Somewhere over the course of decades of fighting for the right to use birth control, and later, the right to access it from health providers, we may have forgotten to ask those who use it whether it works for them.

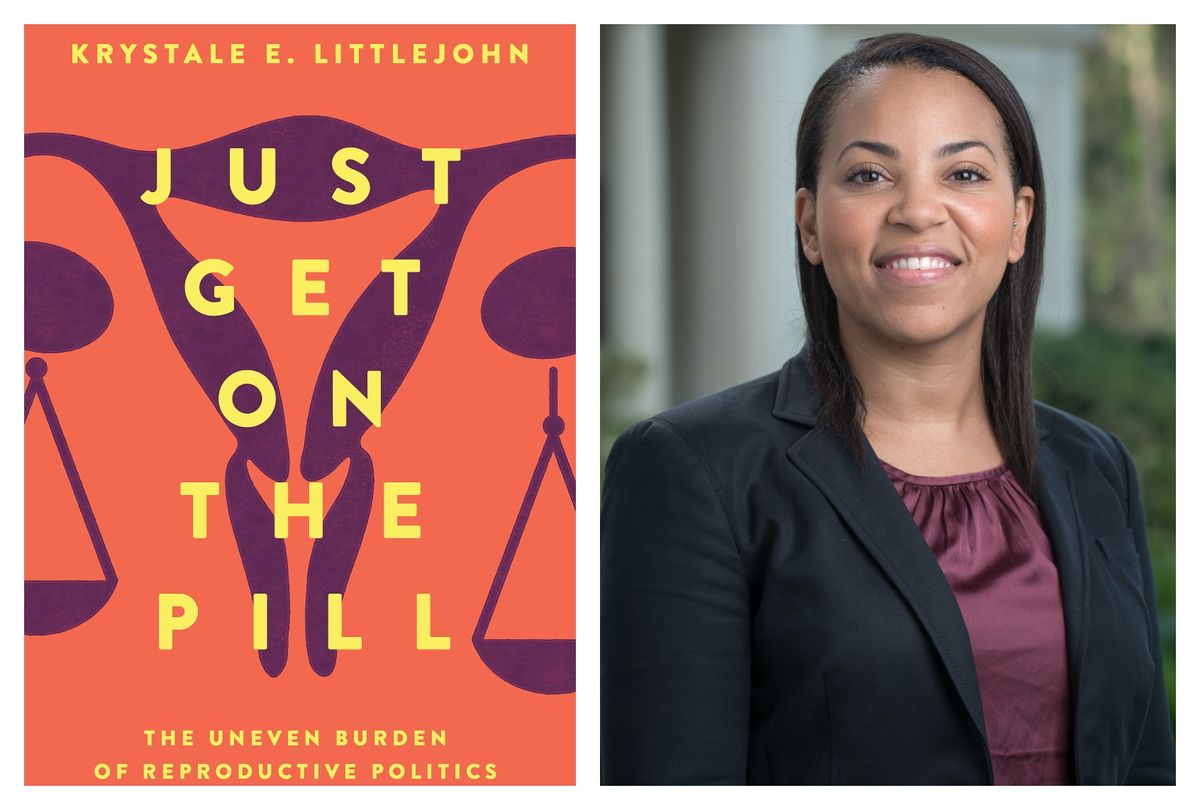

In University of Oregon professor Krystale Littlejohn's newly released book, "Just Get On the Pill," Littlejohn explores what she calls "the uneven burden of reproductive politics." This entails the cultural and societal pressures women face when they're told to "just get on the pill," or really any hormonal birth control method, and therefore assume sole responsibility for preventing pregnancy — no matter the cost to them.

Over the course of hundreds of interviews, originally part of a study with Stanford and UC Berkeley about why women don't always use birth control when they want to prevent pregnancy, Littlejohn recalls seeing universal threads in the diverse interviewees' stories. Parents, friends, doctors, and certainly, partners who all had their own convenient reasons for not wanting to use condoms, implicitly or explicitly pushed each of these women to get on birth control.

While Littlejohn notes that hormonal contraception can be a vital and empowering resource for those who freely choose it, based on different social contexts, it can also be a part of denying women agency, autonomy and even safety. Using long-term hormonal birth control methods can make women more susceptible to STDs if sexual partners use this as an excuse to not wear condoms, or even more susceptible to unintended pregnancy, if birth control is used inconsistently and without a condom.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Our public conversation around birth control has fixated for so long on a rights framework, for example, fighting just to get employers and insurers to cover contraceptives, Littlejohn notes in "Just Get On the Pill." Somewhere along the way, we forgot to ask people who use hormonal birth control whether they feel safe and supported in doing so, or whether the side effects they experience are manageable. And certainly, we forgot to engage in a collective conversation on condom etiquette and safety.

"The real message here is reproductive autonomy has to be at the center of our discussions and thinking about birth control and pregnancy prevention," Littlejohn told Salon. "People should absolutely have access to birth control so they have the freedom to manage fertility as they want to, and of course they should not be pressured to do so."

In an interview on her new book, Littlejohn discussed the surprising and upsetting revelations of hundreds of interviews with women about sex and birth control, the invisible gendered labor of managing birth control side effects, what sex-positive parents are and aren't getting right, and more.

At one point you cite a surprising statistic: 65% of women have never bought their own condoms. When did it first occur to you that we assign genders to condoms and birth control pills?

I want to say it was the third time reading the transcript — the team interviewed over 100 women, and it produced thousands of pages of transcripts. Over the course of several years, doing my analysis, I realized with bodies and birth control there's a really important phenomenon taking place that I just wasn't as trained to be as attuned to. I realized this is the story I want to tell — the ideas about bodies and gender that are fundamentally shaping how people behave around birth control, having these really negative consequences. So, I wish I could say, "I went in knowing this was important!" But instead, it only came up through reading the transcripts, having these interviews, and that's the power of sociology.

Many of the interviews seamlessly blend together. At what point did you start to see universal threads in these diverse women's experiences with compulsory birth control use?

I saw that pretty immediately, as I was reading over the transcripts and this came up over and over again. In terms of the interviews, for context on the structure, we asked women in the study to start with the first partner they had sexual intercourse with, and about every single partner after that, their experiences with pregnancy, birth control, abortion, orgasm. We tried to get as full of a history as we could, and what I noticed is how many people, partner after partner, would just not wear condoms, partners resisting condoms, telling them they should "just get on the pill," having parents telling them they should get on birth control, friends telling them to.

It just was this really pervasive phenomenon. I just remembered talking about it often, not just in my research but folks in my life, to tell them how frustrating their experiences were, and hear so many people in my circle just hear how much it resonated with them too.

Your book puts into words something so relatable to pregnant-capable people: that pregnancy prevention is a form of labor that, like a lot of domestic labor, falls on our shoulders. As you were conducting these interviews, is that an idea that resonated with a lot of women you interviewed?

They absolutely talked about frustrations with having to be the ones to prevent pregnancy, they talked about frustration with their partners not understanding how much work it was to prevent pregnancy. Whether that's trying to go to the clinic to get their birth control method, having to take it every day, dealing with side effects — there was a lot of frustration around this uneven burden they face.

And as I was writing this book, what came up is this is absolutely gendered, and public health has often encouraged cis women to get on birth control, but there are pressures folks face across the gender spectrum if they can get pregnant. [People of all genders] experience those pressures but also don't get their needs met, because we only talk about cis women and cis men, and it's also cis women who have to carry the burden.

So it was striking to see how many women and people felt frustrated with the uneven gender division of labor in their lives, and also disappointing how many partners were letting them down by not stepping up to take responsibility for preventing pregnancy, or pressuring them to use prescription birth control, or people taking off condoms when they'd agreed to use condoms. It was upsetting for me as a researcher who was learning about people's experiences, to see how much pain was involved, and the labor they had to do was intense and isn't given enough attention.

A few years ago, a study of male hormonal birth control pills was canceled when the male subjects started to experience side effects people who take "female" birth control pills often experience daily. How do you see this in relation to your book? Is weathering the side effects of birth control a form of labor we assign along gendered lines?

There is this expectation that women should have to put up with the side effects they experience if they want to prevent pregnancy, that's just what they're expected to do without a focus on what that means. And for many of the people I interviewed, when they experienced side effects, they stayed on their birth control. They didn't just stop their methods, although my research does show dissatisfaction is a big part of why many women do stop using birth control methods.

When we talk about the burdens of using methods and managing side effects, it's really important to highlight just how much effort and work goes into that. People talked about taking their pill at night so if they had nausea they didn't have to deal with it during the daytime. They talked about the different methods or strategies they might have to use to try and manage their emotional side effects when they had challenges with their emotions in relationships and at work. These side effects weren't trivial. People talked about feeling fundamentally affected, their self-esteem, relationships, ability to experience their sexuality in a way that felt freeing, if they had to deal with spotting all the time.

There's this gendered history of when women complain about things, they might be hysterical or overreacting. There are people out there who want to help people use birth control, but need to take seriously the complaints and challenges that they have using these methods. I believe in the power of birth control, and it's incredibly important to help people achieve their fertility and reproductive goals. But I also think it's important to think about what it means for them, how it affects their lives if they're not having the best experience, so we can understand how to support them.

Contrary to prevailing narratives, your book asserts everyone should have access to birth control, but taking it isn't inherently "empowering" based on the social contexts that push us to do so. Is it possible to challenge barriers to access contraception, and also openly discuss societal pressures to put women on birth control? What are some of the shortcomings in the conversation around birth control from our reproductive rights framework?

We have to highlight how important contraception is for people, but make sure we're always thinking about the conditions under which people are using those methods. If we think about this historically, contraceptives themselves are incredibly powerful, but we know they've been used in really coercive and horrific ways. When you have these practices that pressure people to use birth control methods, that is not reproductive freedom. It's the opposite of what these methods are supposed to be used for, to create the lives they want.

Reproductive rights and courts, like right now, have failed to give people access to rights, and often violated people's rights. We see this in Texas right now. Reproductive justice focuses on rights, health and justice, and gets us to recognize how courts have failed marginalized people, and how compulsory, forced sterilization laws were upheld by the Supreme Court. We always have to be thinking about justice, not just what is legal and what is a part of people's rights, but also what is a just outcome. Even as people have the right to access birth control in this country, it doesn't mean our approach to their experience is just.

Speaking of reproductive justice, race and birth control habits were a very interesting part of your book. How does your book subvert racist ideas that people of some races experience higher rates of unwanted pregnancy because of carelessness?

Racism can really get hidden in public health and social messaging around unintended pregnancy. There are racial differences in rates of unintended pregnancy, there are class differences in who is more likely. You end up with these messages that get explicitly communicated, where you have people saying Black women, Latinas, poor women are just being irresponsible. They're more likely to have unintended pregnancies because they just can't commit to using birth control regularly, or their communities are more open to having unintended pregnancies.

It's really important to consider their contexts, and the contexts in which people experience pregnancy prevention methods are rife with gender inequality. From that perspective, it's not just contraceptive mistakes, that marginalized women are just not using birth control or not thinking about their fertility goals. You find they're facing partners just like women of all backgrounds who can be resistant to wearing condoms. They have to make these choices around what to do about that, and it might seem like the only thing to do is just get on the pill in response to that. But the women in the study, especially Black women — many didn't believe they had to be on the pill. They wanted their partners to use condoms. They were very interested in protecting themselves from disease, so they didn't believe they had to "just get on the pill" to protect themselves from pregnancy, and didn't believe it just has to be their responsibility to prevent pregnancy.

So the book really challenges the ideas we have about what happens for Black women in particular and low-income women, when they experience an unwanted pregnancy. Rather than just thinking about lack of contraceptive use and individual women making individual decisions cast as careless, it's really important to think of the gendered context they live in, that are fundamentally shaping their experiences with partners who are refusing to use condoms. Our social approach says that's not a big deal because women should just be on the pill anyway, until you interrogate that assumption. Sometimes [not using the pill] leads to pregnancies that are undesired, but it doesn't mean they were behaving carelessly — it's a reflection of gender inequality.

Some interviewees recount partners agreeing to use a condom and then removing it. More recently, there's been a lot of conversation about how this is a form of sexual assault. The subjects who recount this happening to them don't seem to realize this — do you think the lacking public education about sexual health options can also contribute to making women unsafe?

The interviews were conducted between 2009 and 2011, before there was a more public discourse around partners removing condoms during sex without consent. And the vast majority of people in the study saw it as something that was just this annoying thing partners did, not something that was a form of sexual violence. I can only think of one woman in the study who explicitly called her partner out on that, and she told him she only wanted to have sex with him if he wore a condom, though he took the condom off without telling her. She only realized after.

When she called him out and said he had assaulted her, he just laughed it off. Literally. It's one of those things where the discourse for most women wasn't there for them to recognize this is a form of sexual violence. So, instead, they just saw it as annoyances. Even in those cases like the woman I just mentioned, she did recognize it as sexual violence, but her partner just rejected her right to bodily autonomy, and said he didn't assault her when he in fact did.

We could do a great deal of positive work if people could understand that nonconsensual condom removal is sexual violence, and partners shouldn't do it. When it happens, that's a violation, instead of treating it as just "boys being boys" and not being able to control themselves.

Some of your interviews were highly upsetting to read, including when an interviewee recalls how her partner called her a bitch for not wanting to go on birth control, or all the excuses male partners had for not wearing condoms, and not accepting responsibility for unwanted pregnancy. In conducting these interviews, was it ever just really, personally upsetting to hear these stories?

This is definitely the kind of project where I sometimes just needed to take a step away from the data because it was hard to hear about people having these nonconsensual sexual interactions, and with partners they really cared about. That was really heavy and hard to grapple with, as well as how their partners would dismiss their experiences, or laugh about assaulting somebody — those kinds of things were really hard.

I am a researcher and I've been doing this research for more than 10 years now, but I'm also a human, and reading about people's humanity being violated in really egregious ways, that we overlook or don't know are going on in society, was often heart-wrenching, especially that it's not something we talk about. That was the hardest part of this work — to see violence be normalized as this everyday experience. But it made it even more important that I told these stories, for other people with these experiences, highlighting that that's unjust.

There were some parents in your book with very progressive views of adolescent sexual activity, who were very supportive of getting their children birth control or abortions. Yet you also rightly point out that while this may have been well-meaning, it reinforces how we pin all responsibility for pregnancy prevention on women. What can parents who want to support sexually active teens do better?

As I was working on the book, it was striking how many parents might have believed they were doing the right thing by just getting their daughters to get on prescription birth control. But they were in fact making it harder for their daughters to protect themselves from disease, and pregnancy, because they could have been better suited for using condoms.

For parents who are trying to help their children have healthy sex lives, a key thing is to make sure their children are aware of all the birth control methods that are out there instead of gendering birth control and assuming that condoms have to be tied to a particular body. They also have a right to expect partners to use condoms. For parents trying to teach their boys and kids who can get others pregnant, teach them condoms are important to use and they should take responsibility for that rather than on their partners to do all the work to prevent pregnancy. They have a big role to play in doing so.

Changing the language around birth control, gendering condoms, calling them male and female condoms, is really counterproductive, and can seem trivial, but it's not. If someone is regularly referring to the condom as male, people will make associations about who that is for. So, using "internal" or "external" condom makes it so people of all genders can use condom, and there's no reason to assume a particular condom has to belong to a particular gender. We need to have conversations about what empowerment in sexuality looks like, what respect in sexual relationships look like, so people can know about their rights and safety in sexual interactions.

Shares