Ursula K. Le Guin is one of the few writers I know who excels at both political fiction and epic fantasy. She's brilliant at both. But unfortunately, she's not always brilliant at both at the same time, and indeed, bringing them together is very, very hard. The intuitive demands of myth-making are only uneasily combined with the keen analysis required by a search for justice and equity.

As an avid Taoist, Le Guin knows this better than anyone. Suspect all correctives, look askance at attempts to restore benevolence and righteousness, Le Guin might say, yet her two new books, "Tales From Earthsea" and "The Other Wind," have been written as a sort of corrective to her stunningly inventive Earthsea Trilogy, originally published between 1968 and 1972.

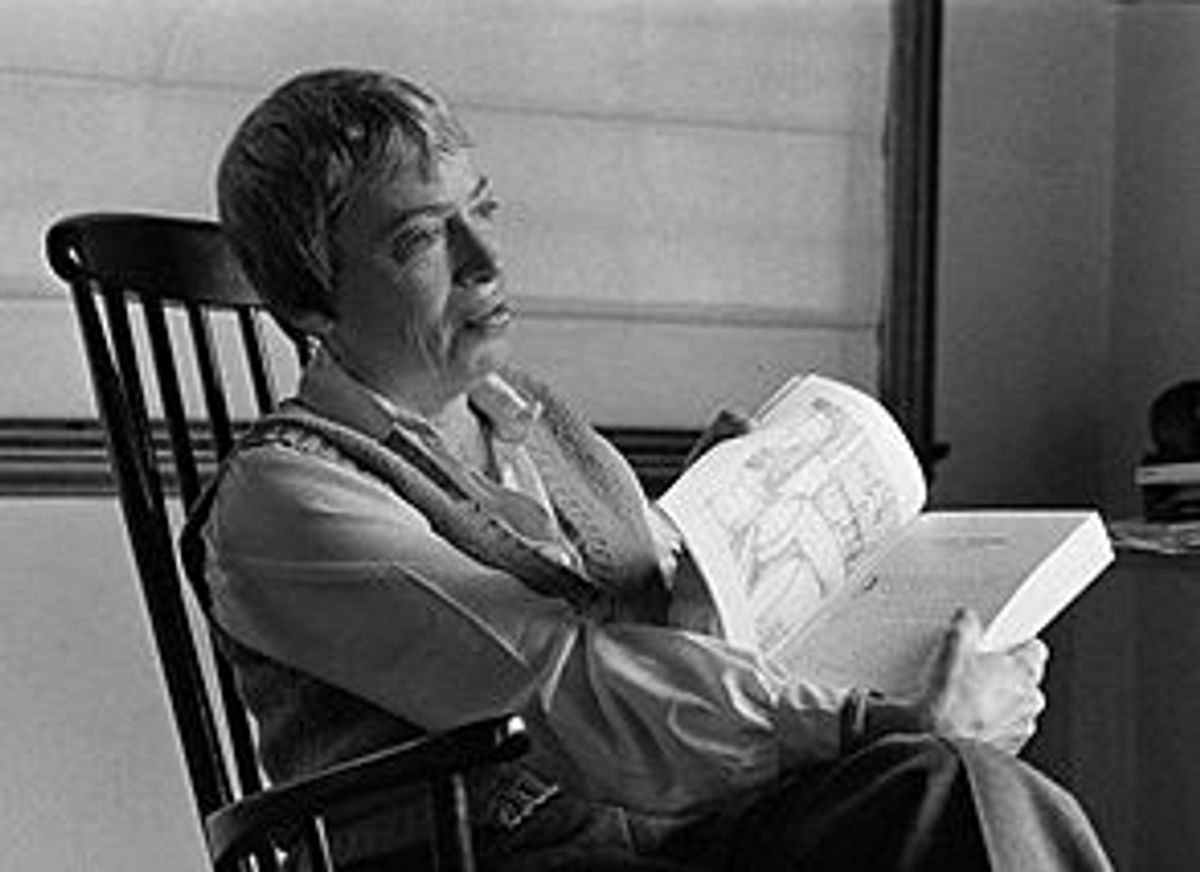

In the new story collection and novel, Le Guin drastically revises the politics of her archipelagan fantasy world, changing its outlook on gender, class and hierarchy. Can a fantasy world have an outlook?, you may ask. Certainly -- just ask yourself if the elves are good in Tolkien, and if his trilogy believes in kings. Le Guin, who is now 72, has also drastically revised Earthsea's worldview on death.

I loved the three original Earthsea books -- "A Wizard of Earthsea," "The Tombs of Atuan," and "The Farthest Shore" -- but the trilogy, like the "Tao Te Ching" itself, was a little quiescent about evil. In it, "keeping the balance" was always more important than fighting slavery or other human wrongs.

When wizards in the novels were smart, they did as little as possible and hung out in the woods. Action and power didn't avail much. Note: this was also one of the best things about the trilogy. Few writers of epic fantasy would have dared to have a work end with the hero "neither losing nor winning" or, as in "The Farthest Shore," with the same hero, Ged, completely losing his power.

Le Guin has always shown an openness to writing about loss, defeat and death, an openness that is extremely unusual (and refreshing) in the triumphalist world of fantasy. But fantasy is, on some level, always about triumph and especially the triumph over evil, and the trilogy's main strength also makes it unsatisfying and on a certain level ethically troubling. (Here's a corrective of my own: After Sept. 11, Le Guin's Taoist refusal of triumph makes much more sense to me. Fantasies of ultimate victory over evil now seem more troubling.)

Then there was the novels' attitude towards women. Though Le Guin is a feminist, her school for wizards, Roke, only admitted men, and women's magic in her world was both "weak" and "wicked." (The other deeply annoying thing was that Ged never became lovers with Tenar the Kargish girl who bravely renounces her position as a priestess of evil power, an act that's typical of the very boldest things women get to do in Earthsea.) With "Tehanu," a late addition to Earthsea published in 1990, and these two just-published books, Le Guin has taken care of all three problems. But fixing problems, as Le Guin would be the first to point out, is one of the most problematic things a writer can do.

"Tehanu" was awe-inspiring and infuriating at the same time because it introduced the notion of "a bad thing" (the burning, beating and rape of a child by her parents) into the pious, "good and evil are one" world of the Archipelago wizards. The abuse it detailed could not be looked at honestly in a way that could lead anyone to conclude that good and evil were one.

But in the process, the novel rather proved Le Guin's earlier point. "Tehanu" is feminist, fascinating and daringly self-critical, but it is also didactic as sin. Its two heroines -- Tenar, now adult and suddenly a housewife-Everywoman, and Tehanu, the abused little girl -- were one-dimensional and generic. They were more embodiments of Le Guin's politics than fully realized characters. Unlike Ged, they barely had shadows.

Eleven years later, Le Guin has come back to Earthsea again. This time she gets it righter. The story collection, "Tales From Earthsea," is bracing. "The Finder," the longest story, also tackles abuse, but embodies it much more successfully in myth. It is chilling and beautiful, a description of the slavery of a wizard -- and most other people in his world -- in the dark years before Roke was founded. Le Guin writes of 20-year-old Otter, forced to be a slave-wizard to a crazy mage named Gelluk who thinks mercury mining and the slow murder of his slaves through disease and starvation are the key to ultimate power and beauty. There are echoes of the Holocaust in Gelluk's exultation in his enslaved refiners' sores and diseased spittle, which he believes add to the mystical powers of the metal . He worships mercury as "the All-King." In the time Le Guin is writing about, wizards -- men and women both -- are nearly all forced to serve wealth and power.

Le Guin's descriptions of abuse in "The Finder" are so traumatic that they can almost not be read. Otter is constantly tortured with spells and beatings, and led around on a leash to do magic for Gelluk. A woman slave he meets, Anieb, is bald, naked, toothless and covered with sores -- that's what a 20 year-old looks like after only a year of labor as a mercury cooker.

Otter tries to find trust in the terrible place. There is immense beauty in the poems Le Guin makes up as nonsense scraps-nursery rhymes that are the record, hundreds of years later, of Otter's efforts to flee. (They are a record the way that Humpty-Dumpty is a record.) Those efforts depend directly on his cooperation with women -- some caring, rebellious women in particular, but also the entire gender at a time when women are the most oppressed people in his world -- to save themselves and him:

There was a wise man on our hill,

Who found his way to work his will.

He changed his shape, he changed his name,

But ever the other will be the same.

So runs the water away, away,

So runs the water away.

I'm not going to give away the ending, but Le Guin goes into the founding of Roke, which is accomplished -- surprise! -- mostly by women. Much of the collection (as well as the novel, "The Other Wind") details the subsequent history of Roke and how it came to ban women students and teachers. In the process we learn how "higher magery" itself came to be an art expected only of men, how the institution of Archmage was founded -- and how it is an institution much more like that of Archbishop or Pope than readers might have imagined.

Perhaps my favorite revelation is the one about sex, and why throughout the Earthsea trilogy all the wizards (even sexy Ged) didn't have it. We learn that the Archipelago wizards began putting spells on themselves and everybody else to keep the people around them from thinking about sex. This was after male mages decided wizardry should be purified of sexual energies and banned women from the school.

A nice story called "Darkrose and Diamond" is about wizard who falls in love even though he is supposed to be celibate, and also about the false idea that magic depends on cutting oneself off from all sorts of other powers -- sexual, creative, parental. Delightful, also, is the factoid, given in an appendix, that Erreth-Akbe and Maharion were "heart's brothers," which apparently means gay lovers. This would be roughly equivalent to C.S. Lewis's Oyarsa of Mars falling in love with his Oyarsa of Jupiter. A compelling final story, "Dragonfly," is about the first girl who tries to get into Roke after the ban.

Partly, this is all lovely. I have always been troubled by the sexism of Earthsea, and it especially hurt when I read the trilogy for the first time at 24. But partly, it's as though Tolkien had woken up 30 years later and written a new volume in which Gandalf's wizardry is revealed to be a fundamentally corrupt institution and Bilbo is discovered to have raped a few young hobbits.

I'm not sure beautiful stories should be "corrected," even when they are sexist, hierarchical and gross. It might possibly break a fundamental covenant between writer and reader for the author to "reveal" that her fantasy world was radically different, and far worse, than she had previously told us.

Thankfully, "The Other Wind" is not only about the sexism of Le Guin's earlier world. Well, sexism is a major subject, as is the original, painful division between dragons and humans, who used to be part of the same species (sort of like the traumatic division of the lovers' bodies in Plato's "Symposium"). The exiling of humans and dragons from one another entails the separation of wisdom from wildness, morality from freedom. It is a much smarter version of the Fall, or as the truncated surviving species both call it, Verdunan, the division.

But mostly, "The Other Wind" is about death. Death was a big, big subject in the original Earthsea books as well, but Le Guin approaches it much differently here. And here her emendations do not seem ham-handed, but instructive, deeply interesting and moving. Alder, "a common sorcerer," comes to visit Ged, who has long been without power. Alder has troubling dreams of the dead, especially his wife, who has kissed him across the "wall of stones" that Le Guin made so intensely real in the trilogy. (It is the wall that separates living and dead.)

But Alder loves his wife. He doesn't mind kissing her, only that she is apart from him -- and seems in pain, and begs him to "free her." In the trilogy, the dead lived in a "dry land" where the mother did not touch her baby and lovers passed each other in the streets. In the trilogy, this did not seem so horrible, but here it does -- as though death had come closer to Le Guin and through this novel, to the reader. A bit the way it felt closer to us in New York the other week.

Love, too, is much more central and important than in the other Earthsea books. The loss that all lovers face, even when they are completely constant and loving, is one of the aching subjects here. In the first few pages of the novel, Ged feels "a sadness at the very heart of things," and in fact essential loss, essential grief is the main thing that "The Other Wind" is about -- which makes me respect it immensely.

How to address that sadness is this novel's question. As the book opens, something is changing -- the dead didn't used to be able to touch the living, but now Alder's wife has touched and kissed him. Other dead people come to him in dreams and try to touch him, too. Also, something is happening with our cousins the dragons -- they're attacking the Archipelago en masse, when only a few of them used to attack before. And King Lebannen, still unmarried, has been sent an improbable, Middle Eastern-like, veiled bride from Kargad.

Tenar is the real hero here. She is elderly, and Ged is extremely elderly, and a great deal of the novel's drama lies in whether she will manage to save the world and get home to Ged before one of them passes away.

I love this. It's one of the most moving things Le Guin has written.

Death itself has changed in "The Other Wind "(as Alder has found out). Suddenly, the dead clamor to lose their names, to join with soil and rock, to meld with the world and to be reborn as something else, like the rest of creation. Those who remember the "Tombs of Atuan" will recall that the Kargish say that "the accursed-sorcerers," that is, the people of the Archipelago, do not get reborn, as the Kargish do -- they are damned eternally.

That is, they stay themselves forever, in "the dry land." This turns out to be connected to the fact that they have "true names," the essential foundation of the Archipelago's wizardry. The true sadness of wizardry as it has been practiced in Le Guin's world turns out to be that lovers cannot rejoin each other after death "in rocks, and stones, and trees. "

Le Guin, writing now, finds these separations a problem, and for that I applaud her.

Shares