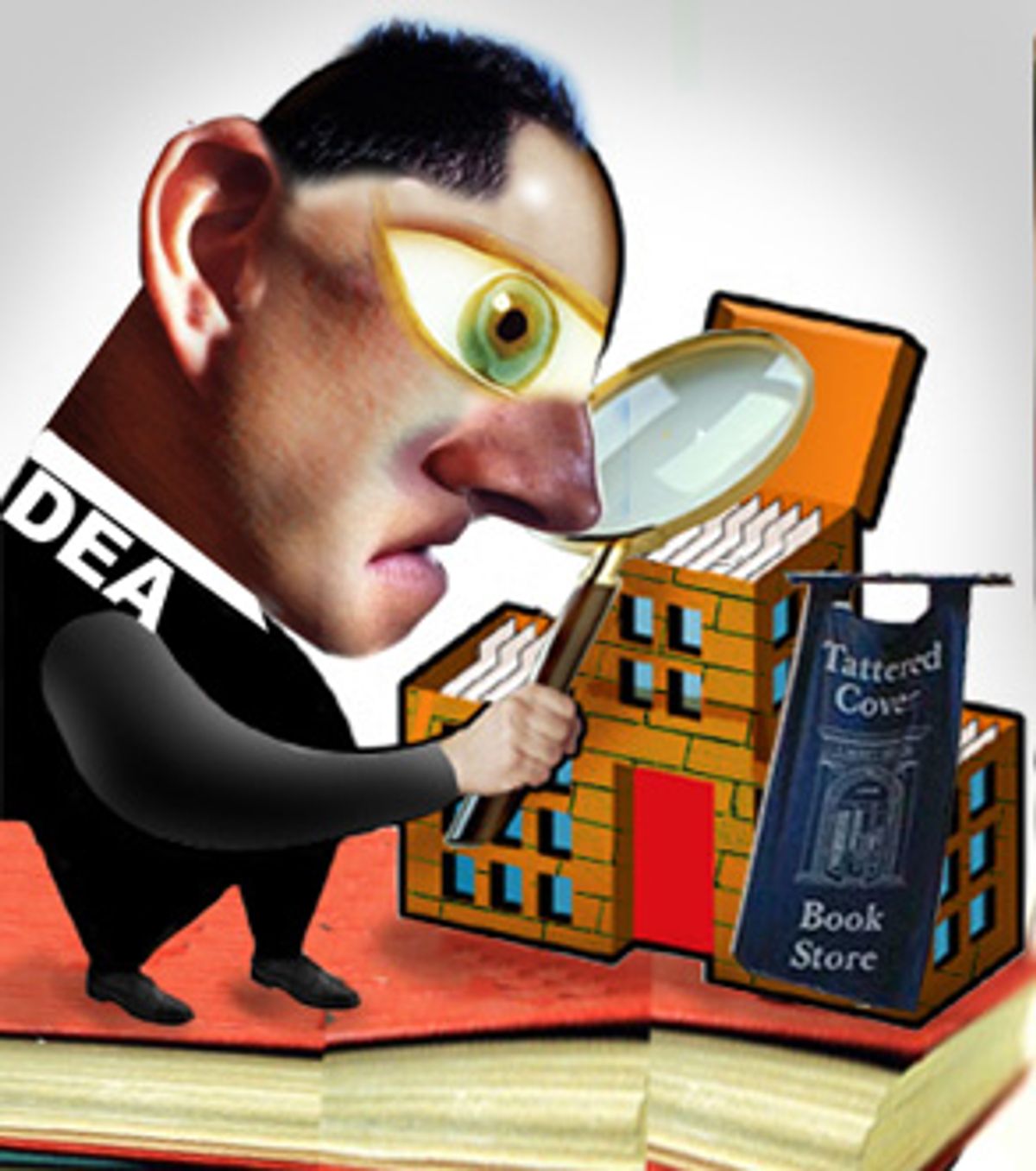

Joyce Meskis vividly remembers the day when five drug task force officers walked into her bookstore with a search warrant. "I was dumbstruck," she said. "Even though they were polite, it's a daunting experience."

One of the largest independent booksellers in the country, Tattered Cover has over 100,000 titles and a study-like atmosphere with plenty of what Meskis calls comfortable "grandma's attic" furniture. The brick, turn-of-the-century building seems an unlikely place for criminals, and the police probably thought that day's task would be quick and easy. But almost two years later, the warrant demanding that Tattered Cover hand over records of one of its customers' purchases remains unexecuted, held off by lawyers and temporary restraining orders.

Although many people aren't aware of it, in the eyes of the law buying a book is different from buying a bicycle or a pack of cigarettes. Through the years, the protections accorded materials covered by the First Amendment, such as books and newspapers, have evolved to protect the institutions that provide those materials as well. So when law enforcement officials say they just want information about the books a suspect purchased, booksellers and civil rights advocates see the demand as something that could erode book buyers' privacy and First Amendment rights.

"If we allow law enforcement access to customer records whenever they think it's convenient, customers won't feel secure purchasing books and magazines that are their constitutional right to buy," said Chris Finan, president of the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression. "It's important because many books are very private, or about sensitive issues, and if they feel booksellers turn over buying information at regular intervals, customers won't buy those books." By extension, this could have a chilling effect on the types of books that end up being published.

Tattered Cover's ordeal began in March 2000, when the Adams County District Attorney's Office contacted Meskis to inform her that the Drug Enforcement Agency was planning to subpoena the store for one of her customer's sales records. During a raid of a methamphetamine lab in a trailer park in suburban Denver, authorities had found an empty Tattered Cover shipping envelope addressed to one of the suspects in an outside trashcan, and two nearly new books, "Advanced Techniques of Clandestine Psychedelic and Amphetamine Manufacture," by Uncle Fester, and "The Construction and Operation of Clandestine Drug Laboratories," by Jack B. Nimble, inside the trailer. The DEA planned to strengthen its case by tying the suspect's illegal activities to his purchases of books outlining how to make methamphetamine.

Meskis answered that such a request was a violation of First Amendment rights and said she would fight it in court. "I thought that was the end," she recalled, "but it wasn't." Instead of bringing it to court, the DEA persuaded a judge to authorize a search warrant, which would be immediately executable and would bypass judicial interference. That's how the five task-force officers wound up in her bookstore.

Meskis' first try at quashing the warrant wasn't as successful as she'd hoped. In October 2000, a Denver district court judge narrowed the warrant's scope but ordered the store to turn over the information. She appealed that ruling to the Colorado Supreme Court, and on Dec. 5, 2001, lawyers from both sides presented oral arguments. The decision is expected sometime this spring.

The case has attracted nationwide media attention and the support of dozens of civil liberties groups and a phalanx of writers. On Jan. 11, at San Francisco's A Clean Well-Lighted Place for Books bookstore, over 500 people attended a benefit to help defray legal costs that have arisen from the case. Daniel Handler, author of the Lemony Snicket series, helped organize the event, attended by other literary luminaries such as Pulitzer prizewinner Michael Chabon, McSweeney's editor Dave Eggers and novelist Dorothy Allison. "It's startling and disappointing to me," Handler said about the case. "There are so few countries where you can't get in trouble for what you read, and the U.S. appears to be falling from that short list."

In fact, according to Finan, less-publicized demands by law enforcement for customer information have become "alarmingly" more frequent over the past two years. And not only independent booksellers, but giants like Borders and Amazon, have been subpoenaed. In perhaps the most egregious case, authorities ordered Amazon to give them a list of all customers in a large part of Ohio who had ordered two sexually oriented CDs. Independent booksellers have been especially hard-hit by these cases. And fighting them without the benefit of a corporate budget or in-house counsel means hefty legal bills and months, if not years, of hassle.

"It's a big problem," said attorney Theresa A. Chmara of Jenner & Block in Washington, DC, who is on the ABFFE board and wrote an amicus brief for Tattered Cover. "This is an opportunity for a state supreme court to determine how these cases should be done and explicitly define how they should be handled."

Meskis, Finan and other advocates contend that bookstores need the same protection of their patrons' rights that suppliers of other types of First Amendment materials enjoy. For example, in 1987, after a Washington weekly newspaper published a list of videos rented by Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, Congress passed the Video Privacy Protection Act, which severely limits the information video stores may release about their customers. Public and private libraries have for decades butted heads with groups and individuals attempting to gain access to their lending records, and there are now statutes in 48 states that restrict the ability of librarians to give out such information.

Even if law enforcement officials believe they urgently need the information, it's much harder for them to get First Amendment materials than to get credit-card receipts or phone records. The court applies a higher standard to warrants or subpoenas for such materials. It requires demonstration of compelling need for the information and direct relevance to the investigation; the requests must be limited in scope, and are to be made only after all other investigative outlets have been exhausted.

The problem bookstores face is that there is little precedent regarding law enforcement's right to search their records.

In 1998, Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr made the first attempt -- at least, the first attempt that free speech activists know of -- to get customer sales records from a bookstore. It came pursuant to Starr's investigation of Monica Lewinsky's affair with former President Bill Clinton. He subpoenaed two Washington area bookstores for information about her purchases. One store, Kramerbooks, was especially adamant when they refused the request, and the case went to court. Chief U.S. District Judge Norma Holloway Johnson refused to quash the subpoena but stated that the bookstore had successfully shown that the subpoena had a potential chilling effect on First Amendment rights. She ruled that the government must prove "a compelling need for the materials it seeks and whether there is a sufficient connection between that information and the grand jury's investigation." Kramerbooks planned to fight that decision, but the case was resolved when Lewinsky agreed to provide the records voluntarily.

"There's so little precedent, given the fact that bookstores didn't have to worry about these requests until the Lewinsky case," said Judith Krug, director of the office for intellectual freedom for the American Library Association. "But that opened the floodgates."

Since then, four other cases, including Tattered Cover's, have come up, and in each one the bookstore chose to fight. According to Finan, "Many of the requests have been outright fishing expeditions. They haven't been respectful of privacy rights or the First Amendment.

"We're not asserting a categorical First Amendment for all records," Finan explained. "But in many cases, police don't do everything they should have done. They left avenues uninvestigated and went to the bookstore because it's more convenient for them. They should never have access until they have done everything they can. They need to respect bookstores for what they are: purveyors of ideas, not a hardware store."

What the district attorney's office didn't realize when they messed with Meskis was that she was probably the last person in the country with whom they wanted to pick this type of fight. She is a former president of the American Booksellers Association and chair of the task force that established ABFFE. She is also one of the coauthors of the group's pamphlet "Protecting Customer Privacy in Bookstores," and is a veteran of several Colorado First Amendment challenges.

Meskis' attorney, Daniel Recht, called the Denver D.A.'s office and was granted an unusual one-week extension before the search warrant was carried out, which enabled them to get a temporary restraining order and bring the case to court.

Attorney Andrew Nathan, of Nathan, Bremer, Dumm & Myers, gave oral arguments to the Colorado State Supreme Court on behalf of law enforcement and said that the suspect's book purchases are an essential piece of evidence and that authorities are merely trying to obtain information during the investigation of a crime. "It's a business record, a single business record," he said. "We're not exploring the reading habits of the suspect. We're not asking [them] to tell us everyone they sold the book to. The warrant only seeks to know if the suspect bought books about manufacturing of methamphetamine at meth labs."

Recht contends that the customer sales records have limited relevance to the investigation and that there is no compelling need for law enforcement to bypass First Amendment protections.

"It's not an issue of getting bad guys and having a bunch of intellectuals getting in the way of doing that job," Recht said. "This is a very important issue. Book readers need to be confident that the government will not know what they buy and read. That's inherent in the freedom of expression. There's no absolute privilege, but you can't let law enforcement trample over the First Amendment."

Like Krug, Recht blames Starr's initial attempt for the subsequent subpoenas. "After Starr attempted to subpoena for the records, law enforcement saw that they can attempt to get this information. And they've tried ever since."

But while law enforcement might be able to construe a plausible argument for trying to get the Tattered Cover information, other cases since the Lewinsky subpoena have had less legal strength. In fact, in some instances, law enforcement agencies have asked for the information when they clearly should have never sought it in the first place.

Of the three other cases, two involved giant corporate booksellers that were savvy about the law and had the financial resources to combat the request. In the summer of 2000, a Borders store in suburban Johnson County, Kan., near Kansas City, was subpoenaed for information regarding a sealed indictment in a drug case. When the company's lawyers fought the subpoena, a federal judge quashed it.

A more recent case evolved out of the investigation of New Jersey Democratic Sen. Robert Torricelli. The FBI subpoenaed a number of bookstores around the country for cash purchases made by Torricelli and seven other people as far back as 1995. "They ran roughshod, and colored outside the lines on this one," said Phil Bevis, owner of one of the subpoenaed stores, Arundel Books in Seattle and Los Angeles. "The Justice Department drafts these ridiculous subpoenas and warrants that are not even in accord with their own standards, let alone the law."

Bevis said that when the FBI agent arrived and started interrogating his staff, it was intimidating and served as a "gut check," but that even if he ended up losing the case or going to jail, he knew what decision he would make. "At the end of the day, I know that I decided that if we were required to report reading habits to the government, I'm out. Once you reach that decision, you're not going to do it on any level."

Bevis said he was surprised that law enforcement would place such importance on someone's book purchases, since in many cases the information would be difficult to interpret or would be misleading. For example, if a banker buys a book on money laundering or a FBI agent buys something about terrorism, it's likely that he is researching matters related to his profession, not planning those activities.

"You think about the information we have about people, but without context, its just information," he said. "They see this as any chance to make a case, but they're not looking five moves ahead. They don't want this information to be public, either. Nobody wants the information we have to be communicated to employers or to the government. Nobody wants to edit what they think, or the books they buy. I've never had anyone say they're not interested in their privacy, but thousands have said the exact opposite."

Although the Justice Department eventually dropped the requests when it found out that Bevis and other storeowners would fight the subpoenas, it wasn't a total victory. "It's going to take us years to pay off the attorney bills," he said. "The whole thing was expensive and time consuming and it's not my job to get the Justice Department to do their job. I've lost a lot of respect for my government over this. It's a disgrace."

Perhaps the most wide-ranging request for customer information of this kind came in the summer of 2000, when Ohio authorities subpoenaed Amazon.com. They requested records of all the people in a large part of Ohio who had purchased the "Cyborgasm I" and "Cyborgasm II" audio CDs, trying to identify a stalking suspect who had sent the CDs to his victims.

Amazon attorney David Zapolsky says the company told Ohio authorities that Amazon would not answer an out-of-state subpoena and that it wasn't the company's policy to give out that information. "We always raise the First Amendment issue when we're confronted with a request for buying habits or reading material, because it's a serious request," he said.

But Ohio authorities were persistent. They asked the Seattle district attorney to issue a search warrant for the information. Then Amazon officials found out something that Ohio authorities hadn't told them: Although the case was still technically open, the primary suspect that Ohio was hoping to match to the purchases -- local TV personality Joel Rose -- had committed suicide a few weeks earlier. Ohio authorities had suspected that Rose was the stalker. After police took DNA samples from Rose and the story broke in the news, Rose wrote notes to his family and public officials denying his involvement, and then shot himself in the woods behind his house. Ohio authorities were apparently hoping the Amazon sales records would clear them of the perception that they pushed an innocent man to suicide. Ultimately, the Seattle D.A.'s office refused to issue the search warrant. As it turned out, Rose's DNA did not match the DNA found on some of the stalker's mailings.

While these cases represent failures by law enforcement to procure records, there may have been unpublicized cases where authorities were successful.

"Most bookstores don't have the financial wherewithal or the desire to fight these types of requests," Recht explained. "Also, they may be unaware of the First Amendment issues and just turn over the information." He added that most of these cases were likely to go unreported, for booksellers would not want to publicize that they were ignorant of the law or that they would give out their customers' records. A favorable decision by the Colorado Supreme Court in the Tattered Cover case, he says, would "show bookstores around the country that they do not have to and should not honor these subpoenas and that they need to protect First Amendment rights."

Recht said that if the decision goes against Tattered Cover, the only place to appeal is the U.S. Supreme Court, though he considers that a "remote possibility."

"I'm cautiously optimistic," he said. "I think the oral arguments went well, but that doesn't necessarily mean that's the case." He also stated that the Colorado Supreme Court has a record of deciding such cases on the side of civil liberties.

But however Colorado decides the case, the conflict between booksellers and law enforcement is far from over. In fact, although a decision for Tattered Cover would give attorneys a precedent, it wouldn't give bookstores the type of protection that libraries and video stores enjoy. In fact, courts in different states could decide differently on almost identical cases. Until there are laws similar to those protecting other types of First Amendment materials, cases between booksellers and law enforcement are likely to continue to be heard by courts around the country.

Finan hopes that the decision will at least halt the most egregious attempts to search bookstores' records. "If we don't fight this, then we'll see more and more cases that look like the Amazon case," he said. "Right now there is no protection and that's what we're trying to argue in court."

At Tattered Cover, Meskis said that if the decision goes against her, she plans to keep fighting against giving up the records. "That would be my inclination," she said. "We'd want to see it through to the end." But she said she hopes that it doesn't come to that.

"If these types of requests are allowed, there will be a distinct chilling effect felt as to the freedom of expression; otherwise I wouldn't be doing this," she said. "The debate within our government system as to right and wrong would be silenced, and that does not make for a healthy society."

Shares