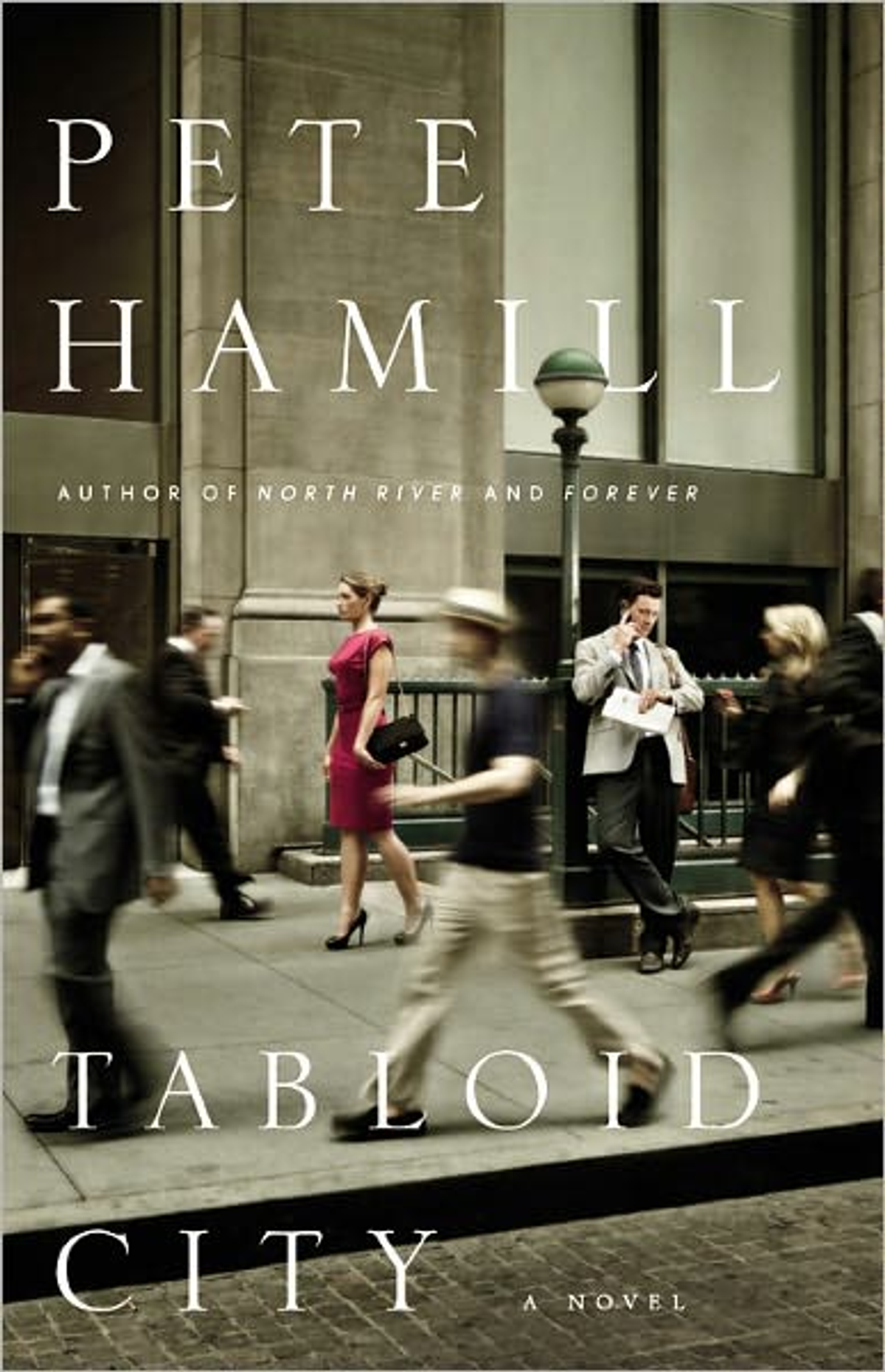

Pete Hamill has written many love letters to New York City, in fiction, journalism, and memoir. With his latest novel, he's written a nostalgic love letter to the New York City daily tabloids. "Tabloid City" shifts perspective among more than a dozen characters, but at its heart is Sam Briscoe, a 71-year-old editor who wears fedoras and trench coats and says "goddamned" a lot. Sam helms the New York World, Gotham's last afternoon tabloid, which, like all newspapers, is "under assault from digitalized artillery."

Tabloids thrive on what Briscoe calls "murder at a good address," and it is a Greenwich Village double homicide, of a socialite and her secretary, that drives the fast-paced but occasionally implausible action here. Cynthia Harding, a wealthy patron of the New York Public Library, is found stabbed to death in her townhouse along with her employee Mary Lou Watson. Harding is Briscoe's longtime companion; Watson's husband is an NYPD counter-terrorism officer who worries that their estranged son, Malik, a radical Muslim, is connected to the crime. The novel's action spans one day, and its dizzying number of characters includes an elderly artist, a Bernie Madoff-esque swindler, a Mexican cleaning lady, a disabled Iraq veteran, a bitter gossip blogger, and a young reporter. Most of them are connected in some way, and circumstances throw most of them together at the scene of the novel's terrorism-related climax.

In addition to being a thriller, however, the novel is a sentimental elegy for the "profane, laughing city room" of yore, thick with cigarette smoke and the sound of clacking typewriters. As Briscoe deals with the death of his beloved Cynthia, he also faces an ominous early-morning meeting with the World's despised young publisher, who is rumored to be shutting down the print version of the paper. Hamill's long journalistic career includes stints at the New York Post and the New York Daily News, where he served as editor-in-chief. In "Tabloid City," which is narrated in a clipped, journalistic voice, the author reveals the most affection for the noble and doomed newspaper employees. Briscoe and Helen Loomis, the two veterans of the World's newsroom, pine for the past, romanticizing even those elements we're presumably better off without. Briscoe makes a sneering reference to the fact that the members of the online staff probably don't smoke, while Loomis, forced to trudge outside for her hourly cigarette, longingly recalls the good old days with "the reporters cursing and laughing, making sexist remarks, and racist jokes."

But if much has changed, some things still remain: Hamill seems to suggest that hope lives in the talented rookie reporter Bobby Fonseca, who, after receiving his first press card from Briscoe, "wore it to bed for a month, like it was a dog tag." He's not a smoker, and he'll probably end up working for the paper's digital version, but he still has the soul of a newspaperman. Glancing at one of the subway system's ubiquitous "If you see something, say something" signs, he thinks, "Nah, if I see something, I write something. I'm a reporter, man."

Shares