This fall marked the centennial of "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz," the quintessential American children's fantasy. It's also the 50th anniversary of C.S. Lewis' "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe," a book that would rate as the jewel in the crown of the British branch of the genre if the competition weren't so formidable. While W.W. Norton celebrates Oz's milestone with the publication of a new hardcover edition of Baum scholar Michael Patrick Hearn's "The Annotated Wizard of Oz," Lewis' book is getting a desultory commemoration from HarperCollins -- new editions of the seven-book Chronicles of Narnia series with the original illustrations colorized and laminated paperback bindings.

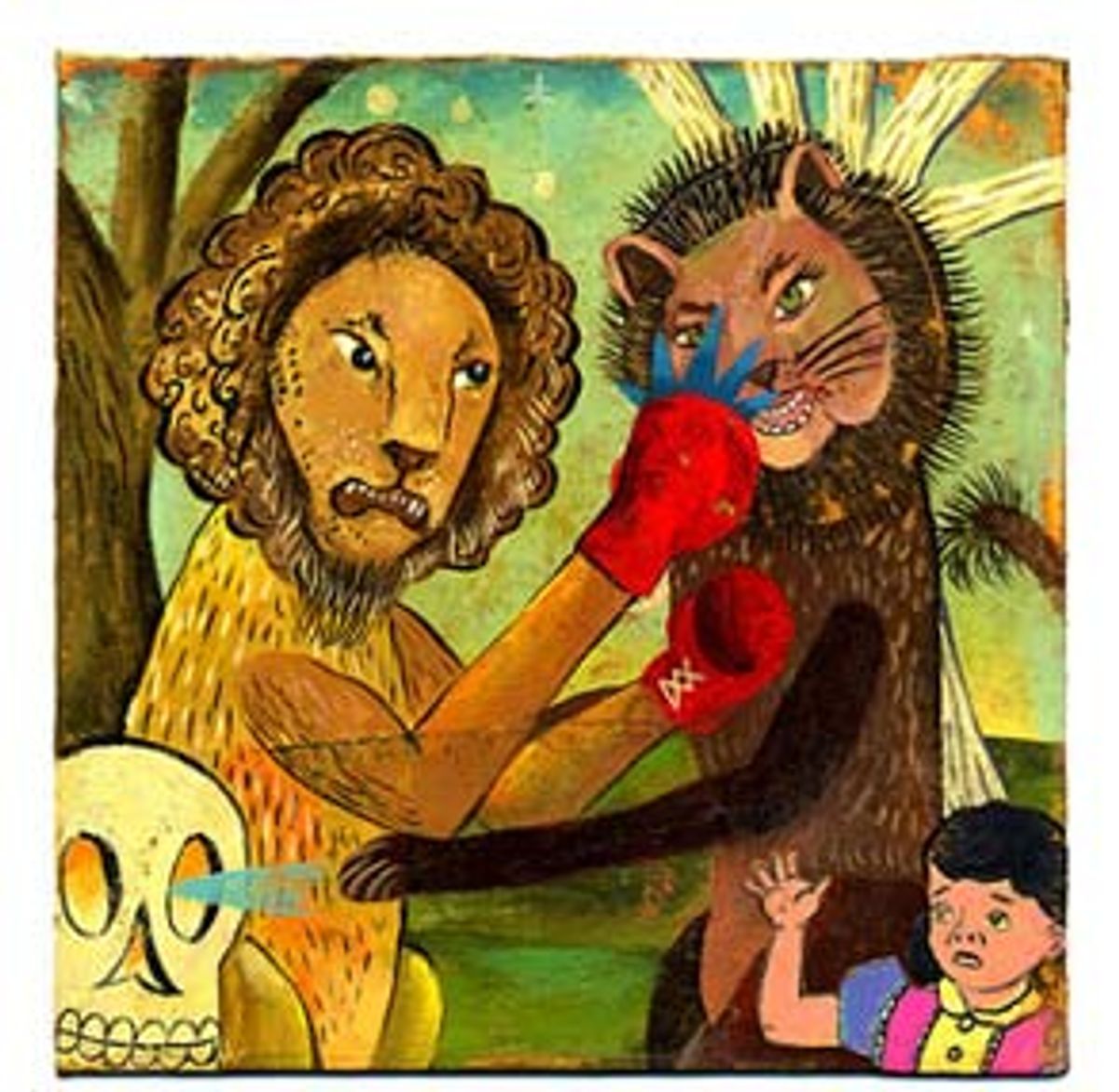

But however much the tribute to Oz exceeds the tribute to Narnia in sumptuousness, it can't disguise the superiority of Lewis' book. As a child, I loved Oz's endless cavalcade of strange creatures and, especially, John R. Neil's trippy art nouveau illustrations and extravagant marginalia; I still like the books today. But the first time I read "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" in second grade, I knew that I'd stumbled into a whole new league. That's not surprising, since British children's books, particularly children's fantasy, have long been notably better than their American equivalents -- deeper and richer. The joint anniversary of these two classics offers an irresistible opportunity to ask why, and to see whether the difference says something fundamental and troubling about how Americans understand ourselves and our children.

Hearn's new "Annotated Oz" contains a facsimile version of the original "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz," complete with its innovative single-color textual illustrations (a different color for each chapter) by W.W. Denslow. There's a lengthy introduction describing Baum's life and almost dementedly varied career, Hearn's extensive notes on everything from character names to puns to the possible religious and political interpretations of the book and literary commentary on Baum's prose that's generous to a fault -- well, actually, way beyond a fault.

The model for this volume is Martin Gardner's successful annotated version of Lewis Carroll's "Alice in Wonderland." But while Carroll's children's classic is full of double meanings, mathematical jokes, puzzles, political satire and witty digs at the pomposity of Victorian culture (particularly the poems children were made to memorize), Baum's fairy tale is plainer stuff. Although a man of considerable energy and warmth, Baum was no intellectual and not inclined to subtle allegories, irony or comprehensive systems of hidden meaning -- he wasn't meticulous enough for that, as the many contradictions in the Oz cosmology show. That hasn't stopped his fans from trying, though, and I confess I was a little crestfallen to discover that no one really credits the theory (advanced by one Henry M. Littlefield) that "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" is an elaborate symbolic commentary on William Jennings Bryan and the gold standard.

Baum no doubt revealed his full intentions in his original introduction to the book. He aspired, he announced, to write a "modernized fairy tale," from which both morality and "all the horrible and blood-curdling incident" found in traditional fairy tales had been removed. This sanitizing could at last be achieved because "modern education includes morality," and the only reason for all that scary stuff in the first place was to back up a story's moral with some serious firepower. Anyone surprised to read that pre-modern education methods omitted morality will nonetheless be comforted to learn that in this book "the wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out."

"The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" (the book) has become so closely meshed with "The Wizard of Oz" (the movie) that people often forget that the book has nothing scary or even unsettling in it. The filmmakers apparently didn't share Baum's faith in "modern education"; Margaret Hamilton provides plenty of real menace both as a malevolent adult in Dorothy's real life and as an outright terrifying, green-faced Wicked Witch of the West in the dream world of Oz. Her literary forebear is ineffectual by comparison; she can't harm Dorothy because the little girl bears the mark of the kiss of the Good Witch of the North on her forehead, and the villainess would like to steal her prisoner's magic silver shoes but she's too afraid of the dark to sneak into Dorothy's room at night. The worst torment the witch can devise for the girl is to make her do housework.

In later books in the series, Baum explained that no one in Oz ever dies, ages or gets sick. There are several minor events in "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" that violate this rule, but the main characters are never in mortal danger; even when the Scarecrow is unstuffed by the flying monkeys and his cloth casing is thrown up in a tree, he can be easily restored. Baum promised one interviewer, "You'll never find anything in my fairy tales which frightens a child."

Many adults today think J.K. Rowling should have followed Baum's example instead of writing the death of a sympathetic character into "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire," the first of several dark moments to come in the series, according to the author. Rowling, however, remains adamant that to pretend that loss, pain and fear aren't a part of life would be to weaken and trivialize her series, and she need look no further than Baum's Oz books for a cautionary example.

There is wickedness in Oz, but no evil; badness is simply a disagreeable temperament certain people have, not a terrible force at work in the world, certainly never a temptation to any of the heroes. Character is fixed, and no one really changes. Dorothy remains exactly the same, "a simple, sweet and true little girl," throughout the entire series, and at the end of their adventures, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Cowardly Lion learn that they were already smart, kindhearted and brave. The answer to life's perplexities is to realize how terrific you already are, an aspect of Oz that seems one of its most American traits.

Then there's the universal narcissism of the characters. Social conversation in Oz consists almost entirely of creatures explaining themselves to each other. It weirdly resembles the brandishing of identity credentials seen in certain graduate seminars, with "as a working-class lesbian ..." replaced by "as a scarecrow ..." In a typical disquisition, the straw man announces, "I am never hungry, and it is a lucky thing I am not. For my mouth is only painted, and if I should cut a hole in it so I could eat, the straw I am stuffed with would come out, and that would spoil the shape of my head."

Whatever makes Americans want to go on national television to natter on about the joys and trials of being a transvestite or a born-again Christian stripper obviously predates the mass media. (Perhaps Baum picked up this way of talking while he was working as a traveling salesman?) The Ozian symphony of self-involvement reaches its crescendo when the Wizard's true identity has been revealed and the four pilgrims lament their dashed hopes. "I pray you not to speak of these little things," the humbug interrupts. "Think of me, and the terrible trouble I'm in at being found out."

Oz is also, with a creepy prescience, a nation where personality determines politics. A little girl becomes a princess or a tin woodman is suddenly made Emperor of the Winkies simply because "the people" -- an indistinguishable mass of plump, contented burghers -- are "so fond" of them. The fatuous, Rotarian club notion of "goodness" Baum advances is, like the wickedness of his villains, a disposition rather than a practice, and its fruits are given rather than won; likability is all it amounts to.

The literary gulf between "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" and "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" is partly a matter of sheer talent; Baum never wrote a deft sentence, while Lewis excelled at them. Hearn touts a scene in which the Scarecrow, gathering nuts for Dorothy to eat, finds the little objects hard to pick up with his clumsy, padded fingers, as an example of "how skillfully Baum fills his tale with little easily missed but defining items which vividly bring his characters to life." A friend of Baum's once described him as having a "strong leaning towards technical matters," and that's what Hearn's "defining item" regarding the scarecrow is: engineering as character. Compare it with this scene in which Lewis' four child protagonists, led in their desperate flight from the White Witch by a talking beaver, reach a frozen river with a dam built across it:

They noticed that [Mr. Beaver] now had a sort of modest expression on his face -- the sort of look people have when you are visiting a garden they've made or reading a story they've written. So it was only common politeness when Susan said, "What a lovely dam!" And Mr. Beaver didn't say "Hush" this time but "Merely a trifle! Merely a trifle! And it isn't really finished!"

That's the kind of droll characterization you have to be adult to notice, just as I only recognized the limpid beauty of Lewis' descriptions of the Narnian countryside when I reread his books as a grown-up, but even an unsophisticated reader will fall under the spell of both. At 8, I only knew that "The Chronicles of Narnia" was potent stuff, and it never would have occurred to me to wonder how. And while most children won't grasp what a mediocre writer Baum is, it's telling that an author who could never have pleased a discriminating adult readership became one of America's foremost kids writers.

Hearn complains that American librarians have unjustly labeled Baum's Oz books as "poorly written"; the librarians, however, are right. He attributes their preference for British fantasy to "Anglocentric" "reverse snobbism," but the truth is that in Britain real writers like Lewis (and J.R.R. Tolkien, and J.K. Rowling and Phillip Pullman today) write children's fantasy, and they take their readers seriously, as people facing a difficult and often confusing world.

We'll probably never see an annotated "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" because the Christian elements in Lewis' work repel interesting critics and scholars -- some of whom are still embarrassed about how much they liked his books as kids. (Lewis scholarship exists, but it's a hagiographic wasteland roamed by worshipful, third-rate Christian academics who see his work as something close to divine revelation.) Former fans often (mistakenly) dismiss his children's books as simple religious allegories, and the well-earned reputation that Christians have for smug proselytizing has tarnished much of Lewis' writing by association.

It's a shame because "The Chronicles of Narnia" is a fascinating attempt to compress an almost druidic reverence for wild nature, Arthurian romance, Germanic folklore, the courtly poetry of Renaissance England and the fantastic beasts of Greek and Norse mythology into an entirely reimagined version of what's tritely called "the greatest story ever told." Even if you don't agree that it's the greatest story, it's still one of the great ones, and Lewis -- a leading literary scholar of his generation and a writer of uncommon eloquence -- not only set himself a mighty task but pulled it off. This is British children's fantasy -- a far cry from the modest American talent who leads with a promise to dispense with all "disagreeable incident."

Just as the British think that children are important enough to merit the work of their best writers, British children's writers think children are important enough to be treated as moral beings. That means that sometimes things get scary. The four children -- Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy -- in "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" have not just their own distinct personalities but their own private tests; though they too wind up as kings and queens of a magical land after saving it from an evil witch, they have to fight, hard, for their crowns. Lewis' depiction of what it means to be tempted by evil, as Edmund is by the White Witch when she plays on his vanity, and of the behavior -- from petty cruelty to grave betrayal -- that results, made a tremendous impression on me as a child. It communicated that, faced with often deceptive and even self-destructive emotions and impulses, I had choices to make in my life, choices that mattered.

Baum, like many Americans today, saw children differently, as pure innocents who need to be shielded for as long as possible from the challenges of life. "There should never be anything except sweetness and happiness in the Oz books," he told a friend, "never a hint of tragedy or horror. They were intended to reflect the world as it appears to the eye and imagination of a child." While the sentiment is genial, that's all it is: sentiment. Even children themselves find that sort of talk annoying. That's why they greet the deliciously dour books by Lemony Snicket with such glee: The meddlesome protectiveness of adults has made reading sad stories about unfortunate events a naughty pleasure.

Beyond a bit of healthy rebellion, though, you can't blame children for resenting adults who'd like to keep them in a rosy bubble, far away from reality's shocks. A life without risks or danger is a life in which nothing important can ever happen. It's also a pipe dream. Children, like everyone else in the world, encounter situations that force them to decide between their best and worst impulses -- whether or not to side with a picked-on schoolmate, for example. The bumpy journey from the blithe egotism of infants (and Baum's Ozians) to a larger understanding starts early, and the kids who make the best adults know that growing up is their big adventure, not a fall from grace. Just because the readers are little doesn't mean the stories have to be small.

Shares