Last spring, shortly after I published my first novel, I met a very famous author who referred dismissively to a fiction writer's first work as autobiographical throat-clearing. "You must get beyond it and get over yourself to find your true work," he told me. "Even first published fiction that has great artistic merit is only valuable to its author as a stepping stone in her creative life."

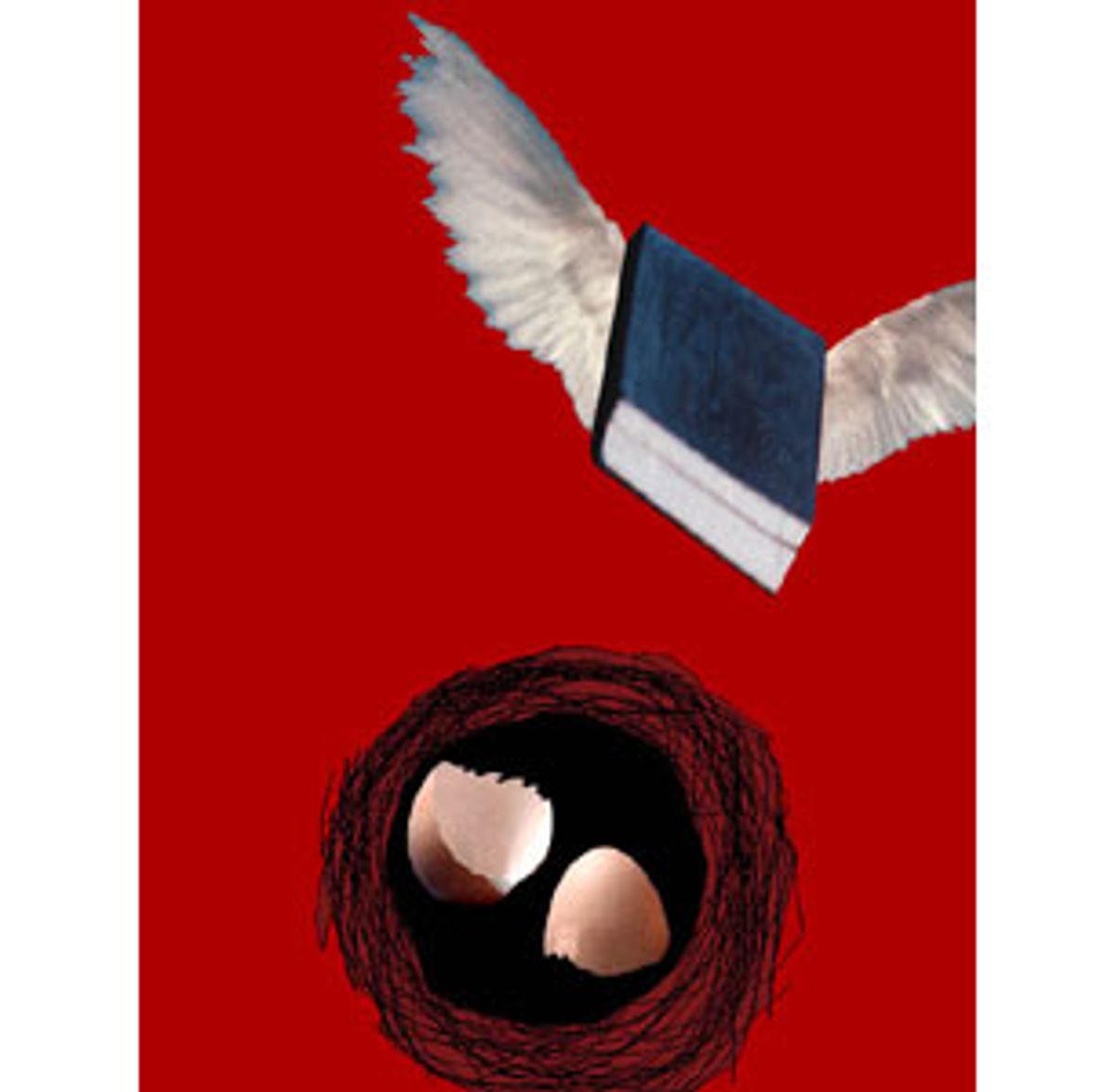

Seeing your first publication is supposed to give you a vantage on a career, on how to construct a lifelong project of a body of work. But, as I had just learned from my own initiation, many writers experience their first publication as a profound letdown that obscures many of the original reasons they wanted to write. Some authors whose first work is greeted with great excitement (or lack thereof) find that it permanently freaks them into silence or worse (much worse), mediocrity.

"There is an expectation now that the writer's first effort must be their best or at least spectacular, that you must cash in while you can, and that the whole culture is rooting against you when you're established in your career," says Newsweek book critic David Gates, the author of two highly acclaimed novels and the recently published short story collection, "The Wonders of the Invisible World." "Many of the [current] literary biographies tell the story of early promise and some success and then the long slide down, and now writers dread acting it out."

Lan Samantha Chang, author of the award-winning short story collection "Hunger," was so wary of the phenomenon Gates describes that, she says, "I delayed showing anyone my work for five years from when I could've. I wanted to be old enough to be certain of my artistic vision, to be able to withstand whatever happened when my first book came out."

What is it about the publication process that can be so disorienting? "Shortly after my book came out I realized that my relationship to my writing had changed forever," says Jhumpa Lahiri, author of the widely praised story collection "The Interpreter of Maladies," whose work was selected for the New Yorker's 20 under 40 summer fiction issue. "There were so many people attached to getting my book established in the world, so many new people who were in my life. All of a sudden my writing acquired a [new] seriousness ... I started feeling that all of those eccentric, hibernating writers made sense. They weren't weird anymore."

Yet, if by definition an artist wants to communicate with an audience, shouldn't getting her work out there be thrilling, especially for a first-time writer who's been dreaming about being published for years (if not most of her life)? Not necessarily: Even when the world responds in a good way, the noise can threaten to creep into a writer's head and silence her talent. This is famously the case with writers like Thomas Pynchon and J.D. Salinger -- the latter told Joyce Maynard that he left New York because he couldn't stand going to one more cocktail party and having someone come up and tell him about his characters.

For some writers, the rigors of publishing a first book harden their resolve. The late Robert Bingham, author of the edgy short story collection "Pure Slaughter Value" and the forthcoming novel "Lightning on the Sun," said, "One of the darker experiences of my book tour was walking into the Cambridge Barnes & Noble with my friend Ed Hemingway [Ernest's grandson] and being greeted by a sea of empty gray folding chairs, with only two people sitting up at the front waiting for me to read ... It was an image of complete horror."

Bingham used the mixed reception his first book received to fuel his artistic and career ambitions: "Some of the negative reviews of my book that I took to heart, that hurt, [said] that my characters were unsympathetic ... I didn't necessarily feel that this criticism was unfounded. Ultimately, I used the criticism ... But when I sat down to write my next book, I didn't think about the marketplace. I thought about my heroes in literature, Graham Greene and Robert Stone ... and I had their rhythms in my head."

When Ernest Hemingway published his first novel, "The Sun Also Rises," the New York Times gave it a two-line mention. According to Hemingway biographer Michael Reynolds, the book's publication provoked barely a ripple in the literary pond; the future god-king of American letters was merely promoted from a pool of authors publishing in small literary journals to the slightly more exclusive someone-worth-watching category. On the other hand, F. Scott Fitzgerald's first book, "This Side of Paradise," made a huge splash critically and commercially, transforming him into a celebrity "overnight." Which proves exactly nothing.

Success or no, once your first book is published you are forced to confront, head on, the reality of what you've decided to do with your life. You get an up-close look at the world of turn-of-the-millennium publishing, with all its grim, market-driven pragmatism -- the genteel, gin-soaked, word-loving world of Max Perkins and Edmund "Bunny" Wilson is long gone. "The literary culture has gotten tied up with the rest of the entertainment culture," says Newsweek's Gates. "Which is why there's such an emphasis on young and gorgeous writers."

And so, as a freshly published writer, you find yourself contemplating such things as the mega-advances you will never get; the inscrutable decisions by big book-selling chains that so profoundly influence your publisher's feelings about your book; the hideous "sales rankings" on Amazon.com; and perhaps most dishearteningly, the fact that, as Gore Vidal has pointed out, American fiction long ago stopped playing a vital role in our TV-saturated culture.

So, are you in or out? And if you decide that you don't care how your book is received, that from now on you're going to be like Emily Dickinson in her attic -- and to hell with all those horrible publicists! -- a nagging fear develops in the corner of your mind. If you don't care about your book's reception in the world, is that a first step in the direction of not caring about your book? Exactly why is it that you're spilling your life's blood to write if no one's going to read it?

Aspiring writers who haven't yet published a book often worry that, as Gates puts it, "somehow you're delusional, that you're not really a writer" -- but when your career exists mostly in the realm of fantasy, at least you have control. In your head you could be anyone, enjoying any kind of literary success, and because you don't suspect that there are people waiting for you to fall on your face, you have the self-granted freedom to write your heart out. The aging Hemingway fetishized his early, hungry days in Paris in "A Moveable Feast," yearning for the time when he was broke and unknown and the writing came easy: "I worked better than I had ever done. In those days you did not really need anything, not even the rabbit's foot, but it was good to keep it in your pocket."

The newly published writer usually develops a stinging self-consciousness that may make her keenly identify with Adam just after the first bite of the apple -- there's no way to fake innocence. You can never write again without the understanding of what's in store for your manuscript when you finish it. The world will make terrifying judgments about your talent and your vision, praise or dismiss your efforts or, perhaps worst of all, completely ignore them. Even a brave-hearted writer can feel, in these dark moments, a doubt or two about whether she has something worth showing this planet-sized jury.

The first-time author who's been turned into a "hot" commodity can feel stifled and set up to fail rather than encouraged by the attention. Danzy Senna, who wrote the critically acclaimed, bestselling novel "Caucasia," has recently completed a first draft of a second novel. She says that it wasn't easy to feel comfortable writing again, and describes experiencing a sense of immense, stultifying pressure at the critical enthusiasm that greeted her first book. "I felt, 'I'll never be able to live up to this accidental success,' and it really did feel accidental because I wrote ["Caucasia"] in graduate school -- it was a very private thing," she says. "I'm wary of being seduced by the publishing industry. I feel like I'm still learning to write, I'm still developing as writer ... It's so hard to be positioned in a place where you're really not ready for it."

No matter if publishing that first book is a good, bad or indifferent experience, it tends to jolt a writer's infamously delicate internal landscape. You will never be the same writer again. Whether you first publish at 24 or 44, you come of age when those bound galley proofs arrive in the mail. Like it or not, you must learn to reckon with your writing, and therefore yourself, as a marketable product. "There cannot be more than a handful of great or very good writers at any one time," Gates points out. "And that's exceptionally cruel because we all see ourselves as the leading actor in the drama ... We all want to be T.S. Eliot and not Conrad Aiken, Auden and not Isherwood."

Just lately I have realized what my next novel is about -- not the external plot, which I have known for a while but the real heart of the matter. I've been walking around like a newly pregnant woman, giddy and nauseated. Now, all I need to do is keep my head on straight while I get the first draft down. Funnily enough, I'm just as exhilarated, terrified and insecure as I was the last time around. And for that I'm grateful.

Shares