Once upon a time I was sure I knew why people like to read true-crime books -- those trashy, bizarre, splashy stories of real-life murder and mayhem. They liked comparing themselves to the villains, I thought, and patting themselves on the back for being so much better than the evil, dumb or deceived characters who populate true crime's dark, violent landscapes. There's nothing people like more than congratulating themselves on their own virtue and normalcy. I might have admitted that there was a soupgon of catharsis in it, too. Terror and pity: Now that's entertainment.

But I've grown philosophical in my middle age, and it seems to me now that there's far more to this genre than the simple opportunity to feel superior. The thing that all these books have in common is an exploration of the limits of human mastery. Murder is a power trip, proof of your ability to put an end to the existence of another person. What true crime shows us, in telling the stories of murderers and how they are brought to justice, is that human control is an illusion.

Money grants an extraordinary level of power to those who have it, and Thomas Capano had big money. The oldest son of a high-profile, immensely successful real estate development family in Wilmington, Del., he had been a state assistant attorney general, right-hand man to Wilmington's mayor and legal counsel to the governor. Worth a mere $5 million at the time of his arrest, Tom Capano was not the richest member of the Capano family. Brothers Louie, Joey and Gerry had continued the family business, enabling them to maintain vacation houses at the Jersey shore and a family condominium in Boca Raton, Fla. And in comparison with the du Ponts, whose sprawling local estates are called "chateau country," the millionaire brothers were small potatoes and nouveau riches; their father, Louis Sr., had been an immigrant Calabrese carpenter who made good. But new money or not, they had plenty of it.

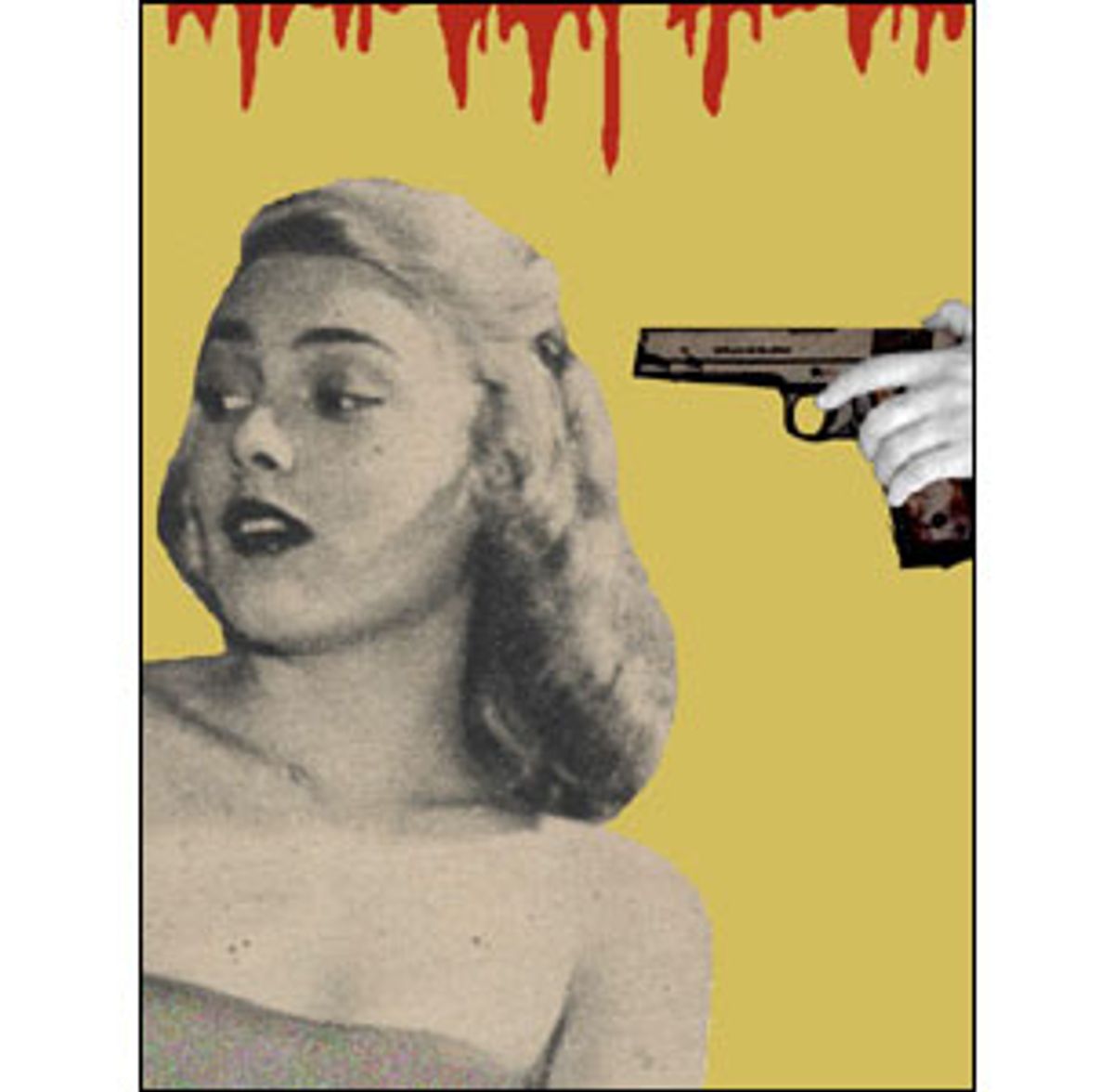

Added to Tom's dark good looks, his extensive education and his smooth charm, that money was more than enough to grant him nearly everything he desired, including women. Lots of women. Capano had almost 20 mistresses during his lengthy marriage, and at one point he was seeing at least three on different nights of the week. One was the gorgeous, exuberant and troubled Anne Marie Fahey, 30, scheduling secretary to Gov. Tom Carper. When Fahey disappeared on June 27, 1996, her diary revealed her secret life, and Capano instantly became the prime suspect in a jaw-dropping case of obsession, murder and betrayal.

Money figured prominently in the attraction Anne Marie Fahey felt toward Capano. Fahey, the youngest of six children, had experienced a chaotic childhood. When she was 9, her mother died, and her father descended into alcoholism and irresponsibility. During Anne Marie's teens, there were days when there was nothing to eat at home and the electricity and water were turned off. She took showers at school, did her homework by flashlight and sometimes moved in with friends of the family for weeks at a time. She fought with her drunken father, at first hiding from him under the dining room table when he became violent, but later threatening him with a field hockey stick when he stole her babysitting money. It was a rocky, humiliating existence, and Fahey never quite recovered from it.

In addition to his seductive wealth, Capano had a soothing, sympathetic personal style that invited confidences. Capano, 17 years Fahey's senior, appeared to be as much a father figure to her as he was a lover. "I've told him everything," she confessed to her diary. Fahey was accommodating, anxious to please and adept at disguising her pain. She was a compulsive neatnik -- "Anal Annie," some called her affectionately -- who even folded her dirty clothes in the laundry hamper and lined up stacks of coins with the heads all facing in the same direction. It was a way of gaining a semblance of mastery over her life, her psychiatrist later testified, as was her fierce battle with anorexia. Her body was beautiful, but for some reason she thought her breasts were "too big" and her legs were "too fat." In striving for perfection, especially as her guilty relationship with Capano developed and then deteriorated, she dieted toward a cadaverous ideal.

When she first met Capano in the spring of 1994, Anne Marie was a ravishing young woman: bosomy and curly-haired, with arresting blue eyes and rosy lips. Two years later, when Capano took her to the upscale La Panorama restaurant in Philadelphia for her last meal -- which she wouldn't eat -- she was barely a size 4, and her ribs showed whitely through her skin. Later that night Capano killed her with a bullet to the head and stuffed her frail body into a huge, 162-quart Igloo ice chest. There is little doubt that he had to break some of her bones to do it.

The question is, why? Most people, on first hearing the facts of the case, assume that Fahey, powerless and relatively poor, had threatened to expose Capano's infidelities to his wife and four daughters. Perhaps, they speculate, she was blackmailing him, and he killed her to shut her up. It's a common enough scenario, but in fact the situation was exactly the reverse. About a year after their affair began, Fahey started to fear Tom Capano, and she broke off their sexual relationship. She characterized him in her diary as a "controlling, manipulative, insecure, jealous maniac," and told a security guard at work that he was "stalking" her.

Capano had left his wife the previous autumn, just when Fahey had begun to date Michael Scanlan, a quiet, handsome and highly moral man her own age. Anne Marie thought she might marry Mike someday -- but only if Capano could be persuaded to stay quiet about their affair. To that end, she had maintained a friendly e-mail correspondence with Capano and occasionally agreed to dinner invitations. She had even allowed him to lend her money and buy her small gifts. But she would not resume their intimate relationship. Her anxiety about his obsessive behavior -- his phone calls and e-mails, his questioning of her friends, his constant driving past her apartment to see whose car was parked in her driveway -- caused her to increase her reliance on the only power she had left: a defiance of Capano's desire to feed her. She would go to dinner, but she would not eat.

Fahey's psychiatrist, Michelle Sullivan, testified at the trial that Fahey had been making progress in facing her problem with Capano. Sullivan theorized that the only reason Anne Marie agreed to go out to dinner with Capano that last night was to finally make a definitive break with him. But Capano had to have his own way. His needs were non-negotiable. If Anne Marie wanted to leave him for another man, if she could no longer be cajoled with gifts and wheedling or subdued with threats of exposure, she would have to die. As the trial would prove, his arrogance had developed into delusions of omnipotence; he assumed he could get away with murder.

How does a man who has always had everything he wanted, who has succeeded at everything all his life, who has the power to obtain virtually anything he desires by merely opening his checkbook -- how does such a man develop a murderous level of obsession with the one young woman out of 20 who eludes his grasp? We can understand how Capano developed the arrogance, his confidence in his own abilities and righteousness. His illusions about his inherent superiority are not surprising. But the disproportionate, killing rage -- where did that come from? A man so confident, rich, successful -- why didn't he just shrug his shoulders and move on to the next conquest?

No less than four current books attempt to tell the story of Capano's life, the murder he committed and how he was brought to justice over the course of two and a half years of investigation and trial. The facts that have emerged are presented competently -- and lurid facts they are -- but none of these authors is able to answer the question of the true source of Capano's capacity to kill. A story like this is a testament to our inability to even explain the origin of evil, much less control its manifestations.

Virtually everyone associated with Capano suffered, innocent and complicit alike. Testimony during the trial destroyed the personal reputations of Keith Brady, Delaware's assistant attorney general, and Deborah MacIntyre, a quiet, independently wealthy and highly respected private school administrator, who turned out to be another of Capano's secret mistresses. She had participated in a threesome with Capano and Brady, and once agreed to have sex with a casual date while Capano watched them from outside her living room window. MacIntyre bought the gun Capano used to kill Fahey, and her testimony was pivotal in proving that the murder was premeditated.

To prevent MacIntyre from testifying, Capano tried to persuade jailhouse pals to arrange a burglary of her house in order to prove to her that he could "get to" her, even from inside the prison lockdown unit where he was held without bail for months before his trial. He provided another inmate with an elaborate plan of MacIntyre's home, including the number for her burglar alarm, and a list of instructions detailing where to find valuables and MacIntyre's stashes of sex toys and pornographic videos. Drawing an arrow to the huge floor-to-ceiling mirror in her bedroom, where he and MacIntyre liked to watch themselves having sex, he wrote that it "must be shattered" by the burglars: "ABSOLUTELY REQUIRED." Meanwhile he was writing MacIntyre melodramatic, manipulative and self-pitying love letters, which included his fantasies of her having sex with other men, "down on all fours, taking it doggy style." At the same time, in chatty letters to yet another mistress, he criticized MacIntyre's appearance and contemplated destroying her credibility by telling the court that she "swallowed and loved it."

Capano, supremely confident of his own ability to charm and manipulate the jury, eventually took the stand himself -- in defiance of his own million-dollar defense team's advice. In a bizarre, last-ditch attempt to deflect the weight of the evidence, he blamed the murder on MacIntyre, but the tale he told was riddled with absurd inconsistencies and improbabilities. Most say his arrogant insistence on testifying was the act that sealed his fate.

While he was in prison awaiting trial, Capano also tried to put out a murder contract on both MacIntyre and his own brother, Gerry. Gerry was forced by a federal narcotics sting to turn state's evidence, and in his testimony he detailed how he and Tom dumped Anne Marie's body from the deck of Gerry's fishing boat. Brian Karem's businesslike and thorough "Above the Law" opens with Gerry emerging from his home at 6 in the morning, hung over as usual and bewildered to find Tom sitting in front of the house in his Jeep Cherokee, reading the sports page. Powering down the car window, Tom said without preamble, "I need to use your boat." As Gerry later told the court, he knew immediately what that meant: Tom had an inconvenient corpse on his hands.

Tom, apparently contemplating Fahey's murder months earlier, had told Gerry that he was being extorted by a mysterious woman who was threatening his children, and that he might have to kill the blackmailer someday. If he did, Tom said, could he use Gerry's boat to get rid of the body? Gerry -- not believing for a moment that Tom was seriously considering killing someone -- had agreed. That morning in June 1996, when Tom called in his promise, Gerry was stunned and fearful; he initially refused to get involved, but Tom somehow convinced him that "nothing would happen."

"Above the Law" follows as the two men load Anne Marie's makeshift coffin onto Gerry's boat and head out to sea, stopping some 60 miles out, in the 200-foot-

George Anastasia, veteran reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, opens his account, "The Summer Wind" (which was the name of Gerry's boat), with the most critical fact of the entire case: When the two brothers heaved the huge cooler overboard, it wouldn't sink. Gerry grabbed the shotgun he kept on board for killing sharks and fired a deer slug through the side of the cooler, causing a reddish fluid to gush out into the sea -- Anne Marie's blood combined with the melted ice Tom Capano had packed around her. Still the cooler wouldn't sink. Unnerved, Gerry pulled alongside, handed his brother the boat's anchor, and turned his back, retreating to the bow of the boat. Capano tied the anchor to Anne Marie's body and dumped her out of the ice chest. Gerry turned around just in time to see one slim foot disappearing into the deep.

Anastasia takes a novelistic view of the case, frequently re-creating conversations and thoughts, and he paints his scenes well. His is an economical and elegant account of the whole "surreal" story, which he calls "more 'Jerry Springer' than jurisprudence." On the question of why Capano murdered Fahey he seems to blame society as much as the people involved. The case, he says, with its gleefully publicized details and its egoistic, unrepentant central character, is emblematic of American tabloid values at the end of the millennium, "when all vestiges of public shame seem to have faded away."

Cris Barrish and Peter Meyer's "Fatal Embrace" begins with the discovery of the discarded cooler by a local fisherman, an event so improbable and so essential to making the case against Capano that the lead prosecutor, devout Catholic Colm Connolly, did not hesitate to imply that it had been the result of divine intervention. With the cooler in hand, it was impossible for Capano's defense team to contend that Gerry had fabricated his story of the disposal of the body. Barrish and Meyer's effort suffers from a common problem in collaborations, an unevenness of voice. They sometimes veer with breathtaking speed from breezy and staccato interior monologues to weighty, "artistic" descriptions.

Ann Rule, a former policewoman now known as "The Queen of True Crime," takes us on some lengthy (and sometimes yawn-inducing) journeys into the past in "And Never Let Her Go." This is the version that makes the most extensive effort to explain the complicated relationships Fahey and MacIntyre had with Capano. It is rife with psychological analysis, much of it convincing but some painfully awkward. Rule's defense of Fahey involves dismissing the remotest possibility that Anne Marie was conflicted about her rejection of Capano. Fahey, it seems, must not be accused of encouraging Capano's continued interest in any way. As a result, Rule speeds quickly past evidence that Anne Marie felt a little jealous of Capano when he took other women to dinner, and Rule tries to make us believe that it is insignificant that Anne Marie phoned Capano -- and not her new boyfriend -- to come and get her when she fainted from self-imposed hunger at work a few weeks before her death.

Rule obviously had the best access to Debby MacIntyre, and she is careful to paint a picture of her as a woman blindly in love and consequently a helpless pawn in Capano's hands. MacIntyre supposedly didn't even enjoy the sexual escapades she revealed at the trial, but went along with them because she was afraid that Tom would leave her if she didn't. Undoubtedly the prosecution understood that it was important to establish this point for the jury, because if Debby had relished her romps, the jury might label her a "bad" woman, and by extension an unreliable witness. But is it necessary to maintain MacIntyre's pretense of total purity in the "true story"? In spite of these pungent whiffs of feminist victim mentality, there is much that rings true in Rule's reconstruction of the women's states of mind. Yet even she cannot convincingly plumb the psyche of Tom Capano.

Like most true-crime stories, the Capano murder books remind us how fundamentally unmanageable humanity's darker impulses can be. We may begin them thinking that if we can explain murderers to ourselves as understandable products of observable forces, then we can encompass them mentally, and more easily dismiss the possibility that our friends and neighbors -- or we ourselves -- may be capable of such crimes. But what are we to make of a suave, universally respected attorney, the product of an apparently happy childhood, a rich, admired, sexually satisfied, politically influential man, whose obsession with control leads him to kill -- with no apparent remorse -- a woman he supposedly loves? Capano is an affront to our preference for an explicable, predictable world.

Capano sits today on "max max," Delaware's Death Row. His bare 10-foot-square cell, where he dines on baloney sandwiches and is limited to one phone call a week, must be a special circle of hell for a man who used to savor the best life could offer. He will never touch a woman again. The man who had to be the master of everything and everyone is himself at the mercy of the state, which will eventually express its ultimate power in the way Capano indulged his own over Anne Marie: by ending his life.

It's justice, and justice is all we have. But justice, too, is another of our illusions of control. We may be able to put an end to the uncomfortable fact of Tom Capano, and even feel smugly satisfied that he will incur the spiritual judgment he deserves. But inexplicable evil will continue to exist -- and Anne Marie Fahey will still be dead.

Shares