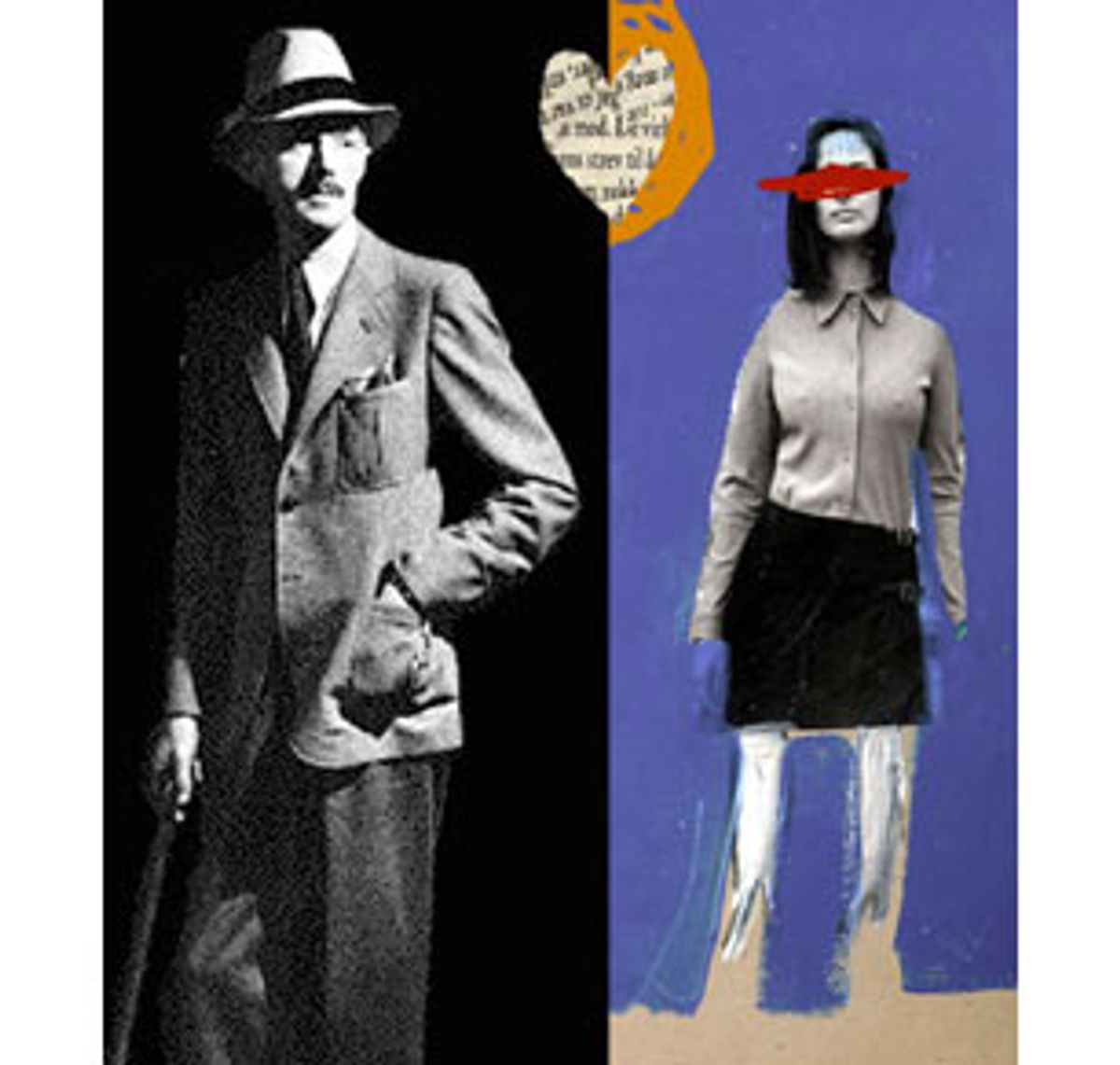

For an author who has been dead since 1961 and, more to the point, whose muse went south in 1934, Dashiell Hammett had quite a year in 1999. Knopf published "Nightmare Town," a collection of his long-neglected shorter works, edited by Kirby McCauley, Martin H. Greenberg and Ed Gorman. And a handsome, compact volume from the Library of America, "Dashiell Hammett: Complete Novels," marked the return to hardcover of the five full-length fictions that forged his reputation -- "Red Harvest," "The Dain Curse," "The Maltese Falcon," "The Glass Key" and "The Thin Man."

These two recent literary helpings of Hammett serve as notice to some and a reminder to others that there was a time when he was more famous for his fiction than for being Lillian Hellman's sparring partner and literary guru. They also suggest that his creative flow seems to have stemmed at the tail end of 1930. Earlier that year, he had completed the novel "The Glass Key." He also had begun a new manuscript, "The Thin Man," that he would eventually discard in favor of a very different sort of mystery with that same title. As he wrote to a friend, "My publisher and I agreed that it might be wise to postpone the publication of 'The Glass Key' ... So -- having plenty of time -- I put [the] 65 ["Thin Man"] pages aside and went to Hollywood for a year. One thing and/or another intervening after that, I didn't return to work on the story until a couple of years had passed -- and then I found it easier ... to start anew."

The "one thing and/or another" included the sale of "The Maltese Falcon" to Warner Bros., the signing of a contract with Paramount and, at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel ballroom on Nov. 22, 1930, a chance encounter with a script reader named Lillian Hellman that would radically change the remaining three decades of his life.

The short stories and novels written prior to 1931 are the works of an inventive, disciplined, dedicated author. The relatively little creative writing that he managed between 1931 and 1934, while certainly publishable and in most cases entertaining, didn't quite compare with what had come before.

Take the novels. The first four, the ones that set the pattern for the hard-boiled mystery, that intrigued (and probably influenced) such disparate writers as Andri Gide, Ernest Hemingway and William Gibson, that led an imprisoned Chester Himes from a life of crime into a life of crime fiction, seem pretty much undamaged by time. Six decades of other writers and filmmakers pecking at the bones of their plots have robbed them of some of their originality. But the tough, unsentimental, realistic style that prompted Raymond Chandler to label Hammett "the ace performer" is still very much alive and well on their pages.

"The Maltese Falcon," with its famous protagonist, Sam Spade, and a cast of unforgettable rogues and liars, remains the author's masterwork, one of this country's few genuine classic detective novels. (Not long ago, members of the Mystery Writers of America voted it the greatest crime book written by an American.) But its fame should not be allowed to cast too large a shadow over the other books.

Hammett's first two novels, "Red Harvest" and "The Dain Curse," are remarkable in their own right -- smartly plotted, visceral entertainments, moved along at a feverish pace by the lean and dramatic first-person narrative of their hero. That would be the fat and 40 Continental Op, an otherwise nameless troubleshooter for the Continental Detective Agency of San Francisco (said by Hammett to be based on Jimmy Wright, his mentor during his formative years as a Pinkerton investigator).

In "Harvest," the Op tries to restore order in a corrupt mining town in the Northwest that has been taken over by racketeers brought in to keep the mineworkers in line. It's a fictionalized account of the battles in Butte and Anaconda, Mont., between striking miners and the detectives and thugs hired by the mine owners to force the men back to work. The book has been the basis, uncredited, for three motion pictures, Akira Kurosawa's "Yojimbo," Sergio Leone's "A Fistful of Dollars" and the largely ignored 1996 Bruce Willis film "Last Man Standing," which was set in approximately the same period as the novel.

Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci tried for decades to translate the book into film without success. Perhaps this was because, as was told to me by his co-screenwriter, Marilyn Golden, they had changed the novel's warring gangsters into strikebreaking Pinkertons and union organizers. They were convinced Hammett would have approved, even though he'd chosen to disguise the opponents in the novel.

Both "Harvest" and "Curse" had their origins in the pulp detective magazine Black Mask, where each originally appeared as a quartet of linked novelettes. "Curse," in which the Op must save an addled young woman from an obsessed murderer, still shows its hinges, but makes up for it with some of the author's sparest prose and most striking imagery. It also presents a surprisingly dimensional portrait of the Op.

"The Glass Key," set in a fictional version of Baltimore, where Hammett grew up, focuses on Nick Beaumont, a shrewd and resourceful advisor to and best friend of a powerful city boss named Madvig. When the big guy falls hard for socialite Janet Henry, Beaumont, to prove that she isn't worthy of his pal, seduces her and then apparently falls in love with her himself. What makes the novel both frustrating and fascinating is the author's "what you see is what you get" presentation. While Hammett is careful to resolve the power struggle between Madvig and the crime boss, Shad, and to clear up the whodunit element, he offers little insight into what's going on in Beaumont's head. Is he really in love with Janet? Is he merely using her to better his own lot? Is he in love with Madvig?

The Op, a thorough professional whose main interest is in getting the job done, offers us some evidence of self-analysis. ("I've got horny skin over what's left of my soul.") Spade discards his cool objectivity to tell us that he's not the sort of guy who'll play the sap for anyone. Beaumont steadfastly refuses to give us a clue as to what he's thinking. Maybe his thoughts have been beaten out of him. Rarely has a protagonist been subject to so many blows to the head. (This point is amusingly made in "Miller's Crossing," the Coen brothers film unofficially based on "Key" in which Gabriel Byrne gets slugged every 10 or 15 minutes. Official movie adaptations in 1935 and 1942 featured, respectively, George Raft and Alan Ladd, two exemplars of the minimalist school of performing arts; they were ideal as the enigmatic Beaumont, with the Ladd version being a little better than average, thanks to a script by another hard-boiled master, Jonathan Latimer.)

The remarkable thing is that the book works so beautifully, no matter how you choose to interpret Beaumont's motives. Hammett considered it his best novel and others have agreed, including authors Somerset Maugham, Ellery Queen, Julian Symons and Rex Stout.

The Library of America collection clearly shows "The Thin Man" to be Hammett's weakest novel. Thanks to "Nightmare Town" -- among its pleasures is the author's discarded early draft, which editor McCauley has retitled "The First Thin Man" -- we can see precisely the effect that the movie money and booze and, yes, Hellman, had on his writing. The manuscript he began and put aside in 1930 (resurrected by Francis Ford Coppola's City magazine in a 1975 issue devoted to Hammett) has little in common with the published novel. "Some of the incidents in this original version I later used in 'After the Thin Man,' a motion picture sequel," Hammett wrote about the earlier start. "But, except for that and for the use of the characters' names Guild and Wynant (both recurring in the final version) this unfinished manuscript has a clear claim to virginity."

The original protagonist is private detective John Guild, a tanned, blue-eyed, steely brother to Spade and the Op. Though neither of those tough guys could be called sentimental, Guild lacks even their touch of the romantic. The guy is all work. His quarry is a missing scientist, the slim jim of the title, who has apparently murdered his secretary in a small community near San Francisco called Hell Bend. The 10 chapters have an economy of words and a purity of style that clearly identify their author. It is, however, Hammett's Black Mask style, strongly influenced by his experience as a Pinkerton Op.

By the time he returned to the project, he was a changed man -- a financial and literary success and an accepted member of an intellectual crowd of novelists and screenwriters that included William Faulkner, Ben Hecht and Dorothy Parker. Feeling it was time to move on to a different kind of book, he discarded the tight, hard-boiled West Coast thriller in favor of a more "sophisticated" Manhattan sort of novel -- a mystery-comedy of manners in which a witty and wealthy young bicoastal couple, Nick and Nora Charles, interrupt their Christmastime partying in the big city to solve a murder or two.

In the past, Hammett had used his experiences as a detective to fuel his fiction. Now he was relying on his present lifestyle. He told Hellman she was the basis for Nora. It doesn't take a master's in lit to figure out his inspiration for Nick, an alcoholic ex-detective who has opted for an indolent life over a meaningful occupation.

"The Thin Man" isn't a disaster by any means. The dialogue has wit. Nick and Nora, at least on the surface, are charming and good company. The story moves along nicely. By most standards, it would be considered a prime example of a bracing whodunit. But it isn't in the same league with Hammett's other, meticulously crafted books. Alfred Knopf, his publisher, may have known this. He tried to inflate sales with a full-page ad in the New York Times, calling attention to the novel's then-daring use of the word "erection." He needn't have bothered. "The Thin Man" was a hit. Still, in an interview in 1957, Hammett said that he had always found the novel boring. It was probably his most financially rewarding work, spinning off into six much-beloved motion pictures (in which William Powell and Myrna Loy had such wonderful chemistry it was easy to overlook the shallowness of their lives), a long-running radio program, a television series and, in 1992, a Broadway musical.

All of Hammett's novels have been in print for decades, though primarily in paperback. His upwards of 70 shorter pieces have had a spottier history. He preferred it that way, considering them products of an earlier, pulpier time in his career. In the mid-1940s, however, author and editor Ellery Queen (the pseudonym used by cousins Manfred B. Lee and Frederic Dannay) talked him into freeing a handful of the short stories for a limited-run trade paperback edition. Its success led to a second collection, then a third, until a total of nine Queen-edited collections were published. Regardless of their popularity, Hammett was adamant that the stories never appear in hardcover or mass-market editions.

After his death in 1961 (from a combination of lung cancer, emphysema and heart disease), according to his wishes Hellman was appointed executor of his estate. Though she guarded her real or imagined memory of him with an unwavering possessiveness that became the bane of would-be biographers, she was not averse to putting his pulp fiction back into print. As Joan Mellen notes in her hefty, fact-filled 1996 joint biography, "Hellman and Hammett" (Harper Collins), the playwright had a financial as well as a romantic interest in Dash's past. She had purchased the rights to much of his literary work from the estate. Mellen devotes pages and pages to the methods she employed to secure the copyrights, often acting in apparent opposition to the dictates of Hammett's will, which stated that only a quarter of his assets was to go to her. An additional 25 percent was to go to his adopted daughter, Mary, and 50 percent to his biological daughter, Jo. Mellen quotes Hellman as saying, "I bought the estate. I'll leave them something when I die."

In 1966, she edited the first hardcover collection of Hammett stories, "The Big Knockover." It consisted of nine of the best Continental Op novelettes and "Tulip," a rather painful beginning to a stalled autobiographical novel. In 1974, she granted Random House permission to bring out a second volume, "The Continental Op," edited by literary historian and Columbia University professor Stephen Marcus (who also provided a chronology and notes for the Library of America collection). Together, the two books put 16 of the Op stories back into print. That barely scratched the surface of the material Queen had unearthed, as editor McCauley came to realize five years ago.

"It took me about a year to get around to discovering that the agency that handled the novels wasn't the same one that handled the stories," he told me recently. "They gave me a tentative OK to put the collection together, and that took another year. Then there was the time spent by the lawyers at Random House and the lawyers for the estate. It wasn't that unusual a situation. I'm a literary agent myself, and I know you run into these complications with estates. There are always a lot of people that have to be consulted."

Though McCauley wouldn't say so, this one was probably a little more complicated than most. Mellen's biography states that Hellman's will arranged for her own literary executors to make all decisions concerning "the use, disposition, retention and control of the works of Dashiell Hammett, both published and unpublished." In other words, everything pertaining to his estate has to flow through her estate.

"Once the book started to fall together," McCauley says, "it went very quickly." He and co-editors Greenberg and Gorman settled on 20 tales, more than in the two previous collections combined, that cover a comprehensive, 11-year span. Again, the earlier work outshines the post-1930 stories.

The former are represented by seven diamond-hard Continental Op capers and a few other gems. "Ruffian's Wife" is told from the point of view of a sensitive woman married to a swaggering adventurer who clearly doesn't understand her. "The Second-Story Angel," an O. Henry-like short story, has an ending that manages not only to surprise, but to do so in a way that mocks romance and satirizes pulp writers.

The comparatively fewer selections from the '30s, written primarily for slick magazine money, are typified by three Sam Spade stories -- "A Man Called Spade," "They Can Only Hang You Once" and "Too Many Have Lived" -- all of which lack the painstaking care and technique that Hammett brought to his pulp work. "Hang" does have the distinction of a terrific opening line: "Sam Spade said: 'My name is Ronald Ames.'" Past that, it is an inferior reworking of the Continental Op short, "Night Shots," which, purposefully or not, is also part of this collection.

What "Complete Novels" and "Nightmare Town" do not do, and what no amount of literary truffle hounding or biographical interpretation has been able to accomplish, is to solve definitively the mystery of Hammett's 27-year-long writer's block. Whodunit? Whydunit? And what in the world could he have been thinking and/or drinking that night in 1930 when he fell under Hellman's spell?

Shares