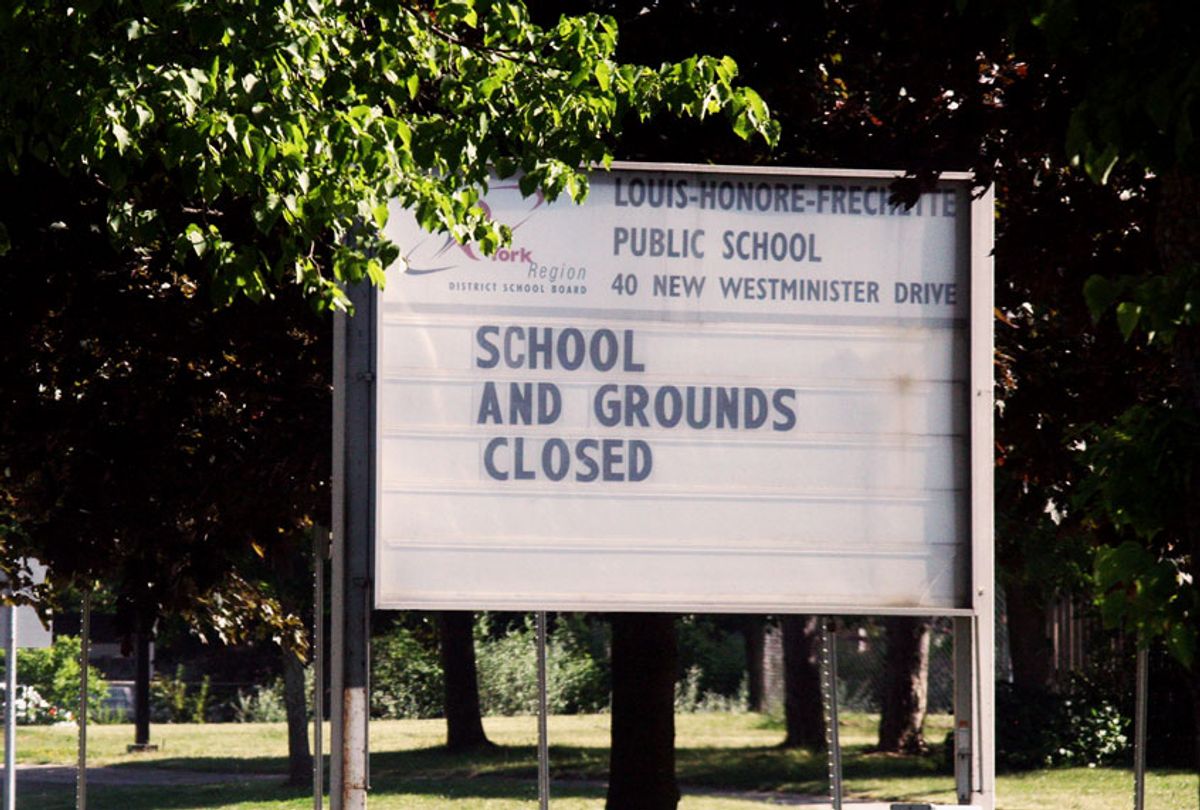

Schools across the country, amid pressure from the Trump Administration to fully reopen schools this fall, are in the throes of making a decision that will likely have consequences lasting beyond the 2020-2021 school year.

This week, the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) announced that students will not return to the classroom when the fall semester begins in August because of the surge in coronavirus cases. This decision came after United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), the union which represents LAUSD teachers, announced over the weekend that 83% of 18,000 members who took part in a poll voted against physically reopening schools to students.

The San Diego Unified School District also announced that the fall semester will begin virtually. It wasn't that long ago, however, when San Diego officials had announced a "detailed plan," developed in consultation with public health experts, to send kids back to school by the end of August. These decisions follow similar ones made in Nashville and Atlanta. Some major U.S. cities like Miami and New York City are still deciding whether or not students should physically return to the classroom this fall.

As my colleague Andrew O'hehir wrote, the decision to reopen schools is akin to "a 'Deer Hunter'-style game of Russian roulette, played blindfolded under conditions of complete chaos." Nobody knows what the best decision is – for students, for teachers, for other school employees, for guardians at home – and any decision made certainly comes with its own set of pitfalls. Moreover, like most of the fallout from this pandemic, the burden of each decision will be largely carried by working-class families and communities of color.

The health of the various parties is naturally one of the biggest concerns, but the existing inequalities schools districts face is also a factor that could have major consequences for the resources and quality of education for students.

"Districts with more resources are likely going to be able to avail themselves of higher quality instruction, and higher-income families are going to be much better positioned to support [remote] learning than less-resourced families who don't have the privilege of staying at home," Janelle Scott, an education and African-American studies professor at the University of California, Berkeley, told EdWeek.org.

Indeed, education researchers, teachers, and academics are concerned that continued online learning could further widen existing academic achievement differences between students from households of differing incomes.

"Between high-income and low-income schools, as well as between rural and all others schools, there are big technology gaps, and where there are big technology gaps it means that less students are going to be getting access to remote learning," Dr. Megan Kuhfeld, a senior research scientist at the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA), a not-for-profit organization that creates academic assessments for students pre-K-12, told Salon. "If we have a group of students who are getting access and a group who aren't, we just have to assume that that's going to widen inequality."

Access to technology is key to successful online learning, and not all families have easy access to laptops and the internet. An estimated 35% of low-income households with school-aged children don't have high-speed internet, according to Pew Research Center data. For middle-class and affluent families, an estimated 6%of households with school-aged children don't have high-speed internet.

In April, NWEA's Collaborative for Student Growth Research Center released research suggesting that this disrupted school year could result in students returning to school next fall with "63-68% of the learning gains in reading relative to a typical school year and with 37-50% of the learning gains in math."

"These preliminary forecasts parallel many education leaders' fears: missing school for a prolonged period will likely have major impacts on student achievement," the researchers wrote. "While we are unable to account for students' exposure to virtual instruction while schools are closed, our learning loss projections imply that educators and policymakers will need to prepare for many students to be substantially behind academically when they return."

These lack of educational gains are more likely to be seen in children in early grades, and among those already facing inequities. Researchers at the Brookings Institution suggest that students might be substantially more behind in mathematics.

"Thus, teachers of different grade levels may wish to coordinate in order to determine where to start instruction," the researchers wrote. "Educators will also need to find ways to assess students early, either formally or informally, to understand exactly where students are academically."

Kuhfeld told Salon if the pandemic was over, and students were returning to the classroom as usual this fall, educators could have played catch-up.

"If the fall was going to reopen as normal, I would say I think teachers can meet their students where they are," Kuhfeld said. "I think if this continues throughout the fall and winter where some kids are receiving no instruction and other kids are kind of getting, maybe not quite as typical, but closer to typical instruction, I think these gaps can be pretty large and consequential.

"It'll be hard to find ways just within a normal school year to catch up from that," Kuhfeld continued, adding that improving access to technology and the internet should be a priority among school districts and for policymakers as they consider education budgets.

"If kids don't have access to their teachers virtually then it's gonna be really challenging for learning to happen," Kuhfeld said.

Shares