As a child, I was never a fan of anything. I didn't write letters to the Bay City Rollers. I was never a Trekkie or a Deadhead or a collector of Shaun Cassidy posters. But since that morning a couple years ago when, after reading P.G. Wodehouse's "Jeeves and the Tie That Binds," I first logged onto alt.fan.wodehouse (AFW), I've been hooked. As Bertie Wooster, "the master's" most effervescent creation, might say, "the L. has dawned, what?" I am a fan.

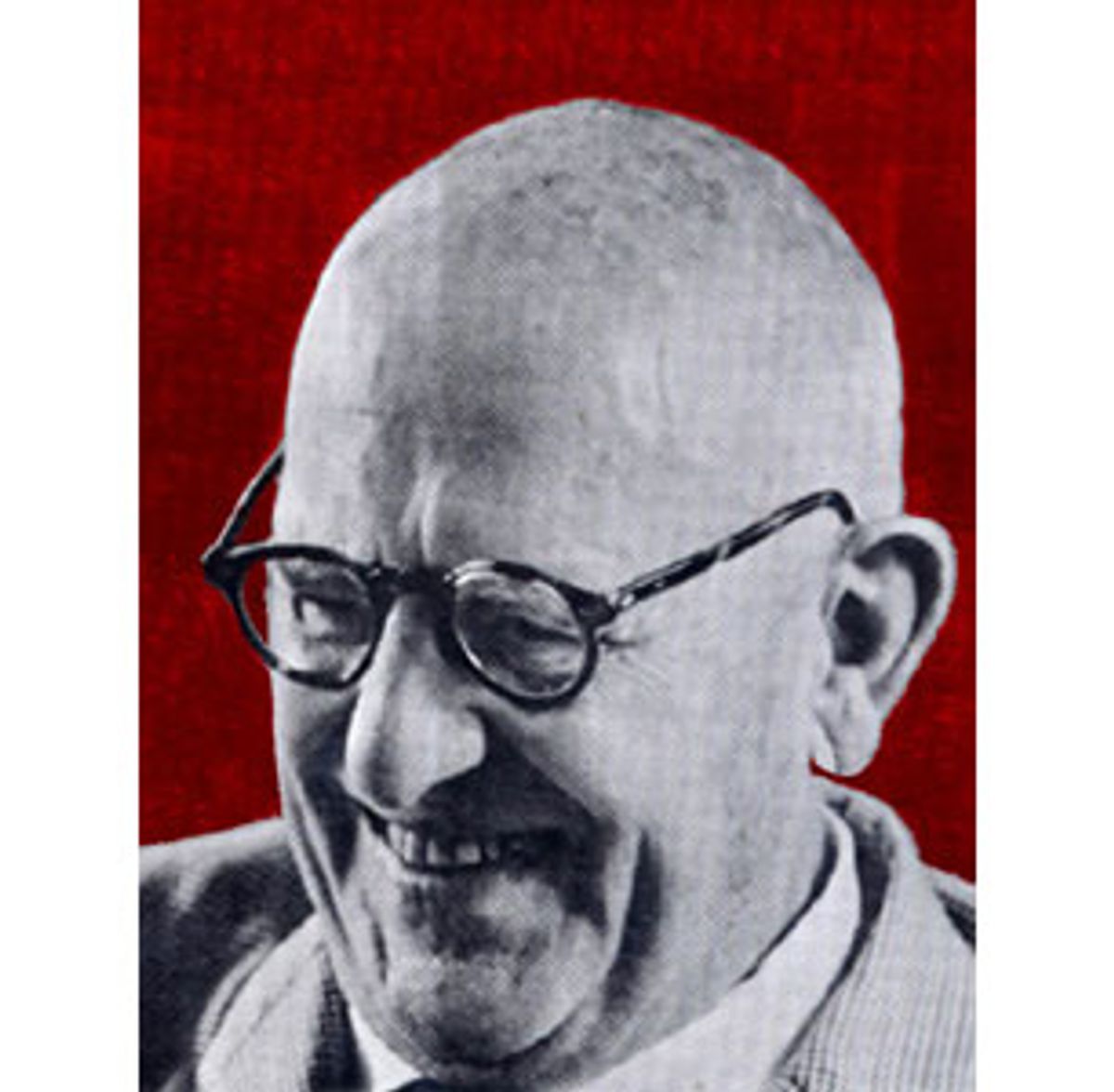

Pronounce him "Woodhouse," thank you kindly. He is a humorist without peer. In 92 books (including 11 novels and countless short stories about the inimitable valet Jeeves), not to mention musical comedies galore, his verbal pyrotechnics made me appreciate the possibilities of language long before I ever considered going to graduate school for English literature. At the core of his appeal is the Wodehousean prose style: a mixture of mangled literary references, Edwardian slang, invented slang, ludicrous formality and remarkable joie de vivre.

Here is Bertie on the subject of his friend Boko's troubled love affair:

Love's silken bonds are not broken just because the female half of the sketch takes umbrage at the loony behavior of the male partner and slips it across him in a series of impassioned speeches. However devoutly a girl may worship the man of her choice, there always comes a time when she feels an irresistible urge to haul off and let him have it in the neck. I suppose if the young lovers I've known in my time were placed end to end ... they would reach half-way down Piccadilly. And I couldn't think of a single dashed one who hadn't been through what Boko had been through to-night.

The ecstatic, cooing sort of mirth such passages invoke in me is certainly well and good. I'm all for it. But truth be told, the books are not really the point. What I really love is the newsgroup.

AFW is a mix of role-playing, hobbyism and scholarly inquiry. Whereas newsgroups devoted to canonical authors like Joyce or Kafka tend to maintain an intellectual focus, AFW recreates Blandings Castle, the setting for 10 Wodehouse novels and several short stories. Enter the online community, and you arrive at the Shropshire seat of the dotty Lord Emsworth, his faithful butler Beach and his prize-winning pig. Gone are the trials and tribulations of modern life: On AFW, we concern ourselves with acquiring the recipe for Jeeves' famous hangover cure, musing upon the meaning of "boomps-a-daisy" (something like "very well, indeed") and placing virtual bets on whether Boko Fittleworth's forthcoming infant progeny will look more like Winston Churchill -- or a squashed prune.

How do you pronounce "Featherstoneaugh"? The answer is "Fanshaw." We mire ourselves in Wodehouse trivia, along with bibliography, dramatic adaptations of various sorts and musical theater. Since I logged on to AFW, members have also conducted a pumpkin-growing contest online, polled one another to determine favorite cocktails and puddings and written a large collection of clerihews, most of questionable merit. Together, by submitting numerous nominations via the Web, we briefly managed to put "Only a Factory Girl" -- a bestseller written by the entirely fictional novelist Rosie M. Banks, who appears in several Wodehouse stories -- on Random House's controversial list of the 100 best novels ever written. It wasn't long, however, before the official chappies caught on, and Banks was replaced by Tolkien.

Each member has a "nom de Plum" (Plum was Pelham Grenville Wodehouse's nickname), and behaves accordingly -- breaking character often, but always infusing every exchange with Plum's signature verbal style. I love playing my part, immersing myself in this fictional world. It's different from the experience of reading a book, both because I become a participant in the fiction-making process rather than a passive reader, and because the fantasy is collaborative rather than experienced in isolation. We are all in it together. "What Ho!" I cry to Beach the Butler, who chose his nom because "there is a certain similarity in build: like Beach I am not fat, but far from svelte. I also have rather a fruity English accent ... And I wanted to be in Blandings, or 'heaven' as I tend to think of it." He is likely to respond with typical portly gravity that he trusts my weekend was satisfactory, Madam, and would I care for a cocktail?

The role-playing began in November 1994, according to longtime member Gussie Fink-Nottle, newt fancier and Drones Club member. "Aunt Diana (then writing as Stiffy) and I started a little in-character cross talk about the proper way to nab [policemen's] helmets," Gussie writes. (Pinching helmets is a popular sport of Wodehousean heroes when inebriated.) "That was a grand time indeed. There were ferrets about the place ... newts got painted orange and thrown into moats, people got potted, darning needles were bought [for puncturing the hot-water bottles of unsuspecting persons] ... in fact, everything that could happen in a PGW story happened."

All that was before my time. It was only about three years ago that I became Lotus Blossom, the impetuous redheaded American film star. "On the screen she seemed a wistful, pathetic little thing," wrote Plum in 1935's "The Luck of the Bodkins," "while off it 'dynamic' was more the word. In private life, Lottie Blossom tended to substitute for wistfulness and pathos a sort of Passed for Adults Only joviality which expressed itself outwardly in a brilliant and challenging smile and inwardly and spiritually in her practice of keeping alligators in wicker-work baskets and asking unsuspecting strangers to lift the lid."

Lottie maintains, in fact, that she has learned virtually all she knows about registering emotion on film by watching people's faces as they first encounter her pet. In my online incarnation, then, I let my alligator loose on occasion (Beach the Butler, if memory serves, had a nasty encounter with him, and the Dog MacIntosh was in serious danger). I throw back "shots of the needful" with admirable equanimity, and shrink not from the more controversial questions, such as whether soupy Madeline Bassett believed stars were God's daisy chain or the wee sneezes of fairies.

Now, I do not claim the AFW in-character posts are unique. Very likely Dune-fanciers, Trekkies and even Shakespearians are boldly beaming each other up and wherefore-art-ing each other across the Internet. I certainly wouldn't put it past them. And I know from my '80s experiments with Dungeons and Dragons that role-playing is nothing new. I merely claim that I am playing in a way that I haven't done since my Barbie dolls were packed off to the Salvation Army, or since my friend Becca and I spent one happy summer in Narnia.

This kind of play was a continuous part of my reading life from my first encounter with "Pat the Bunny" until sometime around puberty. I was Oliver Twist the pickpocket, I was Jo in "Little Women," I was Peter Pan and Pippi Longstocking and some little witch whose name I don't remember. With my friends and alone in my bedroom, I made up fresh stories and fantasies based in the fictions I had first encountered on the page. And then, somehow, I stopped. My life as a reader changed. I wasn't Holden Caulfield, Owen Meany or Lily Bart. I was never anyone again -- until I became Lottie Blossom.

What had changed? With no fellow Peter Pans to urge me not to grow up, I had become concerned with my adolescent sense of dignity. I abandoned my series of imaginary characters in favor of fashioning my own identity in the real world. Then came college and graduate school -- where reading became a profession. Playing at it became unthinkable.

What ho, Plummies! They came to my rescue when I was mired in the depths of my dissertation, saving me from a life devoted to reading "Types of Ethical Theory" and Spinoza. The newsgroup gave me a sense of membership. They were a supportive group of completely invisible like-minded souls, unconcerned with dignity -- just looking about in search of a cocktail or a lost pig. In the safety of the Internet's anonymity, and in the jolly comfort of a shared language, I started playing again.

Offline, I'm not hopping about the apartment in search of my alligator or crying "What ho!" at my husband when he comes home, but Wodehouse's world infiltrates my life in pleasing and comical ways. For example, I prepared mind, body and soul for writing this essay by eating large gobs of English country lemon curd on toast and drinking tea. To get me in the M., don't you know. Later this evening, perhaps, I will restore the tissues with a drop or two of the needful. A boy who yells loudly in my building's hallway at all hours and then asks me to donate money to his scout troop is no longer an annoyance; he is an excrescence -- "as pestilential a stripling as ever wore khaki shorts and went spooring or whatever it is that these Boy Scouts do." Unlike Lotus, I am apt to be quiet in crowds, and to dress more like a janitor than a film star -- but something like Lottie's oomph has revealed itself in my recent purchase of some zebra-print shoes and a dress trimmed in feathers.

I probably won't ever become Holden Caulfield or Lily Bart. (Well, who would want to?) But being a fan has changed the way I read. I've shifted from my adult, over-trained intellectualism back to my youthful preoccupation and playfulness. And this way, I think, is better. Or as Plum would say, here I am -- all boomps-a-daisy.

Shares