James Gavin's book about Chet Baker, the jazz singer and trumpeter who first gained fame in the early fifties and who, only a few years later -- and for the rest of his life -- was better known as a heroin addict as unregenerate as any in the history of the music, was first published in 2002, fourteen years after Baker's death in Amsterdam, at fifty-eight, almost certainly by suicide; it has only now appeared in paperback. This long lag is hard to fathom. As evidenced most strikingly in the portraits of Baker in Geoff Dyer's 1995 "But Beautiful" and Dave Hickey's 1997 "Air Guitar," and in the response to Bruce Weber's 1988 documentary film "Let's Get Lost," released just after Baker's death, and screened in a restored version at the Cannes film festival only three years ago, there has always been a Chet Baker cult.

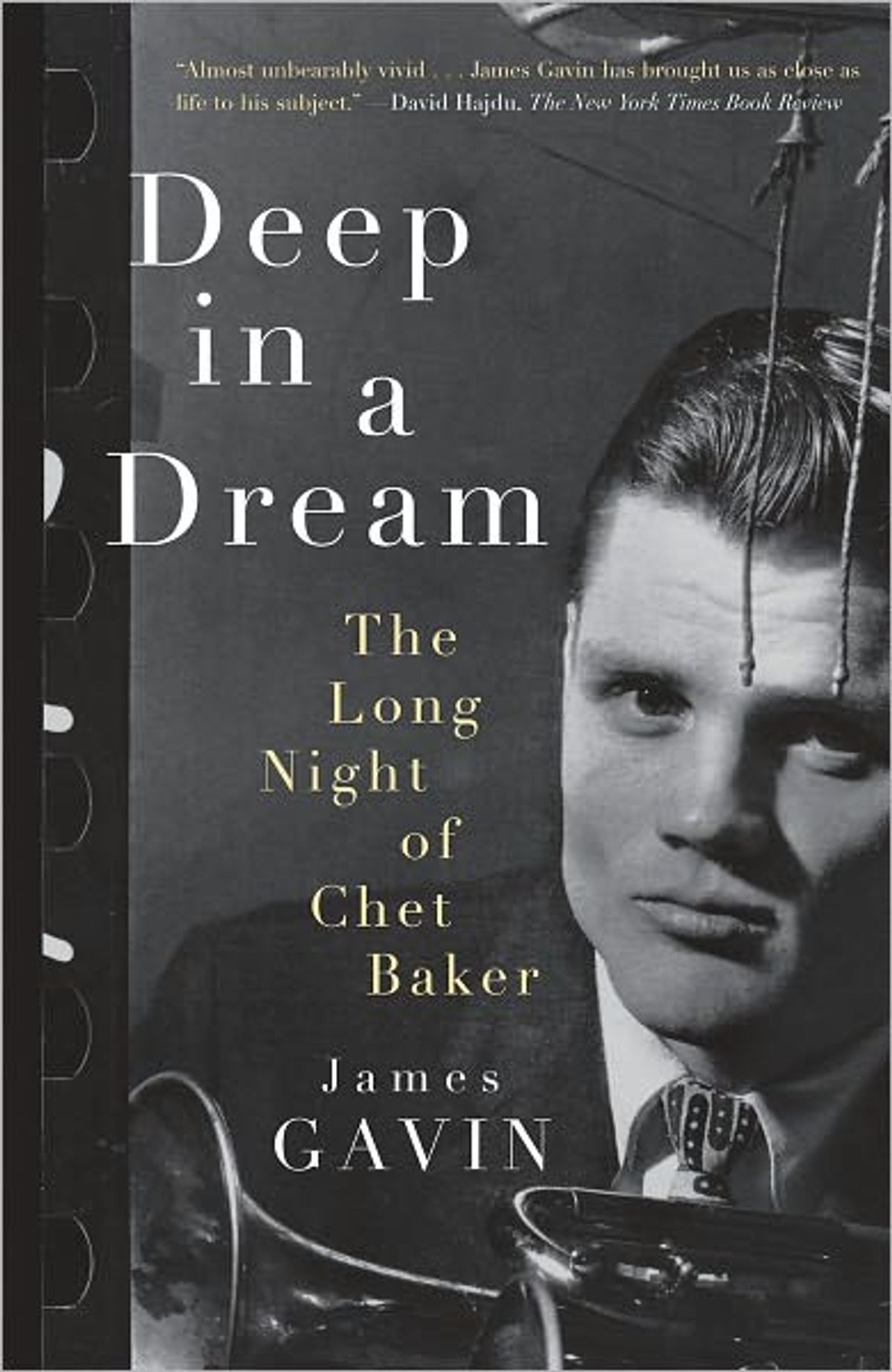

But more than that, "Deep in a Dream" -- named for a particularly affecting, cloudlike Baker recording from 1959 -- is not an ordinary biography, though there is nothing unusual about its form (from birth to death and aftermath) or style (direct and clear). It is a singular work of biographical art that makes most studies of, as Hickey's essay on Baker is so wonderfully titled, "A Life in the Arts," seem craven, compromised, or dishonest, with the writer falling back before the story he or she has chosen to tell, for whatever reasons offering excuses or blame in place of a frank embrace of the unresolved story each of us leaves behind, producing less any sort of real entry into the mysterious country of another person's life than a cover-up.

But more than that, "Deep in a Dream" -- named for a particularly affecting, cloudlike Baker recording from 1959 -- is not an ordinary biography, though there is nothing unusual about its form (from birth to death and aftermath) or style (direct and clear). It is a singular work of biographical art that makes most studies of, as Hickey's essay on Baker is so wonderfully titled, "A Life in the Arts," seem craven, compromised, or dishonest, with the writer falling back before the story he or she has chosen to tell, for whatever reasons offering excuses or blame in place of a frank embrace of the unresolved story each of us leaves behind, producing less any sort of real entry into the mysterious country of another person's life than a cover-up.

To put it another way: except in the rare cases of those strange creatures who, like T. E. Lawrence, create themselves to such a degree that it becomes nearly impossible to imagine that they ever experienced a trivial or even workaday moment, the dramatic sweep we find in novels or movies is not really the stuff of anyone's life. No matter how the writer may try to have it otherwise, most biographies are simply one thing after another. The life of a junkie is not just one thing after another, it is the same one thing after another -- and yet there is not a page in "Deep in a Dream" that is not engaging, alive, demanding a response from a reader whether that be a matter of horror or awe, making the reader almost complicit in whatever comes next, even when, with the story less that of a musician who used heroin to play than that of a junkie who played to get heroin, it seems certain that nothing can.

Born in Oklahoma in 1929, Chet Baker grew up in Los Angeles. He had a deep and instinctive ear for music, playing trumpet in high school, army, and junior college bands; in 1949, when he heard the Miles Davis 78s that would later be collected as "The Birth of the Cool," Baker "connected with that style so passionately that he felt he had found the light." That same year he was present at all-night sessions in L.A. to hear Charlie "Bird" Parker, and was shot up with heroin for the first time. He sat in with Dave Brubeck in San Francisco; in 1952 in L.A. he was called in with others to make up a group to back a wasted Parker.

That gave Baker an instant credibility in jazz. Ruined or not, Charlie Parker, with Dizzy Gillespie the progenitor of bebop, was the genius, the savant, the seer, the stumbling visionary who heard what others could not and could translate what he heard into a new language that others could immediately understand, even if they could never speak it themselves. If Parker said that Baker's playing was "pure and simple," that it reminded him of the Bix Beiderbecke records he heard growing up in Kansas City, that made the perhaps apocryphal story of Parker telling Gillespie and Davis, "There's a little white cat on the coast who's gonna eat you up" almost believable. But it was Baker's face -- as much or more than his joining in a new L.A. quartet with Gerry Mulligan, the baritone saxophonist and junkie who had played on the "Birth of the Cool" sessions, or Baker forming his own group and then headlining at Birdland in New York with Gillespie and Davis below him on the bill -- that made many people want to believe it.

Well before the end of his life, after he had lost most of his teeth in a drug-related beating in San Francisco, after he had turned into as charming, self-pitying, manipulative, professional a junkie as any in America or Europe, where for decades he made his living less as a musician than a legend, Baker wore the face of a lizard. In some photographs he barely looks human. But at the start he was, as so indelibly captured in William Claxton's famous photographs, not merely beautiful, not merely a California golden boy -- in the words of the television impresario and songwriter Steve Allen, someone who "started out as James Dean and ended up as Charles Manson." He was gorgeous, he seemed touched by an odd light, and he did not, even then, look altogether human -- but in a manner that was not repulsive but irresistibly alluring.

His legend -- the way in which, with the clarity and ease of his tone as a trumpeter, and the preternatural calm, quiet, and reflectiveness of his singing, the way in which he could, "somehow," as Gavin quotes the Italian pianist Enrico Pieranunzi, "express the question mark of life in so few notes," the way in which Baker was a cult in and of himself -- was as the years went on not just a Johnny Thunders death watch, a spectacle of self-destruction, the face of the monster slowly grinding down the memory of the angel. Rather it was, through all the years of working less as a musician than as his own pimp ("One uninspired night at the Subway Club in Cologne yielded three albums"), of a self-degradation so extreme it had to be, in its way, its own reward ("Waking from a nod ... he found his face crawling with cockroaches ..."), the chance that the pure talent, as a thing in itself, might still be there, might still emerge on any night, in any song, and then, again, vanish, humiliating the man who could not find his voice at will or even refused to, and mocking the memories of those who could not admit that they had not heard what they thought they heard.

Behind its own face, the legend was that of the solitary betraying his own talent, his own gift, and that solitary betrayal raising the specter of the smaller but no less real betrayals of anyone in any audience, one man standing for, and exposing, the self-betrayal of everyone else. "All this criticism," Gavin writes of Baker's crash in the then all-important jazz polls in 1959 -- after a phony cure at the federal facility at Lexington, in 1950s jazz lore almost as storied a place as any nightclub in Manhattan, after four months at Rikers,

implied Baker had let everyone down, dragging an American dream through the mud. 'Chet had the world at his feet in the fifties,' said John Burr, one of his later bassists. 'He consciously turned his back on it, and used drugs as a means of doing it. That's what he said about it.' Baker made no apologies. 'All the attempts to get him off heroin -- he didn't want to get off heroin,' said Gerry Mulligan. 'That, of course, is heresy in the modern world. You're supposed to be going, "Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa, oh God, help me." Chet didn't give a damn.'

In Gavin's hands this is a long, long story of infinite shadings, where every incident that is formally the same as every other nevertheless has its own color, tone, and sound. He never attempts to ingratiate himself into the story, to wrap himself in its putative hipness when Baker seemed the epitome of cool; he never preens in knowingness, or feigns intimacy with Baker when Baker is the epitome of everything desperate and sordid. He places hip words or drug language in quotes or follows them with explanatory parentheses ("His arms and legs were full of bloodied 'tracks'"), at once establishing his own distance from the story and refusing to allow the reader any false empathy or easy identification -- to strip the reader of his or her own putative hipness, the hipness of anyone cool enough to want to read a 400-page biography of Chet Baker.

Gavin seems to hold all of Baker's music, piece by piece, song by song, phrase by phrase, every show, every recording, in his head, all at once. He doesn't give the sense of merely knowing everything -- while some people in Baker's life, such as his mistress Ruth Young, plainly opened up to Gavin with extraordinary candor and perception, not everyone would speak with him -- but, through imagination as well as research, to have witnessed everything, even to have experienced everything. This is Gavin on Baker's first recording of "My Funny Valentine," by the sixties a jazz standard and "a pop cliché," but in 1952 a Rodgers and Hart obscurity, recommended, in the Mulligan group, by the bassist Carson Smith:

None of Smith's bandmates knew it, so he scrawled out the chords, then sang them the melody. Rodgers had stated a haunting theme in the first phrase, then explored it over and over, changing it subtly each time. The melody kept ascending, creating a tension that built to a soaring climax under the words "Stay, little valentine, stay!"

Mulligan and Smith threw a chart together that spotlighted Baker. Here the trumpeter had no clever arrangement to hide behind, so he played the tune as written, stretching out its slow, spare phrases until they seemed to ache. His hushed tone drew the ear; it suggested a door thrown open on some dark night of the soul, then pulled shut as the last note faded. Smith countered the rising melody with a descending line of quarter notes, ominous as a clock ticking in the dark. He ended by mistake in a minor key instead of the major one in the sheet music, giving the record one last chilling touch.

The song fascinated Baker. It captured all he aspired to as a musician, with its sophisticated probing of a beautiful theme and its gracefully linked phrases, adding up to a melodic statement that didn't waste a note. "Valentine" became his favorite song; rarely would he do a show without it, or fail to find something new in its thirty-five bars. At the same time, the Baker mystique -- a sense that "cool" was a lid on an explosive jar of emotions -- had its roots in that performance.

The description is so complete that when Gavin quotes Ruth Young on the 1956 album "Chet Baker Sings," with "My Funny Valentine" at the heart of it -- "None of these songs had any meaning for him, truly. He could have been singing Charmin commercials. He was coming from a musical place, and the words were mere notes to him..." -- the view of an essential emptiness behind the creation of beauty takes nothing away from it.

There is Gavin's ability to put the reader in a room -- sometimes a room so archetypal it seems less to have been constructed for any practical purpose than to have been called up by the American imagination, as when, for Baker's monthlong engagement at Birdland in 1954, Charlie Parker, "banned from the club that bore his name," would stand out front telling customers what a wonderful musician they were about to see, and how then -- like Hurstwood haunting Carrie's backstage door, only to be chased away to wander the streets of New York, "losing track of his thoughts, one after another, as a mind decayed is wont to do" -- Parker "would sneak behind the building, walk through a back alley lined with trash cans, and knock on a door that opened into the dressing room. Baker or Carson Smith would let him in, and he and Baker would play chess until showtime. Then Parker would sit alone, keeping the door ajar so he could hear the music."

In this book, heroin, as it takes over one musician after another, one scene, one city, one country (Gavin quotes the pianist René Urtreger estimating "that by the midfifties, 95 percent of the modern jazz players in France -- himself included -- were hooked"), is more than a plague, more than an endless horror movie, the reels running over and over, out of order, back to front ("It was like the Night of the Living Dead," one fan tells Gavin of a Baker show in Paris in 1955. "Dark suits, gray faced, stoned out of their minds. Everything seemed strange to me, unhealthy. They were playing the music of the dead"). By the end -- "Baker filled the syringe, then held it up. 'Bob, you could kill a bunch of cows with this,' he said. He plunged the needle into his scrotum." -- "The man was a walking corpse," the Rotterdam jazz hanger-on Bob Holland told Gavin. "He was living only for the stuff. Music was the last resort to get it" -- it's as if heroin itself has agency, and seeks out bodies to inhabit, colonize, and use up, not a substance but a parasitic form of life whose mission is to destroy its host, knowing that it can always leap to another. But the essential humanity of the host -- his or her actual reality as someone who planted a foot on the planet before he or she left it, to be forgotten along with almost everyone else -- is, in these pages, never reduced, whether it is that of Baker, or any of the musicians, friends, wives, or lovers trailing in his wake, those he knew and those he didn't (from one dealer's client list: "Bobby Darin, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Anita O'Day, Lenny Bruce, and the rock star Dion"), by 1981 "a growing trail of corpses."

In this book, like Baker's fans, listening to a radio broadcast from Hannover, Germany, on April 29, 1988, where Baker was to recreate his 1954 album "Chet Baker with Strings," only days before playing in the street in Rome for drug money, they are somehow all present in the audience as Baker played. "With every defense shattered," Gavin writes, "he lived the songs with a painful intensity. The concert peaked with an epic nine-minute performance of 'Valentine.' Baker opened it with a trumpet chorus backed by guitar only, a chillingly stark musical skeleton; from there, his hollow, otherworldly singing drifted on a cloud of strings." And then, less than two weeks later, in Amsterdam, he propped open the window of his third-story hotel room, and crawled out.

Shares