On March 25, the Georgia state legislature passed a now-infamous Republican-backed bill that introduced a series of stringent voter restrictions under the auspices of "election integrity." The bill (SB 202), which Democrats across the board have described as a grievous violation of voting rights, limits the number of drop boxes, reduces the time allowed to request a ballot, bars election officials from sending out mass absentee ballot applications, and criminalizes the practice of handing out food or water to voters waiting in line, as PolitiFact reported this week.

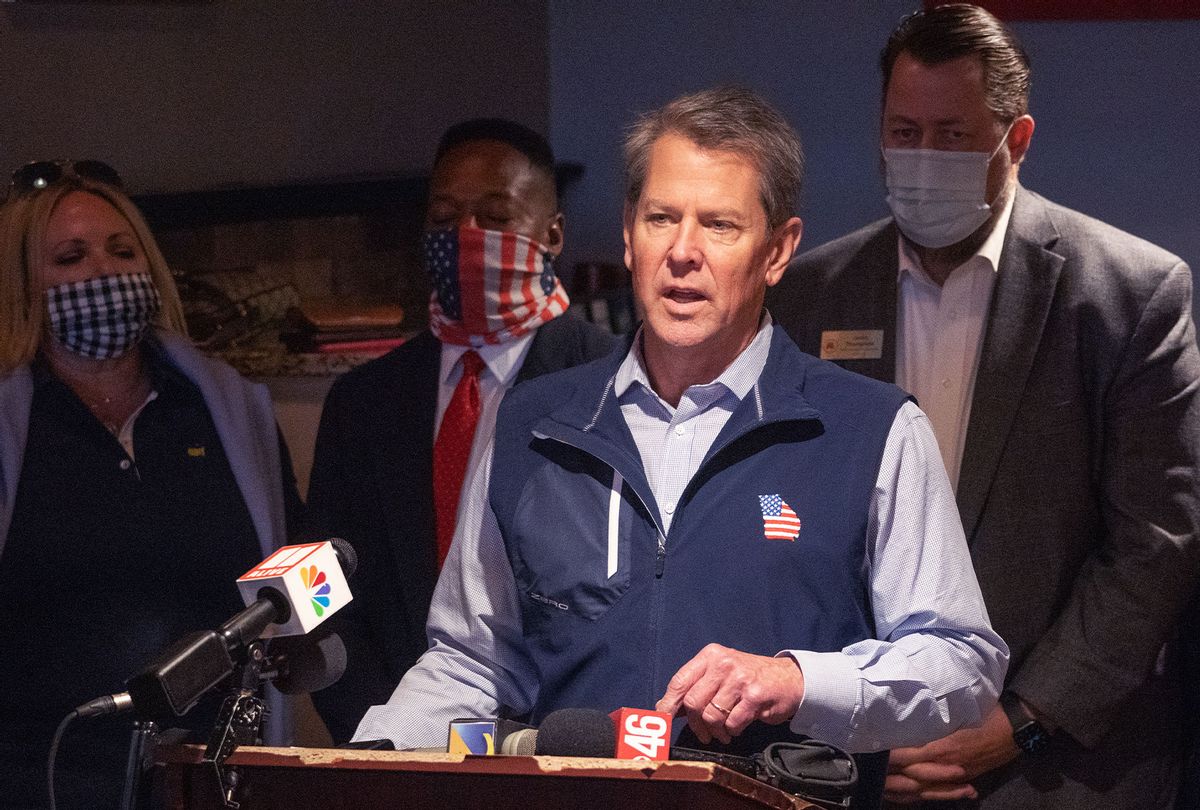

Democrats raged against both the state's legislature, as well as against Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican apparently trying to rebuild his reputation in his own party after resisting former President Trump's attempts to overturn the 2020 election results while the bill was in transit. But just as much ire was directed at corporate America, which appeared to stand on the sidelines as Peach State lawmakers propelled the bill forward. Among those most criticized were big Georgia-based companies like Coca-Cola, Delta Airlines, AT&T and Home Depot.

Facing enormous pressure to take a stand against the bill, two of these institutions (Coke and Delta) have recently spoken out against SB 202, while another of them spoke about the importance of voting rights more broadly. Reports show that over the past several years, however, every single one of those spoke very differently with their political donations.

According to CNBC's Brian Schwartz, since 2018 Coca-Cola has contributed more than $25,000 to Kemp, as well as to the bill's state Senate backers. Salon found in company filings, for instance, that thousands of dollars in 2020 were donated via Coke's Georgia PAC to state Sens. Michael Dugan, Frank Ginn, Chuck Hufstetler, John Kennedy, Jeff Mullis and Blake Tillery, along with state Rep. Barry Fleming, all of whom sponsored the widely-criticized bill to clamp down on voting access.

Coke also made a corporate donation of $172,000 to the Georgia Political Action Fund. According to Georgia state campaign reports, the "The Coca-Cola Company Georgia Political Action [sic] Fund" — almost certainly the same entity — gave $4,000 last year to Kemp's 2024 primary campaign. It also gave thousands to the aforementioned Hufstetler and Mullis, along with Sens. Dean Burke and Butch Miller.

Asked to comment on its relationships with these lawmakers, a Coca-Cola representative directed Salon to CEO James Quincey's official statement on the bill, which states that "throughout Georgia's legislative session, [Coke] provided feedback to members of both legislative chambers and political parties, opposing measures in the bills that would diminish or deter access to voting." So while the company claims it worked behind the legislative scenes to remove the most objectionable provisions of SB 202, Coke concurrently bankrolled sponsors who were probably responsible for those very provisions.

Asked whether the bill's passage will inform the company's future political giving, a Coca-Cola spokesperson emphasized that it had "suspended all political contributions in January after the incident at the U.S. Capitol."

That "pause" is still in place, the spokesperson added, declining to provide a timeline for the potential resumption of political donations.

Delta Airlines, another Georgia-based company that has spoken out against the bill, has a similarly deep history of backing the bill's most ardent supporters. According to CNBC, Delta has given more than $25,000 to Kemp and the bill's sponsors. Slate estimated that this number may in fact be north of $41,600.

According to Georgia state filings reviewed by Salon, in 2020, Delta gave thousands to Dugan, Miller and Mullis through its corporate PAC. It also donated $15,000 to the Georgia House Republican Trust, a fund run by the Georgia House Republican Caucus, which has routinely counterattacked Democratic criticism of SB 202. As one of its Facebook posts claimed on Tuesday: "The attack on Georgia's SB 202 Election Law and the Senate Filibuster are just ways for the Liberals to use the rhetoric of 'racist' and 'Jim Crow' to justify the federal election takeover of HR 1 to pass through Congress." Delta also gave $15,000 to the Georgia Republican Senatorial Committee, which, according to its annual registration from 2015, is run by state Sens. Steve Gooch and John Wilkinson, both of whom voted yes on the voting-restriction bill.

Salon was referred by a Delta spokesperson to CEO Ed Bastian's March 31 statement expressing his dissatisfaction with the final legislative product. "Delta joined other major Atlanta corporations to work closely with elected officials from both parties, to try and remove some of the most egregious measures from the bill," he said. "We had some success in eliminating the most suppressive tactics that some had proposed. However, I need to make it crystal clear that the final bill is unacceptable and does not match Delta's values."

But according to a tip from a purported Delta insider to MeidasTouch's Ben Meiselas, the airline previously praised SB 202 and released an internal statement on March 26 saying that Delta's "voice was well represented and well heard." A quote from Bastian in the memo explained that the legislation had "considerably improved" because of Delta's intervention. Kemp said later that Bastian's follow-up statement on March 31 stood "in stark contrast to our conversations with the company." He said, "At no point did Delta share any opposition to expanding early voting, strengthening voter ID measures, increasing the use of secure drop boxes statewide, and making it easier for local election officials to administer elections — which is exactly what this bill does."

Bruce Freed, president of the Center for Political Accountability, told Salon that companies like Coca-Cola and Delta are reckoning with a "new world" of public scrutiny when it comes to political spending. "The murder of George Floyd; the insurrectionary attack on the Capitol; the refusal of 147 senators and House members to accept the outcome of the presidential election: All of these things have made political spending a major hot button issue that people react to viscerally," he said. Major companies like these with powerful competitors, he noted, are growing increasingly wary over their political spending, since it has the potential to sway loyal customers.

AT&T, another Georgia-based company in fierce competition for cell-phone users with Verizon, T-Mobile and Sprint, also issued a statement following SB 202's passage, this one released April 1 and attributed to CEO John Stankey:

We believe the right to vote is sacred and we support voting laws that make it easier for more Americans to vote in free, fair and secure elections. We understand that election laws are complicated, not our company's expertise and ultimately the responsibility of elected officials. But, as a company, we have a responsibility to engage. For this reason, we are working together with other businesses through groups like the Business Roundtable to support efforts to enhance every person's ability to vote. In this way, the right knowledge and expertise can be applied to make a difference on this fundamental and critical issue.

It's fair to say that statement does not make clear where AT&T actually stands on SB 202. Although the company noted that elections should be "free, fair, and secure," those qualities were never clearly defined relative to Georgia's election laws, either now or previously.

As with Coca-Cola and Delta, AT&T's press statement may be meant to distract public attention from less overt ways the company has spoken with its wallet. According to a report recently published by progressive think tank Public Citizen, from 2015 to 2020 AT&T poured $259,950 into 26 voter suppression bills proposed by the Georgia state legislature, including SB 202. The company has donated generously to SB 202 sponsors Mullis ($15,900) and Miller ($13,600) as well as various legislators who supported the bill's ratification, such as Sens. Stephen Gooch ($10,900) and William Cowsert ($14,200) and Rep. Jan Jones ($14,200). A CNBC report found that the company has also donated to Kemp's campaign.

More recently, AT&T's disclosures show that through its Georgia PAC and direct donations, the company gave thousands in 2020 to at least three SB 202 sponsors, as well as giving $15,000 to the Georgia Republican Party, $30,000 to the Georgia House Republican Trust and $18,500 to Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan ($18,500), who is said to have "paved the way for SB 202," according to Fair Fight Action, a nonprofit voting rights advocacy group founded by Stacey Abrams.

AT&T did not respond to Salon's request for comment.

Home Depot, another Georgia-based company, has spent tens of thousands of dollars to support Kemp, along with many of the aforementioned lawmakers. A spokesperson for the company told Salon that it "believe[s] that all elections should be accessible, fair and secure and support broad voter participation. We'll continue to work to ensure our associates, both in Georgia and across the country, have the information and resources to vote."

Home Depot declined to acknowledge its relationship with any Georgia GOP lawmakers who supported the bill, however, and declined to comment on whether the passage of SB 202 will affect the company's future political spending, instead saying that its donations do not reflect a partisan bias. "Our associate-funded PAC supports candidates on both sides of the aisle who champion pro-business, pro-retail positions that create jobs and economic growth," a company spokesperson claimed. "As always, it will evaluate future donations against a number of factors."

Other firms that donated to supporters and sponsors of the bill include UnitedHealth Group, Southern Gas Company, Comcast, Walmart, General Motors and Pfizer.

Daniel Weiner, deputy director of the Brennan Center for Justice told Salon that corporations must be held responsible for every political donation they make, even when they give to both parties. "Making a political contribution is a public political act," said Weiner. "When you do that, you're saying broadly that you want the recipient in office. You can't really then turn around when they do something you don't like, and say, 'We have no responsibility for that whatsoever.'"

There is no evidence that any of the corporations discussed here directly advocated for SB 202's passage. But "if [companies] want to spend money on politics," Weiner explained, "they have to accept that they're going to be judged on the outcomes they make possible — not their intent."

Various reports have suggested recently that the heightened scrutiny directed to corporate donations may lead more firms to dark money channels, which can render anonymous effectively unlimited amounts of money spent on politics. While most dark money spending is dedicated to federal candidates and campaigns, there is nothing stopping corporations from employing it at the state level.

In late March, for instance, it was reported that an Atlanta-based dark money group called Proclivity paid $550,000 to committees that bolstered the campaigns of several sham candidates in three Florida Senate races. As Politico reported, these candidates appeared to be on the ballot entirely to siphon off votes from Democrats.

In West Virginia, dark money groups contributed millions of dollars to the state's Supreme Court of Appeals races in 2020. A report by Sludge found that a sizable chunk of these contributions originally stemmed from corporate donations by companies like Marathon Petroleum and Koch Industries looking to prop up Republican candidates.

Dark money also abounds in Oklahoma. According to KGOU, between Aug. 25 and Nov. 3 of 2020, about $961,400 was spent by dark money groups on 101 seats in the Oklahoma House of Representatives and 24 seats in the state Senate. Much of this money was spent by Oklahoma MAGA, a dark money group that pumped $292,950 into pro-GOP and anti-Democratic campaigns in two Tulsa-area races. Dark money groups like the Advance Oklahoma PAC, Advance Oklahoma Fund, Americans United For Values and A Public Voice also spent thousands of dollars in the Sooner State.

The influence of dark money on state races is not purely anecdotal; the data supports it as well. According to a 2016 report by the Brennan Center analyzing Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Maine, and Massachusetts, "On average, only 29 percent of outside spending was fully transparent in 2014 in the states we examined, sharply down from 76 percent in 2006."

While dark money in state races abounds, the traditional PAC model of political spending still reigns supreme in the world of corporate campaign finance and this this was especially true in the case of the Georgia legislature.

Corporate America's role in shaping Georgia's legislature goes far beyond the relatively visible question of direct donations to candidates. For instance, according to a report given to Salon by the CPA, in 2020 46 major corporations donated nearly $17 million to the Republican State Leadership Committee, which works to elect GOP candidates to state offices throughout the nation. The RSLC directed $144,700 of that funding — through its PAC and the Georgia House Republican Trust — to 47 GOP Georgia state legislators elected in 2020. One of them sponsored SB 202, and effectively all of them voted for it.

The CPA also detailed that many large corporations donated in support of voting-restriction bills that preceded SB 202 and likely paved the way for its passage. For instance, $26,050 worth of corporate donations were raised in 2020 for state Sen. Larry Walker, who introduced SB 67, which would have made it harder for voters to access absentee ballots, according the Brennan Center. Another $17,800 of corporate cash was raised for state Rep. Barry Fleming, who introduced HB 270, a bill molded in the same spirit.

Exactly how much the national furor surrounding the passage of SB 202 will prompt corporate America to distance itself from the Republican Party in Georgia and elsewhere remains to be seen. This week, 100 corporate executives reportedly convened to discuss halting donations to lawmakers who support any anti-voting measures. Many GOP lawmakers, however, have rebuked corporations for taking sides on the issue. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., urged them to "stay out of politics." Whether "politics" includes campaign donations to lawmakers like McConnell — who has long relied on corporate support — has the potential to radically change the future of campaign finance.

Shares