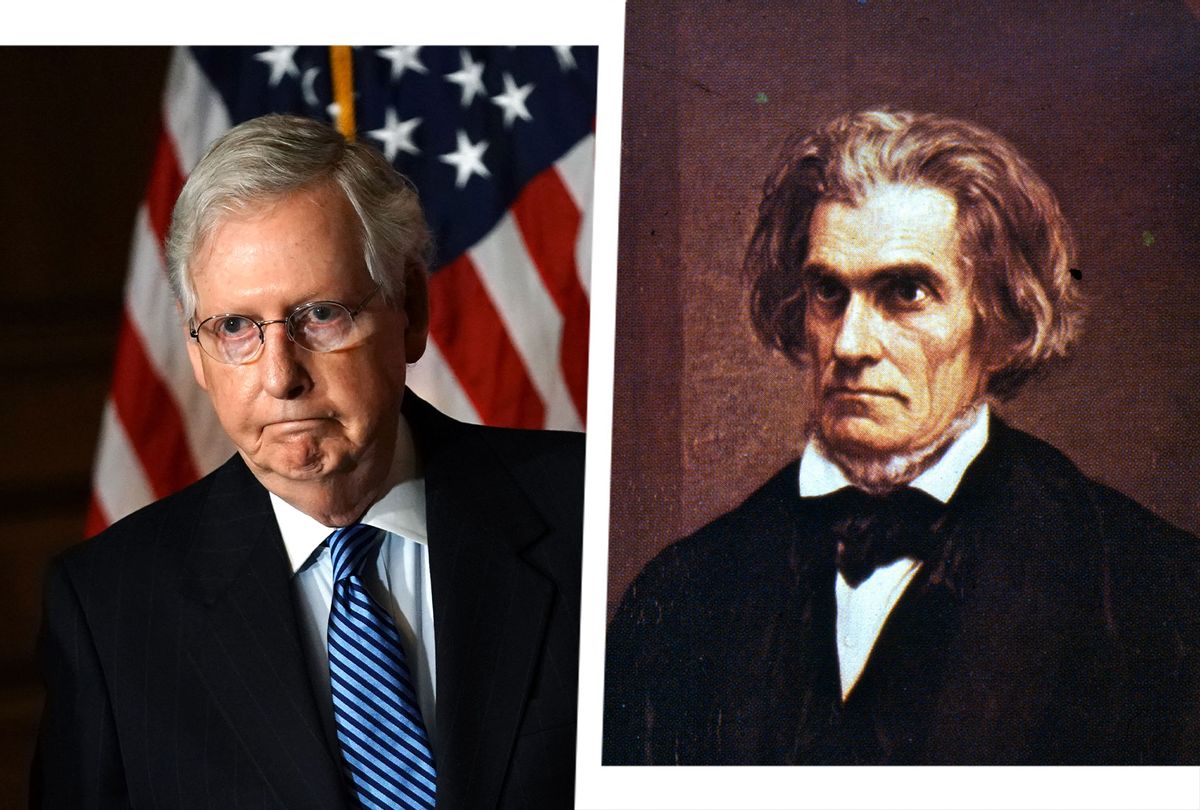

Mitch McConnell's claim that "the filibuster is the essence of the Senate" has been tossed aside by his opponents as bad history, violently inconsistent with how Jefferson, Hamilton or Madison aimed to structure the Senate, and perhaps even unconstitutional. All true. But what McConnell's screed should remind us is that the filibuster has always been the essence of the politics of white supremacy — even as it now poses a broader threat to democracy itself.

McConnell draws on a playbook stretching back to John C. Calhoun, who as vice president in 1841 forged the filibuster into a conscious instrument to block majoritarian democracy as part of his project of creating a durable framework for slavery in a nation he knew would eventually vote against it. Calhoun, generations of Southern senators and now McConnell have shared a determination that majority votes should not be the last word in the United States. Privileged minorities should be able to override the will of the entire people — if their interests are endangered. Yes, Calhoun was focused on slavery and race, but his first filibuster was over national banking. The interest he sought to protect from a national majority was that of the South as a region, extending beyond slavery to issues like tariffs.

Chuck Schumer's attempts to shame McConnell for being anti-democratic — by seeking to shrink the electorate instead of persuading it — thus land flat on the right. McConnell is tapping into one of conservatism's deep obsessions: How can America avoid majoritarian democracy? And Calhoun, who was twice vice president and twice almost president, devised the precise answer that McConnell is deploying today. When McConnell refers to "consensus," he doesn't mean compromise that generates broad acceptance across divergent perspectives within a single electorate. He means that certain important subgroups — such as those who owned human beings as chattel, in Calhoun's day — should be allowed to veto legislation, however large the popular majority that favored it. Jefferson had asserted, "It is my principle that the will of the majority should always prevail" but Calhoun twisted this by asking, "Which minority cares the most?"

White supremacists have always been the exemplar of such a protected group. Calhoun devised his doctrine to protect them, calling such a system "concurrent majorities." (He envisaged them as interest groups, not political parties — his major difference with McConnell.)

Calhoun passed the torch to the leaders of the secession movement who then rooted the theory of the Confederacy in the soil of concurrent majorities. The Confederate constitution was thoroughly imbued with Calhoun's doctrine. As the Civil War drew to an end, Jefferson Davis made clear that he would not accept majority rule: "We seceded to rid ourselves of the rule of the majority…. Neither current events nor history shows that the majority rules, or ever did rule."

After the Civil War, the Reconstruction Amendments were intended to make America a democracy where the male majority ruled, regardless of race. This vision was subverted, using Calhoun's example, by repeated Senate filibusters blocking legislation to implement civil rights, a power specifically granted Congress by their authors. The justification? That "states" were a protected minority entitled to nullify majority decisions — in other words, the very issue that the Civil War was supposed to have settled!

The deep logic of filibuster and "concurrent majority" theory alike is the grant of white minority rights denied to an African-American minority. Carrying out Calhoun's theory as he envisaged requires deciding, a priori, that one race is entitled to greater deference than the other. (This exact logic led the Supreme Court to conclude, in the infamous Dred Scott decision, that to sustain the rights of slaveowners it was unavoidable to declare that Americans of African descent had no rights at all.) On matters of racial justice, defenders of the filibuster have always argued that reducing current inequalities between two groups required a supermajority, while sustaining inequality required only a robust minority.

White supremacists sustained this doctrine throughout the 20th century. Civil rights bill after civil rights bill went down in the Senate, throttled by the filibuster and defended with the argument, as Mississippi's Theodore Bilbo put it, that "a mob is a majority; without the filibuster the minority would be at the mercy of the majority." Bilbo's fears, of course, were not for the rights for the majority of Mississippians — the state was still 50% Black, and during the Jim Crow period African Americans had been a majority. The all-white political structure was the minority whose concurrence Bilbo demanded.

The broader conservative application of the concurrent majority concept was most clearly articulated by the John Birch Society after World War II with its singular focus on one goal: "America is a Republic, not a democracy. Let's keep it that way." But outside the South, ideological conservatives were too few in the Senate to otherwise abuse the filibuster.

The conventional wisdom after 1965 was that the debate about white supremacy — and the stain that most Americans thought it had laid on our national identity — had been ended by the civil rights movement, specifically the passage of the Voting Rights Act. But while explicit arguments for restricting access to the franchise by ethnic minorities, the poor or immigrants largely vanished, stripping the filibuster of its obvious racist identity actually made possible its contemporary weaponization.

Insisting on a Senate supermajority had been a challenging, expensive and rare option almost exclusively put in play to defend Jim Crow and white privilege. Now it became a strategic but routine Senate procedure, first deployed by Bob Dole to hamstring the Clinton administration and then by Harry Reid against George W. Bush. Finally, with Obama's election, Mitch McConnell unleashed the full force of the 60-vote loophole and imposed upon the Senate the very supermajority the founding fathers had specifically rejected. The toxin that Calhoun had first injected into the Senate to counter the future threat of majority rule now found its moment. The virus spread.

While the filibuster — the essence of Mitch McConnell's Senate — is the most powerful weapon the right-wing opponents of democracy have seized, Republicans in 2020 are deploying the full panoply of anti-democratic strategies devised over two and a quarter centuries by Calhoun's followers. The most important campaigns being waged by conservatives at this moment emphasize the spread of gerrymandered districts, purged voter rolls, legalized bribery, a politicized judiciary, state pre-emption of local home rule and crippling the executive authority of majoritarian governors, even Republican ones.

Every tool is designed to reduce the ability of the majority to govern. Changing voting rules or Senate processes such that the minority can prevail over the majority is a feature, not a bug. If endless voting lines in minority precincts in Georgia creates an opportunity to influence voters by offering them water, why else is the solution to make offering water a felony, rather than offering those citizens adequate numbers of voting booths?

Yes, the motivations may be — as some Republicans conceded in a Senate hearing last week — that if every American could vote easily, Republicans would lose because they are a minority. But Schumer's complaint about derailing majority rule, for many conservatives, misses the point. Some on the American right doesn't think the majority deserves to rule. Even more of it believes that voting and participation in governance are privileges to be earned, not rights to be protected. That's their understanding of "the consent of the governed." Mitch McConnell now has the Senate that John Calhoun always schemed for. That is the dilemma facing American democracy.

Shares