The bland yellow courtroom in London's Royal Courts of Justice is an odd setting for a debate about the Holocaust. The questions sound like the start of tasteless jokes: How much hydrogen-cyanide gas does it take to kill a room full of people? How many corpses fit onto an elevator floor? How many people can one gassing van deliver to death in a day?

Yet the answers have become pieces of evidence in a British libel trial that litigants on both sides hope will define the parameters of debate about what many call the greatest moral crime of the 20th century.

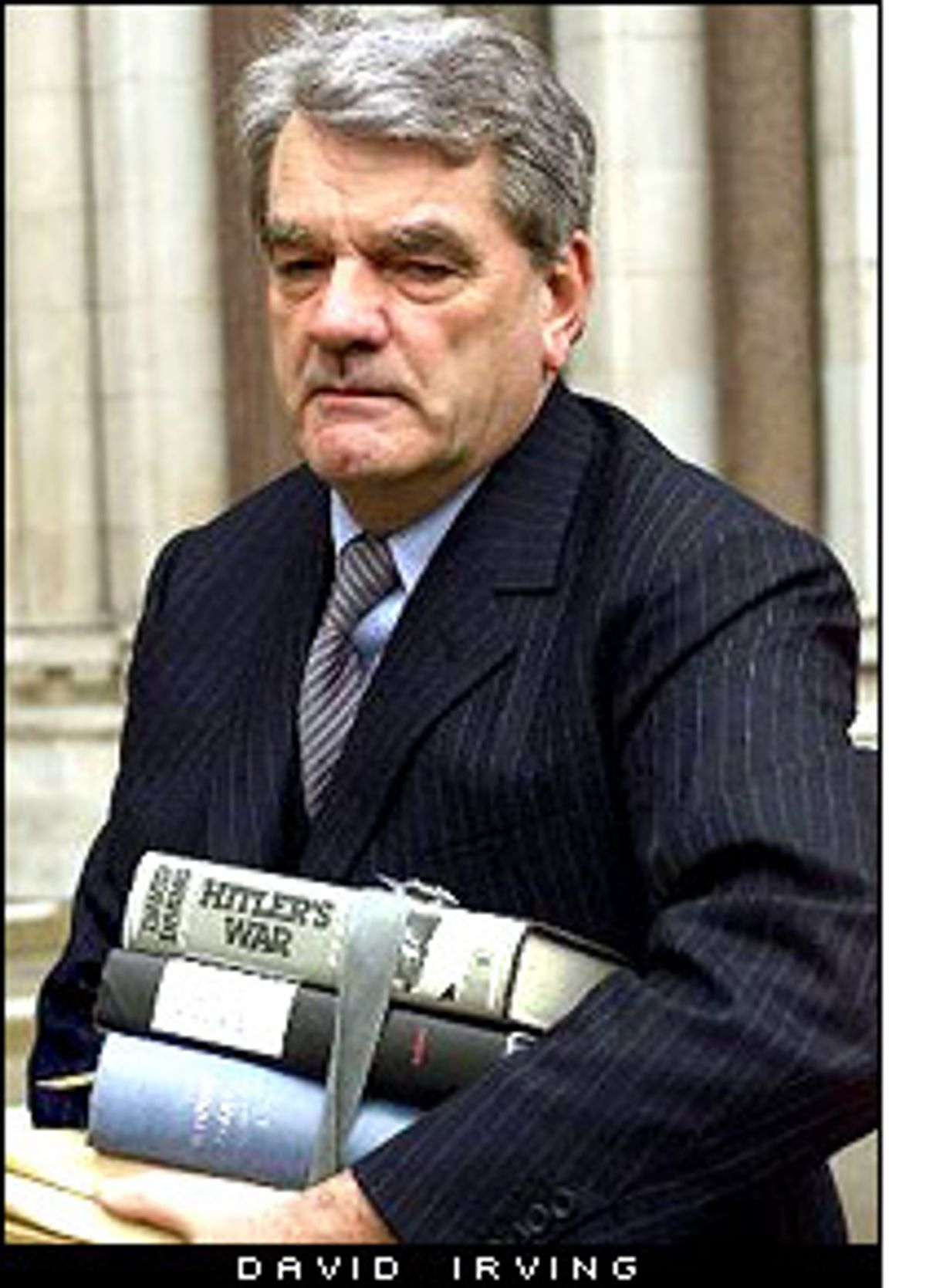

On one side of the fluorescent-lit courtroom stands the British author David Irving -- revisionist historian, Hitler apologist or liar, depending on whom you ask -- who does not believe the Nazis systematically killed Jews in World War II. They died, he says, from disease or by the hand of "rogue Nazis." Irving stands alone on his side of the courtroom, for he has chosen to represent himself in a case that both sides agree is so complicated that a judge, and not a jury, should hear it.

On the other side of the room sits the target of his suit, Deborah Lipstadt, a professor from Emory University in Atlanta, Ga., who wrote "Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory." Lipstadt, Emory's Dorot Chair in Modern Jewish and Holocaust Studies, called Irving "one of the most dangerous spokespersons for Holocaust denial." She and others criticized his American publisher, St. Martin's Press, for picking up his latest book, "Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich," in 1996. The book was dropped before it was published.

Lipstadt and a representative from her fellow defendant, Penguin Books Ltd. (UK), are surrounded by a team of black-robed English lawyers and university researchers, all paging through files, leafing through books, typing notes on laptop computers and writing messages to each other on Post-it notes.

British law divides the duties of attorneys in a courtroom, between the solicitor who gathers the evidence and builds the case, and the wig-wearing barrister who puts these arguments to the judge. Lipstadt has a star team: Her solicitor is Anthony Julius, who represented Princess Diana in her divorce. Her barrister is Queen's Counsel Richard Rampton, a big name in British libel circles.

Both sides plead their case to Justice Charles Gray, formerly a premier libel lawyer himself and a relative newcomer to the bench. Gray has given Irving great leeway in presenting his case, for fear of putting a person with no legal experience at a disadvantage. The trial, which began Jan. 11, is scheduled to last three months.

If this were an American libel court, the judge and barristers would not wear wigs and Irving would have the burden to prove he'd been defamed ("with malice" in his case, as with all public figures). But this is a British libel court, and the burden is on the defense to prove Lipstadt told the truth when she wrote that Irving bends historical evidence "until it conforms with his ideological leanings."

Barrister Rampton's job -- which he does while pacing, tying the sleeves of his robe behind his back and adjusting his wig -- is to prove Irving deliberately misread, misinterpreted or missed key historical documents.

Irving's differences with the vast body of Holocaust scholarship are not subtle. He does not think gas chambers existed for mass extermination. They were used, he says, to delouse clothes and disinfect corpses. He does not believe Hitler devised the Final Solution.

The word "Holocaust" was removed from the second edition of his book "Hitler's War," because he finds the term "misleading, offensive and unhelpful. It is too vague, it is imprecise, it is unscientific and it should be avoided like the plague."

Despite this, Irving claims Lipstadt defamed him by labeling him a "Holocaust denier," marking him with "a verbal Yellow Star."

But the British author is after what he sees as a bigger enemy, as well. He says his reputation has been destroyed by an "organized international endeavor," which, upon closer inspection, comprises mostly Jewish lobby groups like the Anti-Defamation League and the Board of Deputies of British Jews. Their members have prevented him from publishing his books, speaking at universities and traveling to certain countries, he says.

Irving is banned even from Germany, where he has done much of the 40-odd years of research for his 30 books, because he violated that country's law against denying the Holocaust.

This week the trial's big news was Israel's decision to release the pre-execution memoirs of Adolf Eichmann, to help Lipstadt with her case. The computer disk containing an estimated 600 pages was handed over to Irving after he promised not to publish it on his Web site.

Irving is good at sliding out from many of the accusations against him. It is true, as he has argued at the trial, that historians do "make mistakes" and can be "caught out by fresh documents that come into their purview." And in fact, scholars debate when the Final Solution became the Nazi answer to the "Jewish question," as well as other important facets of the Holocaust. Irving posits himself as a man taking part in these debates.

There is no "smoking gun" order from Hitler calling for the destruction of the Jews, he reminds the court often. There is no "smoking gun" blueprint for gas chambers at Auschwitz.

And, of course, he is right.

On the surface he sounds believable. His tall, square-shouldered frame reflects his inner confidence over a mastery of obscure Nazi documents and wartime history. He bounces on his feet as he fences verbally with Rampton.

His comments cause a flurry of scribbling, as Holocaust survivors, Irving supporters, tourists, law students, professors and scruffy courthouse regulars take notes on whatever is available: envelopes, small notepads, newspapers. Reporters from Germany, Israel, Australia and the United States sit nearby, filling notebooks with Irving's words and the arguments from the defense. Most days the stern court clerk places a "Court Full" sign on the door, barring entry to more who wait in the narrow corridor.

Sometimes the trial is a jousting match, with historical documents and incidents as the lances. "What do you take to be the meaning of the phrase found in Wetzel's letter to Lohse of 25th October 1941 ..." starts Rampton, and Irving shoots back: "I am familiar, you remember, with the Tesch trial ..."

Other times, the debate is more disturbing:

"They also retrieved a paper sack, marked on it a weight of 25.5 kilograms of hair, which they say was taken from the corpses of females after gassing and before burning in the crematorium ovens in Birkenhau," said Rampton. "Twenty-five point five kilograms of hair in total is the hair of about, what, 500 women?"

"I do not know," Irving answered. "I have not done any calculations. It seems to me you would have had to have a bag the size of an elephant to make it weigh 50 pounds of human hair."

The living faces of the Holocaust visit the trial as well. Michael Lee, a 76-year-old survivor of Auschwitz, comes every week.

"The whole thing is surreal to me," he said. "I can't believe they argue dates and translations of words when I actually witnessed the horror of the whole thing."

People like Irving worry him, he said, because they plant seeds of doubt. "Now there are a lot of witnesses still alive," he said, "but in 20, 30, 40 years there won't be anybody left."

But Irving argues that even the testimony of survivors and eyewitnesses is unreliable. He rejects all eyewitness testimony about gas chambers at Auschwitz, for instance, most of it presented during the Nuremberg trials after the war. He thinks former camp officials lied to cooperate with Allied investigators to save their necks, and former inmates trumped up stories as revenge on their captors. On the other hand, he accepts without skepticism accounts by Hitler's adjutants when they exonerate the Fuhrer.

And while Irving accuses "establishment" historians of overlooking documents he has discovered, he rejects out of hand key documents that have been a foundation of mainstream Holocaust history. He ignores, for instance, the astounding death tolls listed in reports from the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile killing units that shot Jews and communists caught behind the German advance eastward. (One report listed 363,211 Jews killed in the last third of 1942.) Such figures are probably inflated, he said, to "show off."

Other times Irving defends himself by saying he just made mistakes. He misread an "order from Hitler" to SS leader Heinrich Himmler to spare one trainload of Jews from Berlin as an order to spare all Jews. Further probing by the defense showed Himmler issued the order before meeting with Hitler anyway.

But the defense says Irving's "mistakes" and interpretations point in one direction only: toward the exculpation of Hitler and the denial of the systematic slaughter of the Jews because they were Jews.

The defense has also tried to link Irving's mistakes to what it describes as his racism and right-wing ideological bent. For two days the court listened to Irving's past speeches in which he said black news anchors should be allowed to report only on muggings and drug busts, and that he "shuddered" to have his passport checked at British immigration control by a "Pakistani." The defense recited a rhyme Irving taught his 9-month-old daughter that made headlines in the British press the next day: "I am a baby Aryan/not Jewish or sectarian/I never will marry an/ape or Rastafarian."

He has also claimed that Jews bring misfortune upon themselves by virtue of their race. "If I was a Jew, I would be far more concerned, not by the question of who pulled the trigger, but why; and I do not think that has ever been properly investigated," Irving once said. "There must be some reason why anti-Semitism keeps on breaking out like some kind of epidemic."

Still, Irving thinks he is winning this case, as his Web site makes clear. He hides nothing: He posts full transcripts of the trial (until the transcript company forbade him to do so Feb. 7), he posts links to every press clipping (regardless of how unfavorable it is to him) and he writes a "Radical's Diary," in which he shares his take on the day's proceedings.

The loser of this trial must pay its entire cost, which could mean financial ruin for Irving. But in some ways, he could win no matter how the sober-faced Judge Gray rules. Deborah Lipstadt refuses to debate Holocaust deniers because "it would elevate their anti-Semitic ideology to the level of responsible historiography," according to the first chapter of the book at the heart of this lawsuit.

But through his lawsuit, David Irving has entered the ring with the world's leading Holocaust historians. He has had his day in court.

Shares