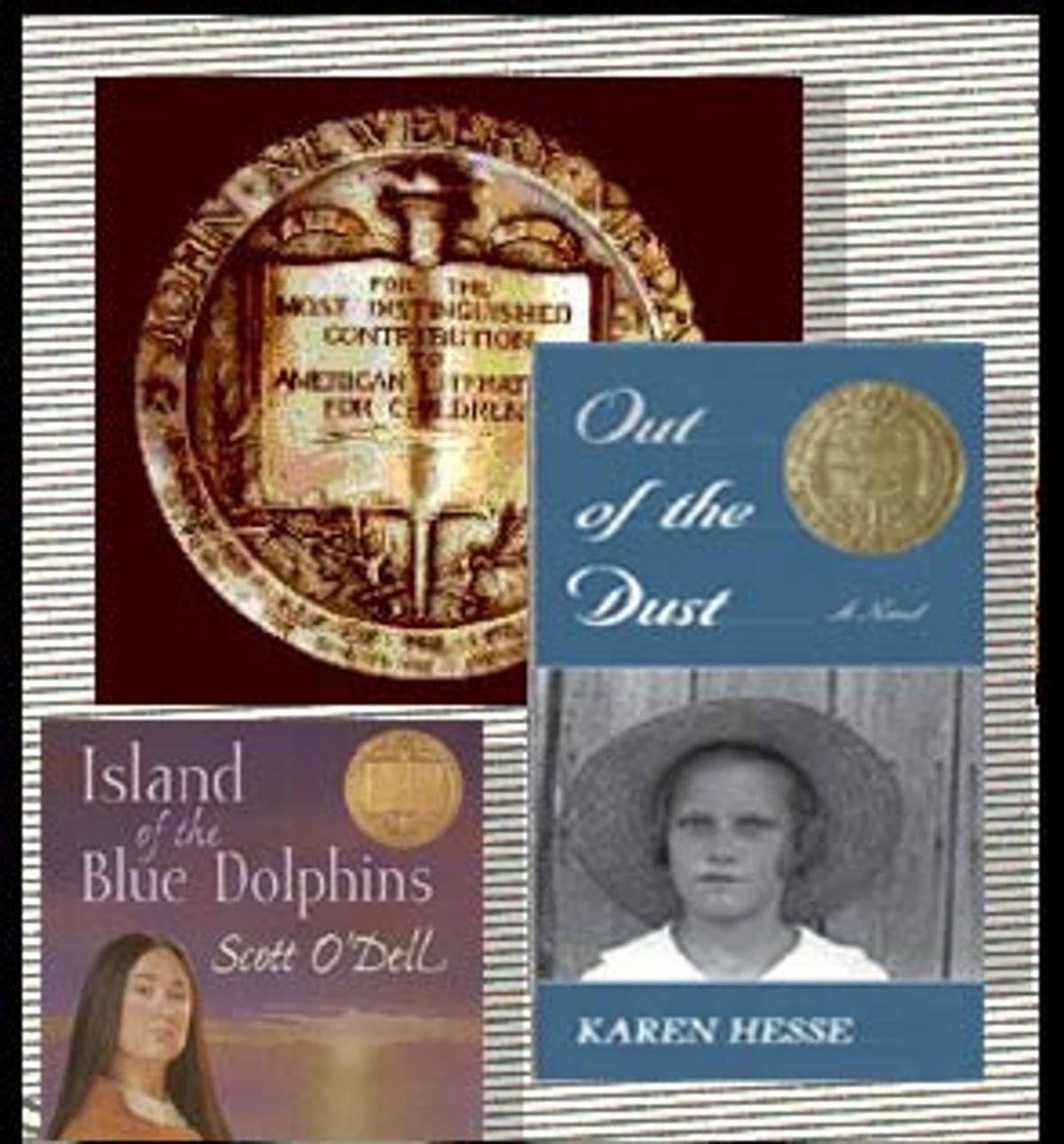

As a bookish child I didn't simply dislike the Newbery books. I feared them. I abhorred them. The one I hated most was an appallingly miserable story: A native girl is abandoned on an island, finds her baby brother killed by wild dogs and scrapes out a living alone for 18 years. I've got nothing against desolation -- I'm a DeLillo fan -- but that book did me in. And if the books didn't thrust me into someone's story of dismal loss and painful poverty, they were so boring that I learned to treat the Newbery's gold-foil stickers as warning labels. And so when, last week, I heard that the latest Newbery had been awarded to a book about a Depression-era girl sent to live in hardscrabble Illinois with her difficult grandmother -- can you say "educational"? -- the announcement triggered a PTSD flashback, and made me question again the Newbery list.

Why is the Newbery medal treated as nearly infallible, unlike every other literary award? From critics to book group members, from solitary readers to bookstore owners, bibliophiles love to quarrel with the choices of those who pick the Pulitzer, the Booker and the Oprah moment winners. Nobody assumed that Susan Sontag's "In America" was spectacular just because it won the most recent National Book Award for fiction; we know that while some prizewinning books are extraordinary, others are at best forgettable. But when the Newbery medal gets awarded to "the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children published in the United States during the preceding year," adult readers suspend their own judgment and accept that of the experts. Newbery medalists immediately sell 100,000 copies -- bought by every children's library in the country and by many parents and grandparents without a second thought -- and stay in print forever.

We should know better. Most of the people I've asked remember the Newbery medalists as the "boring" books, the books that stayed on display at the library because no one checked them out. There's a reason for that memory. No one who reads for pleasure and challenge and joy would willingly subject themselves to such demeaningly tedious books as the 1959 winner "The Witch of Blackbird Pond," the 1962 winner "The Bronze Bow," the 1974 book "The Slave Dancer" or the 1998 snorer "Out of the Dust." Their neon-bright messages flash clearly: religious prejudice is wrong; slavery is wrong; poverty is bad. Yes, inspired authors -- for instance, Arthur Miller, Toni Morrison and John Steinbeck -- can and have written gripping, even brilliant fictions about subjects like witch hunts, slavery and dustbowl poverty. So why, instead of delightful and powerful fictions, give children these other insomnia-curing books written in terrifyingly earnest and plodding prose, full of stick figures -- books as free of passion as a bad educational documentary, books that could turn an imaginative child into a dedicated television fan?

Worse, while eat-your-spinach books were getting Newbery medals, truly brilliant books were overlooked. Instead of "The Bronze Bow," the 1962 Newbery could have gone to Norton Juster's "The Phantom Tollbooth;" instead of the forgotten title "Shadow of a Bull," 1965's award could have gone to Louise Fitzhugh's "Harriet the Spy."

These two miraculous books changed not only my life but the lives of book-worshipping children all over the country; mentioning them can jump-start idling conversations among ex-children at many an American dinner party. Juster's bored and mildly depressed Milo and Fitzhugh's butchy misfit Harriet were breakthrough characters, children who were -- like their readers -- bloodying their knees at the rocky edge of adulthood, trying to make sense of a bewildering world in which one had to figure out impossible paradoxes just to get through a day. Harriet and Milo are as different as possible from the nearly invisible main character of the Newbery book I particularly despised, 1959's "Island of the Blue Dolphins," which on rereading turned out to be a grim compilation of facts, a Mutual of Omaha nature special about the flora and fauna of the island with scarcely a scrap of the abandoned girl's inner life.

Which is not to say that all Newbery medalists are as dull as dust. The medal has landed on some wonderful books. Even during the 1960s and 1970s, which may have been the award's nadir, the Newbery found such compelling books as Madeleine L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time," E.L. Konigsburg's "From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler" and Virginia Hamilton's "M.C. Higgins, the Great." Its most recent spectacular find is the 1999 Newbery winner, Louis Sachar's "Holes," which I couldn't put down, an intricately plotted and beautifully written tale of despair and redemption, in which a boy is exiled to a brutal juvenile correction camp in the desert for a theft he didn't commit, a story that begins as hyperrealism and opens up, with deadpan absurdity, into interlocking tall tales of family mythology, fate and freedom.

In fact, only one of the 1990s medal-winners that I read was as dutiful and boring as the Newbery medalists of my 1960s childhood. But that doesn't mean the Newbery winners are now perfect. Most recent winners are solid B, B minus or B plus books, boppy and superficial, albeit clever and well-written. This year's winner, Richard Peck's "A Year Down Yonder," is one such readable if mediocre offering. Its feisty rural granny is entertaining, and you do learn how to shoot a fox, but its 15-year-old "main" character scarcely exists.

That's a serious flaw -- because what makes the difference between a memorable and a tiresome children's book is how believably the characters struggle with the gap between emotions and actions, between what should be and what is. At 10 and 12 and 14, kids are in such dorky-looking and angry pain partly because they're just beginning to realize that life demands that, like the White Queen, they must practice believing six impossible things before breakfast. Childhood is a passionate battle to make sense of the world, to reconcile apparently polar but deeply tangled opposites: right and wrong, safety and freedom, responsibility and desire, honesty and kindness, fear and courage, bullies and friends, parents who are heroic and loving and parents who are deceptive and fallible.

Childhood is, in other words, very much like adulthood. That's why a good adult book often makes a good child's book -- Michener was my favorite author at 13 (supplemented by "Fear of Flying," which circulated secretly in study hall), Steinbeck at 14, Tolstoy at 15 -- and vice versa, as when the Harry Potter series swept the New York Times bestseller list.

So why do so many adults give such unquestioning respect to the Newbery awards, even though we remember perfectly well that our favorite books weren't Newbery medalists? Surely the answer grows partly from the 20th century's long strange trend toward treating children as a separate species, as pre-human animalcules who must be segregated from adult work and play, who require special mental nutrients if their fragile little brains are to grow properly.

Far too many parents, crazy with anxiety about raising their children right, hand off their judgment to experts ranging from Dr. Spock to Dr. Brazelton, from Parenting magazine to the Newbery medal. It's no surprise that the Newbery medal dates from 1922, a pivotal time in the invention of childhood. Even as late as the 1930s the new category of children's literature hadn't fully taken hold: My mother-in-law, now an omnivorous and sophisticated reader, remembers reading through a complete set of Dickens, and then tackling anything else she could understand from her parents' library.

But I suspect there's a more personal reason that many adult readers unquestioningly and uncritically accept the Newbery medal: because many of us were well-trained and obedient children, children who respected authority. Bookish kids were often the homework-doers, the good-grade-getters, the ones who took our vitamins and sat still for the eye doctor. When we rebelled we did so sneakily, with a flashlight under the covers. And so lurking in the back of many minds is an atavistic belief that the grownups are always right -- that the books we were sneaking for pleasure weren't as good for us as the award-winners we should have been reading. We too often treat the Newbery awards as if we were still children being told what's good and what's bad, what's right and what's wrong.

It's time we adults grew up -- and start thinking of the Newbery medalists as suggestions, not final judgments. It's time to stop treating children -- the children we were, the children we know now -- as less perceptive and emotionally sophisticated than they are. It's time to chase away that lurking childhood belief that the ALA's committee of librarians -- the experts -- has some special insight into what children want to and should read. Before you buy a Newbery book for your daughter, your nephew, your young friend -- or yourself -- start reading. See how long it keeps you riveted. Ask yourself whether you'd rather read that or "Anne of Green Gables," "Tom Sawyer," Edith Hamilton's Greek myths, "My Antonia," "Annie John," "To Kill a Mockingbird," "War and Peace" or any other truly memorable book. Your guess may well be as good as the ALA's.

Shares