back, reserving them for when his back is really against the wall. Trump is most threatening when he is most threatened, and he'll intensify his rhetorical strategies when he needs to.

Trump is always trying to win the news cycle and dominate the nation's agenda, but he doesn't always need to do that with authoritarian threats. Sometimes he can accomplish his goals with less aggressive strategies like heightening suspense and making his audience curious about what he'll do next. Sometimes he wants to control the agenda by being funny and entertaining. But when he feels threatened, like at those two moments during the campaign, he has no compunctions about resorting to authoritarian tactics like demanding that Clinton be "locked up."

But in the end, we see that it's just a ploy for Trump. He didn't mean it, Clinton had "suffered enough," he said, and she was "good people." His rally crowds led him on "lock her up" and mostly Trump didn't say it or go along with it. He used it when it served his purposes and then rejected it when he didn't need it anymore.

Since then he's followed a similar pattern of making authoritarian threats when he's in trouble and then dropping the threats when they no longer suit his needs. Is Trump really an authoritarian or is he just pretending to be one? In the end, it doesn't matter if he means his authoritarian threats or is using them for rhetorical effect because both are anti-democratic compliance-gaining strategies — both are authoritarian.

The third strategy of division you discuss is reification — in this case, meaning treating people like objects. Perhaps the best example of this is his treatment of women, whom he treats very differently depending on whether or not they are useful to him. Two things struck me about your account of this: First, that you focused on his interactions with Megyn Kelly and, second, that you drew attention to how it played with a disaffected audience he played to, including some perceptive comments by Andrew Anglin on the neo-Nazi Daily Stormer website. How do Kelly's role and Anglin's commentary help give us a more nuanced understanding of what's going on with Trump's use of reification?

I tell three stories of Trump using reification in the book: first, when he constituted Muslim refugees as a "Trojan Horse," second when he constituted immigrants as a "snake," and third when he constituted women as hated objects or useful objects. It's interesting to me that in the first two examples of reification the objects are dangerous and always hated, but with women they could be useful to Trump and therefore loved, or not useful to Trump and therefore hated objects. Women as objects are useful to Trump when they make him look good, and essentially that's all that Trump cares about. To write that story I found it really helpful to read what white nationalists like Daily Stormer and men's rights groups wrote about Trump's controversies over Megyn Kelly and the "Access Hollywood" tape.

What struck me about both of those controversies is how mainstream news and political figures (even in the Republican Party) condemned Trump's words and actions, using them as evidence that he was patently unqualified to run for president, but that Trump's messages were viewed very differently by white nationalists and the "manosphere." I tried to use that story to show how different layers of political opinion exist and while treating women as objects is nominally rejected by mainstream political discourse, the reality is that misogyny is defended and encouraged by a vocal and vicious minority. Trump is that vocal and vicious minority's president; they cheered him on when he said that he likes to "grab 'em by the pussy."

Your method in the book is to highlight each strategy in a separate chapter for each of the three characteristics of the electorate that he exploits. But as you do so, you also make it clear that the strategies overlap and reinforce each other. (Ad populum appeals build him up as a heroic figure, for example, which then justifies ad hominem attacks, even making them seem heroic, rather than cowardly.) I'd like to ask what you think is the most important example of this, so that people can have a clearer idea of how it works and what to look out for.

The strategies definitely work together and help him to take advantage of distrust, polarization and frustration, which also work together. If Trump didn't use ad populum the way that he does, he might not be able to claim to be the apotheosis of American exceptionalism, which might prevent him from using distrust and polarization as a wedge issue. He needs the support of his base to claim to be the best of America, so he uses the constant feedback loop of praising his supporters as the best of America to claim that he leads the best of America, which makes him the best of America who is uniquely qualified to lead the best of America.

It sounds odd to say it out loud like that as a strategy, but when you look at what he has done, that's exactly it. Focusing on the strategies as strategies allows you to have a bit of analytic distance from the outrage and triggering effects of his rhetoric. The strategies are all designed with the purpose of making Trump the center of all political reality, the Alpha and Omega. He wants every part of politics to be decided based on whether you support or oppose Trump.

He wants people to ask: "Do I think the economy is good?" "Should I wear a mask in public?" "Should we go to war with China?" — "I don't know, what does Trump say?" and then either agree or disagree based on Trump. He wants to be the referent for everything in politics because that ultimately gives him control. When there is no reality except for what Trump creates, he's America's authoritarian P.T. Barnum. He has succeeded in controlling our public sphere for five years, making himself the referent on all of our political discussions.

After 18 chapters analyzing what Trump did to avoid accountability in the 2016 election, your conclusion is titled "Controlling the Uncontrollable Leader." You pack a lot into a very short space there, but what would you say is the most important thing for people to take away from it?

I've been troubled by two phrases over the past five years: "the age of catastrophe" and "it's later than you think." The first is historian Eric Hobsbawm's description of the era between the Great War and World War II, a period of massive social, political, and technological transformation and the collapse of elite leadership. The second is from journalist Max Lerner, who wrote about how to reform American democracy during the first age of catastrophe.

I think that we're in a similar time and that it might be later than we think too. Lerner teaches us that demagogues like Trump are enabled by inequality and societal dysfunction. If we want to stop unaccountable leaders like Trump, then we have to remake society according to what Lerner calls the "majority principle." In 2016 we were distrustful, polarized and frustrated with our government. Trump didn't cause those conditions, but he did weaponize rhetoric to make them worse. And he's continued to do so as president.

My hope is that readers of my book will learn how and why Trump's dangerous demagoguery works so that they can defend themselves from it. But that will only do so much. The bigger picture is we need to remake our political and economic culture to prevent demagogues like Trump from ever gaining power in the first place. We need to figure out how to create trust. We need to figure out how to end polarization. We need to figure out how to end frustration. We need an economic and political system that works for the people and not for the elite. The political project of our time is to defend democracy.

Finally, what's the most important question I didn't ask? And what's the answer?

Maybe one other takeaway is that weaponized communication — dangerous demagoguery — can be (and is) used by people other than Trump. These strategies aren't new. Many of them are described by Hitler in "Mein Kampf" and have been used by authoritarians throughout world history. That Trump is so successful with these strategies is, in some ways, a bit of a fluke. If his career hadn't been redeemed by "The Apprentice," landing him a regular "Fox & Friends" gig, he wouldn't have had the widespread name recognition and he wouldn't have seemed like a strong leader who should be president.

But also, these strategies worked for Trump because he is absolutely defiant. He can't be shamed, and he won't back down. He was able to implement these strategies successfully because of those qualities. Another person would have admitted that they were wrong and quit. Trump refuses community censure, which tells me that he rejects communal norms. It's obvious in his rhetoric that he rejects communal norms, but he told us not to pay attention to that. He said it was just "women's issues" and "political correctness" and the way that he talked didn't matter. The way that he talks does matter and it tells you exactly what kind of "leader of the people" he is. Trump is a dangerous demagogue.

Shares