One of the first stories I found both true and terribly sad is a chapter that comes in the middle of P.L. Travers' "Mary Poppins," an interlude devoted to the infant twins, John and Barbara Banks, in their nursery. (Jane and Michael, the older and better-known Banks siblings, have gone off to a party.) The twins can understand the language of the sunlight, the wind and a cheeky starling who perches on the window sill, but they are horrified when the bird informs them that they will soon forget all of this. "There never was a human being that remembered after the age of one -- at the very latest -- except, of course, Her." (This "Great Exception," as the starling calls her, is Mary Poppins, of course.) "You'll hear all right," Mary Poppins tells John and Barbara, "but you won't understand."

This news makes the babies cry, which brings their mother bustling into the nursery; she blames the fuss on teething. When she tries to soothe John and Barbara by saying that everything will be all right after their teeth come in, they only cry harder. "It won't be all right, it will be all wrong," Barbara protests. "I don't want teeth!" screams John. But, of course, their mother can't understand them any better than she can understand the wind or the starling.

It's at age one that we acquire our first words. This story, which made me so melancholy as a girl, is, among other things, about the price we pay for language, for the ability to tell our mothers that it's not our teeth that are upsetting us but something else. It alludes to what we have given up to be understood by her and all the other adults, our lost brotherhood with the rest of creation. Words are what separate us from the animals, or as Travers would have it, from the elements themselves, from everything that can simply be without the scrim of consciousness intervening.

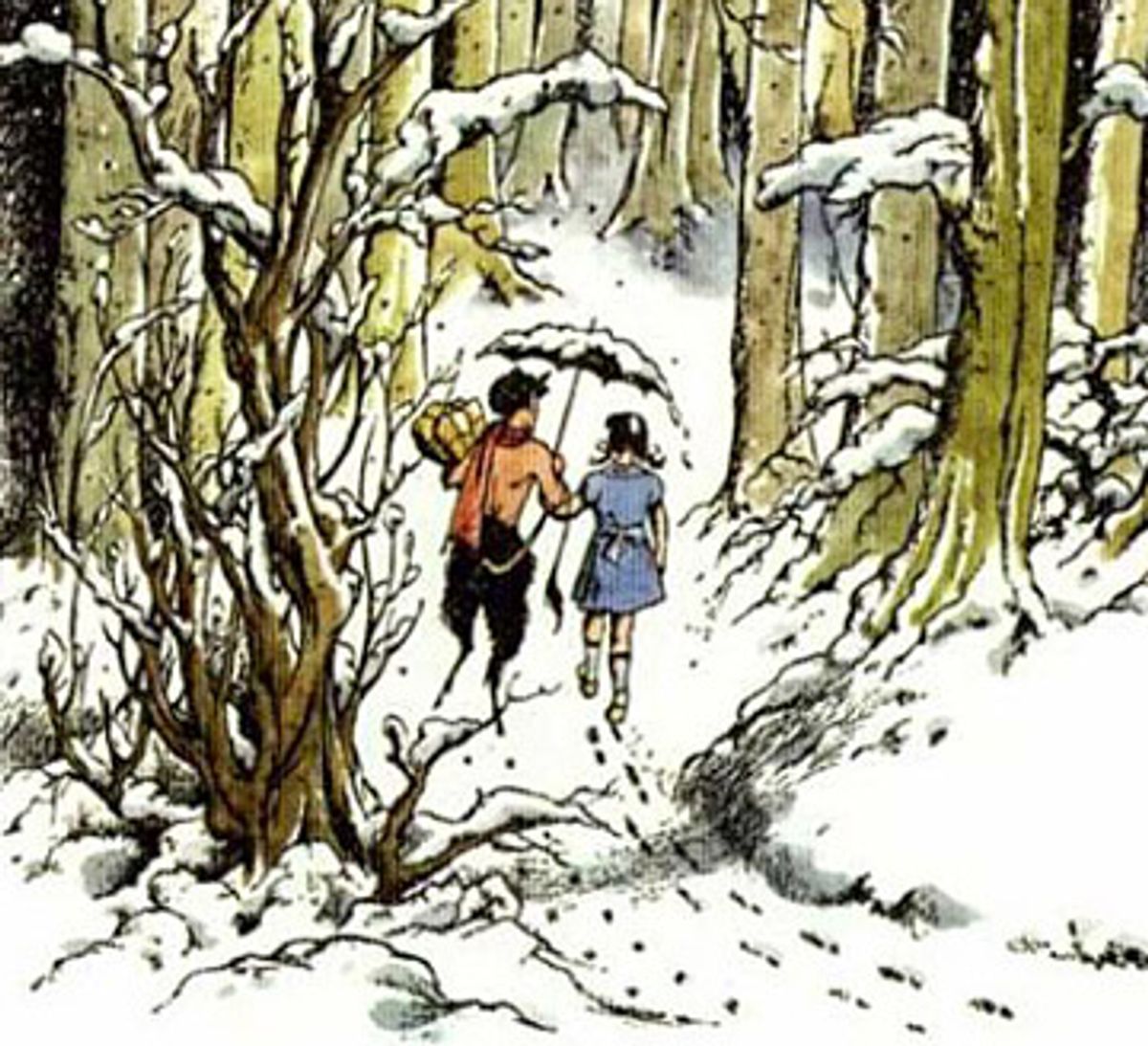

In C.S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia, this mournful rift is healed; there, people can talk to animals, to trees and sometimes even to rivers (as happens in "Prince Caspian"). People have longed to communicate with the universe since time immemorial -- a profound, mystical longing. Lewis' friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, described this as one of the two "primordial desires" behind fairy tales (after the desire to "survey the depths of space and time"): We want to "hold communion with other living things." But since children are literalists and materialists, not mystics, their love for animals, and for stories about people who can talk to animals, is seldom understood as a manifestation of this desire.

To say that, as a child, I -- and my brothers and sisters and most of our friends -- loved animals would be an understatement; much of the time we wanted to be animals. Take us to a park or some place with a rambling yard, and we'd immediately begin mapping out the territory for one of our elaborate games of make-believe. At first, we pretended to be various woodland fauna, inspired by the "Old Mother West Wind" books by Thornton Burgess, a series our mother read to us. At home, one of us would clamber up onto the roof of our ranch house (via the top bar of the swing set) to play the eagle who came swooping down to pounce on the squirrels and chipmunks below.

This preoccupation with animals starts early. Two friends of mine, twins named Corinne and Desmond, began pointing at themselves and saying "This is a puppy" almost as soon as they learned to talk. As time goes by and the impossibility of such imaginings becomes obvious, the ache for contact grows more desperate. By age seven, when I first read "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe," I longed for some better rapport with the family cats and the neighborhood dogs, with any kind of beast, really. Animals seemed like relatives left behind in the Old Country, except that the growing expanse that separated us wasn't a physical ocean but a cognitive one. They stood on the dock, getting ever smaller, while we children watched from the deck, on the way to a new, supposedly better way of being in the world, haunted by the image of what we were losing.

Animals, like infants, belong to the vast nation of those who communicate without words, through gesture, expression, scent, sound and touch. Children are immigrants from that nation, and like most recent immigrants still have a mental foothold on the abandoned shore. I believed, probably correctly, that I understood animals better and cared about them more than the adults around me. I could still faintly remember what it was to be like a beast, before language complicated things. But I didn't appreciate the inverse relationship between the individual self I was building out of the new words I acquired every day and the inarticulate world that moved away from me as my identity gained definition.

Watching Corinne and Desmond grow up, I have noticed another drawback to learning to talk: Speaking also ushers in the stage at which grown-ups stop doing anything you want just to make you stop crying. It's only when you can ask for something with words that people expect you to understand the word "no." So age one also marks the beginning of our entry into human society proper, where compromise is the price of admission. Many adults -- and especially the authors of great children's books -- view growing up as a kind of tragedy whose casualties include innocence and the capacity for whole-hearted make-believe. But kissing Puff the Magic Dragon good-bye happens later, on the brink of pre-pubescence. Travers, in her chapter on poor John and Barbara Banks, seems to be saying that even the smallest children have already suffered a heart-breaking separation, before they leave their cribs.

Words also introduce us to our most implacable enemy: time. Developmental psychologists believe that memory begins with the learning of language; to speak (or more accurately, to understand speech, since most children can comprehend before they can articulate) is to remember. With memory comes the capacity to dwell on the past and to anticipate the future; without memory, how could we know our lives and our selves? And without knowing these things, how could we own them? But as Travers' mournful little parable would have it, to speak is also to forget -- to forget what it is not to remember, to forget what it feels like to live the way animals do, in a perpetual now, unaware of death and outside of time.

Animals inhabit the world of raw experience we've left behind; animals are the people of our lost homeland. To a child, an animal seems like a compatriot. The attachments that I had to the animals I knew were every bit as powerful as my feelings toward, say, my siblings (and less ambivalent, too, since I wasn't competing with the family cats for my parents's attention or a bigger share of the french fries). It's true that some adults still feel this way about their pets, and if you ask them why, the explanation often has to do with the transparency of animals' affection, their sincerity, which also turns out to be connected to their lack of language. Animals can't speak, ergo, they can't lie.

Yet the most cherished creatures in children's fantasy are talking animals. If we have mixed feelings about the gifts of language and consciousness, we have no intention of surrendering them. Instead, we want to bring animals along with us, into the solitude of self- knowledge, perhaps hoping that they'll make it a less lonely place for us. Children are more likely than adults to fantasize about talking beasts because kids don't have the logical faculties to see that giving animals the power of speech would surely spoil everything we like about them.

Talking animals were one of the things I loved most about the Chronicles as a child, but over the years that aspect of the books has lost its old allure. Once I would have given anything to join the Pevensie siblings at the round dinner table in Mr. and Mrs. Beaver's snug little house, trading stories about Aslan and eating potatoes and freshly caught trout. What I now like about animals -- their lack of self-consciousness -- I know to be intimately bound up in their speechlessness. As a little girl, I suspected them of having inner lives much like my own, if only they could (or would) tell me about it; now, I recognize that their charm lies in their lack of such secret thoughts. If my neighbor's cat, my friend's dog, the squirrel who sometimes treks along my fire escape, peering in on me while I'm reading on my sofa, could speak, would they really have anything to say that they can't already communicate well enough in their usual way: by purring, snuffling, wagging, chittering?

Stories about talking animals are not, of course, solely the province of children's literature. Folklore -- which is made by and for adults -- has its share of them, too, but it always uses talking beasts didactically, to personify a particular principle or trait: the wily fox, the fearsome wolf, the methodical tortoise. The animals of fable and fairytale are used to signify an identity that is simple and unchanging. Take the scorpion who breaks his promise by stinging the frog who has agreed to carry him across a river; when asked how he could betray his rescuer, he replies, "It's my nature." People repeat this parable as a way of asserting that a thief is always a thief, and a liar is always a liar, so it's best not to trust either one.

Adults rarely tell each other real stories (as opposed to fables and parables) about animal characters because the adult notion of a good story -- especially now, a few hundred years into the history of the novel -- demands psychological change, enlightenment, growth. When a contemporary novel with animal characters appears -- Richard Adams' "Watership Down," for example -- even if in most ways it meets the criteria of adult fiction, its moorings there are never secure. Chances are it will drift, sooner or later, to the children's bookshelves.

Children freely and delightedly identify with the characters in animal stories, often more easily than they identify with child characters. Children's authors know that what insults an adult reader -- being likened to an animal -- delights a young one. Robert McCloskey's celebrated picture book, "Blueberries for Sal," for example, is simply an extended conceit on the similarities between the toddler Sal and Little Bear -- to the degree that at one point the two youngsters accidentally swap mothers. Curious George is ostensibly a mischievous monkey, but his most devoted readers recognize that he is also a wayward three-year-old.

And in Narnia, even God is an animal. Although as a girl I adored Aslan, the lion god Lewis invented to reign over the imaginary country of Narnia, he is another part of the Chronicles that no longer moves me as it once did. This is only partly because I now see, all too clearly, the proselytizing Christian symbolism, the theological strings and levers behind Lewis' stagecraft; the great lion seems less a character than a creaking device. I also stopped loving Aslan because I have since grown into the autonomy I was only tentatively experimenting with at seven. The kind of story in which a distant, parental presence hovers behind the scenes, ready to step in and save the day at the moment when hope seems lost -- a narrative safety net of sorts -- annoys rather than comforts me. I no longer need this in same way that I no longer need to hold someone's hand while crossing the street.

Still, being able to navigate traffic on your own doesn't keep you from wanting to hold somebody's hand every once in a while, if for different reasons. Holding hands feels nice, and this is one aspect of Aslan that has retained its charm for me. Unlike the God I was raised to worship, he is a god you can touch, and a god who asks to be touched physically in his darkest hour. In the darkest hour in "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe," he says to Lewis' two little girl characters, Lucy and Susan, "Lay your hands on my mane so that I can feel you there and let us walk like that." Later, the girls climb onto his "warm, golden back," bury their hands in his mane and go for a breathless cross-country ride through a Narnia you can almost taste, thanks to one of Lewis' most exhilarating descriptions:

"Have you ever had a gallop on a horse? Think of that; and then take away the heavy noise of the hoofs and the jingle of the bits and imagine instead the almost noiseless padding of the great paws. Then imagine instead of the black or gray or chestnut back of the horse the soft roughness of golden fur, and the mane flying back in the wind. And then imagine you are going about twice as fast as the fastest racehorse. But this is a mount that doesn't need to be guided and never grows tired. He rushes on and on, never missing his footing, never hesitating, threading his way with perfect skill between tree trunks, jumping over bush and briar and the smaller streams, wading the larger, swimming the largest of all. And you are riding not on a road nor in the park nor even on the downs, but right across Narnia, in spring, down solemn avenues of beech and across sunny glades of oak, through wild orchards of snow-white cherry trees, past roaring waterfalls and mossy rocks and echoing caverns, up windy slopes alight with gorse bushes, and across the shoulders of heathery mountains and along giddy ridges and down, down, down again into wild valleys and out into acres of blue flowers."

It is almost impossible to find the plain, untrammeled joy in being alive that Lewis captures in Lucy and Susan's "romp" with Aslan in the traditional Judeo-Christian canon. The scene is blissfully sensual. It ends with all three "rolled over together in a happy laughing heap of fur and arms and legs." It would be hard to imagine the two girls sharing the same intimacy with a god in the form of a man -- or, rather, it's imaginable, but only with uncomfortable undertones.

"Animal" is a word sometimes used as a synonym for "carnal," and not in a good way, but Lucy and Susan's desire to touch Aslan, and Aslan's desire to be touched by them is carnal without ambivalence because he is an actual animal. Like most adults of his time and place (or adults of most times and places, for that matter), Lewis had mixed feelings about sex, but in this scene, at least, he escapes into a pure delight in physicality that's almost, but not quite, erotic. And although I myself am ambivalent about having to use the word "pure" to characterize that delight or -- worse yet, the word "innocent," which I've so far managed to avoid -- there is no other adjective for it. Even if I would prefer not to think that sexuality contaminates experiences, I have to admit that ambivalence about sexuality does just that. Lucy and Susan's romp with Aslan is as much pleasure as you can have in a body without sex -- that is, without sex and the ambivalence that comes with it.

It's also transcendent. "Whether it was more like playing with a thunderstorm or playing with a kitten, Lucy could never make up her mind," Lewis writes. What Susan and Lucy are tumbling around with on Narnia's springy turf is something titanic and formidable, not just their own carnality with all its dormant, unpredictable potential, but a divinity who has just unleashed snowbound Narnia into the rampant vitality of spring. Yet if you're going to romp with a thunderstorm, what better form could it take than a gigantic kitten? Play and youth, too, are forces of nature.

When I read picture books to my toddler friends, Corinne and Desmond, they like to sidle up close to me. Their little fingers creep under my watchband and twine around my thumbs like the ivy that, under Aslan's direction in "Prince Caspian," pulls down all the man-made structures in Narnia. The twins can't sit still; they have to fiddle with locks of my hair, climb onto my shoulders and into my lap. I usually wind up with a foot in my solar plexus and a head blocking my view of the book I'm supposed to be reading. They make me feel like a patient old dog, beset by puppies, my ears chewed on and paws squashed. I suppose they'll only be able to get away with behaving like this for a few more years, when, inevitably, self-consciousness will set in. Except, of course, with animals, who have only ever had this way of showing their love.

Excerpted from "The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia" by permission from the author.

Shares