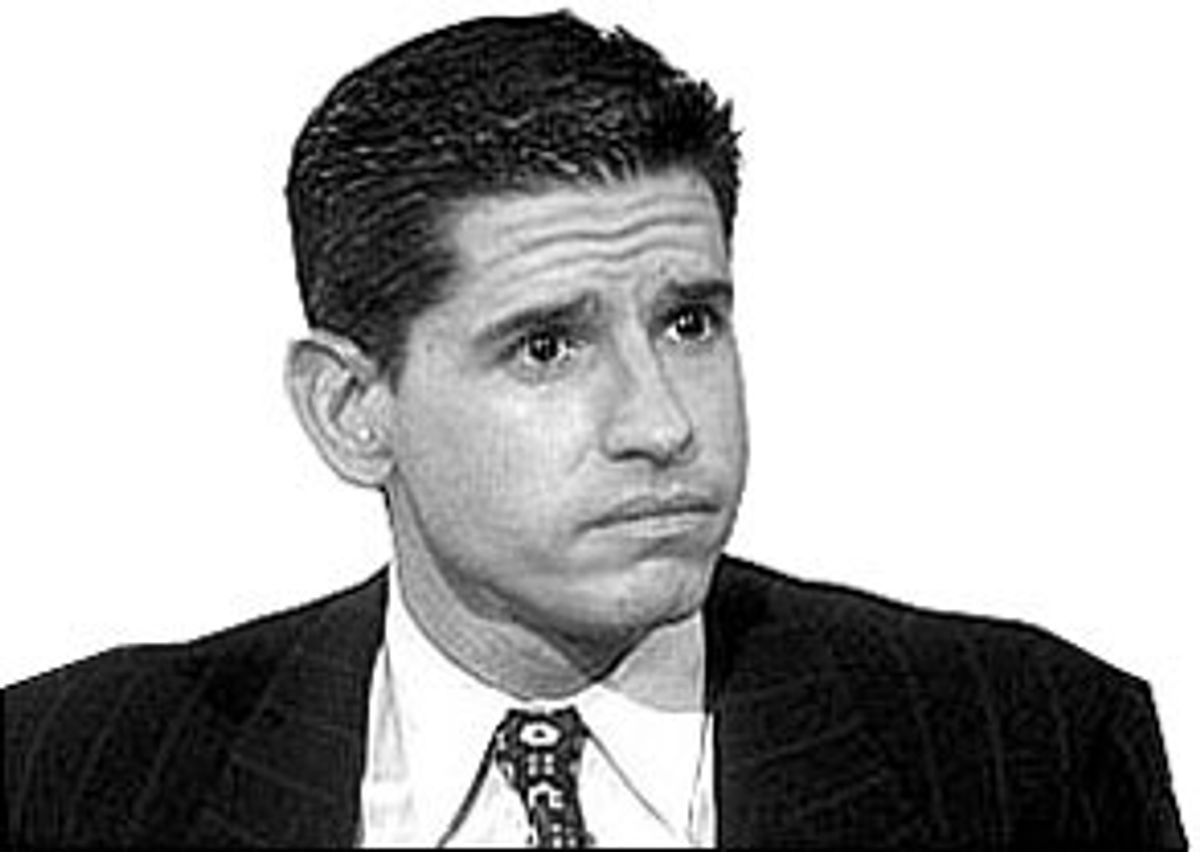

Conservative writer David Brock received nearly $40,000 from the American Spectator's Arkansas Project, project records show, despite claims by Spectator editors that Brock had nothing to do with the controversial Clinton-bashing project.

Brock moved to the center of the drama over President Bush's solicitor general nominee, Ted Olson, when he told a Judiciary Committee staffer and the Washington Post that Olson was integral to the Arkansas Project -- the American Spectator's aggressive investigations into the private life of President Clinton, funded with roughly $2 million from conservative billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife -- despite Olson's claims to the contrary. Olson's supporters struck back, insisting Brock had nothing to do with the project.

"Although Mr. Brock has lately claimed to have been part of the so-called Arkansas Project, he was not," Spectator editor in chief R. Emmett Tyrrell and executive editor Wladyslaw Pleszczynski wrote to Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah. "The record on this is indisputable."

But according to an internal expense analysis of the Arkansas Project prepared on Sept. 1, 1995, obtained during a 1998 Salon investigation of the American Spectator, Brock received thousands of dollars in reimbursements for travel, conferences, telephone calls, office supplies, postage and books and periodicals from the Arkansas Project. The documents, titled "Expense Analysis - Arkansas Project," are for the fiscal year ending in June 1995. According to the documents, close to $40,000 worth of Arkansas Project funds appear to have been used to reimburse Brock for work expenses.

Contacted Wednesday, Brock further disputes Tyrrell's allegations. "The truth is, I was a part of the Arkansas Project and I've always said that I was," Brock told Salon. "What they're trying to say now is that I never had anything to do with the Arkansas Project because they're saying that I'm now retroactively trying to link myself to the project in order to damage Ted Olson.

"I was part of the Arkansas Project, and they're lying about that. It's a baldfaced lie," Brock said. Tyrrell did not return phone calls by Salon Wednesday for comment.

A short time later, Brock faxed his own letter to Hatch, writing that "Tyrrell's assertion is false. During the years 1994 and 1995 I took several trips to Arkansas to research Arkansas Project matters." Brock also said he was faxing to Hatch his own copies of Spectator expense records showing his involvement in the project.

In their letter to Hatch, Tyrrell and Pleszczynski also state that Brock's "well-known 'Troopergate' story originated and was completed before any such project existed." However, according to the accounting records, travel expense reimbursements for Brock date back as far as five months prior to the December 1993 publication of his "Troopergate" article -- and they were recorded as Arkansas Project expenses.

Though Brock was unable to recall specific trips he took during the summer and fall of 1993, he says he does recall two Arkansas Project-related trips he took in 1994, including one trip with Tyrrell to Miami, where he met with an Arkansas Project investigator to discuss whether White House attorney Vincent Foster's death was actually a murder.

Brock also says he recalls a trip to Hot Springs, Ark., to meet with Parker Dozhier, a fishing resort proprietor who was working for the Arkansas Project and, according to Spectator records reported in previous Salon investigations, was paid $48,000 by the magazine for his services. In 1998, Salon reported allegations by Dozhier's live-in girlfriend, Caryn Mann, and her son, Joshua Rand, that Dozhier made numerous cash payments to David Hale while Hale, a disgraced former judge central to the Whitewater investigation of President Clinton, cooperated with the Kenneth Starr investigation.

Hale, meanwhile, was represented in his attempt to quash a subpoena for Senate Whitewater testimony by Olson. And reports of the payments to Hale sparked an investigation of Starr's investigation by Michael Shaheen at the Justice Department -- and raised serious conflict-of-interest questions for Starr, a longtime Olson friend who had been planning to become dean of the Scaife-endowed Pepperdine University School of Public Policy. (He subsequently withdrew himself from the job.) Shaheen's investigation remains under seal.

Sen. Patrick Leahy, the ranking Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, has requested the Shaheen Report from both the Department of Justice and the Office of Independent Counsel, but his requests have been denied. He has also been unable to obtain Arkansas Project records from the American Spectator. On Saturday, Leahy called on Hatch to join him in a bipartisan probe into the confusion surrounding Olson's role in the project.

In his response to Leahy on Tuesday, Hatch argued that the conclusions of the Shaheen report corroborate Olson's testimony. In his letter, Hatch writes, "I am concerned that ... the definition of the 'Arkansas Project' appears to have blurred to mean anything related to criticism of President Clinton that appeared in the American Spectator. Such a definition is unworkable."

But the most serious charges leveled in regard to the Arkansas Project were over the alleged payments to Hale, and they raised questions about whether the American Spectator violated nonprofit tax laws by conducting partisan opposition research. Executives at the American Spectator Educational Foundation were concerned about such violations, and prepared for an audit of Tyrrell's use of Spectator funds. Documents show that Tyrrell's $598,000 home in McLean, Va., was owned by the nonprofit foundation that publishes the magazine, and that his lavish lifestyle was augmented by a generous salary that reached $318,000 a year.

According to Hatch's letter to Leahy, the investigation into the Hale charges, led by Shaheen, found no substance to the allegations. "At the conclusion of their review, they issued a statement on July 27, 1999, in which they concurred with the conclusions of the Shaheen Report that no prosecutions were warranted and that 'many of the allegations, suggestions and insinuations regarding the tendering and receipt of things of value were shown to be unsubstantiated or, in some cases, untrue.'"

Hatch also disputes Leahy's assertion that he was denied access to the report by the Justice Department and the Office of Independent Counsel. "I believe you are mistaken. On May 2, 2001, the Office of Independent Counsel came to the Judiciary Committee offices and made available all relevant non-grand jury material from the Shaheen Report for review by you and I and one designated staff member each." In his reply to Leahy, Olson echoed Hatch. The Shaheen Report "apparently concluded that the allegations that had prompted the investigation were unsubstantiated, exaggerated or altogether false." But then he offered something more interesting, noting, "I had not seen the report until last week when heavily redacted portions of it were made available to me after those same portions, with lesser redactions, had been made available to Senator Leahy and/or his staff."

And that's the problem. In their 1999 public statement about the Shaheen Report, retired federal Judges Arlin Adams and Charles Renfrew issued extraordinarily vague language about the findings: "Many of the allegations," they said, were "unsubstantiated or, in some cases, untrue." However, without access to the report in its entirety, the context of the allegations and the investigation remains unclear, and heavily redacted copies probably would prove even less illuminating.

And sources, including former Spectator employees, have questioned the magazine's use of funds in conducting the Arkansas Project. "This wasn't a legitimate use of tax-exempt moneys," a former Spectator employee told Salon in 1998. "I would suggest that what was going on here was opposition research, which would be fine if the American Spectator were a private business. But it is a tax-exempt 501(c)3."

Brock has similarly claimed that the Arkansas Project operatives were engaged in partisan opposition research rather than journalism. In the Post interview, Brock described how he had sought out advice from Olson on the Arkansas Project-commissioned story about the death of former White House attorney Vince Foster. Brock believed the piece to be unsubstantiated and tried to get Olson to intervene on his behalf with Spectator editor in chief Tyrrell. Brock told the Post that Olson told him that "while he didn't place any stock in the piece, it was worth publishing because the role of the Spectator was to write Clinton scandal stories in hopes of 'shaking scandals loose.'" If true, the accusation suggests that the magazine was engaged in partisan dirty tricks that could be seen as illegal under tax rules for 501(c)3 organizations.

However, Olson denies the allegation in his letter to Hatch. "As I told Mr. Brock at the time," Olson wrote, "the article did not appear to be libelous or to raise any legal issues that would preclude its publication. I made it plain to Mr. Brock that I was not the magazine's editor, and did not intend to start telling the Editor-in-Chief of nearly three decades what should appear in the magazine.

"Mr. Brock felt that the article was too controversial or speculative, and I responded that the style and tone of a magazine such as this was not a matter for the expertise of lawyers, and that I was not in a position to help him," Olson wrote.

In his letter to Leahy, Hatch also criticized the role Brock's allegations have played in the confirmation process. In the May 15 letter, Hatch complained that he had learned about Brock's involvement with the committee through a report in the Washington Post, and said that he understood that Brock "had contacted the 'Judiciary Committee.'" Brock, however, says he never initiated contact with anyone on the committee regarding Olson's confirmation process. "I was contacted by a Democratic staffer who read me sections of Olson's testimony dealing with the Arkansas Project and asked me for my thoughts about his testimony and whether I had any information on these matters.

"If Hatch's staff had contacted me and if they want to contact me now, I'm perfectly happy to talk to them," Brock says.

Brock's allegations have thrown into further confusion Olson's already muddled statements about his involvement in the project.

Olson's responses have evolved considerably since he first sat before the Judiciary Committee on April 19. At the time, he told the senators that he "became aware of allegations regarding what came to be labeled the 'Arkansas Project' during my tenure on the Foundation's Board of Directors, in 1998, I believe." In a written response to questions dated April 25, Olson changed his story, stating, "I do recall meetings, which I now realize must have been in the summer of 1997 in my office regarding allegations regarding what became know as the 'Arkansas Project.'"

Then, in his May 9 response to the committee, Olson said it was not just as a board member, but also "in connection with my service to the Foundation as a lawyer," and that he "cannot recall precisely" when in 1997 he learned of the project. Curiously, in a May 14 letter to Hatch, Olson then backtracks, and says that he learned of the project "in my capacity as a member of the American Spectator Educational Foundation Board of Directors."

For Olson's advocates, meanwhile, Brock could not be a more upsetting obstacle. According to Spectator records, he was paid a whopping $195,000 salary in 1994 -- a large sum but not out of line with his status as the far right's most celebrated investigative journalist. In addition to "Troopergate," he gained fame for his "exposé" of Anita Hill, the law professor who accused Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment during his 1991 confirmation hearing. In one memorable phrase, he termed Hill "a bit nutty and a bit slutty."

Brock chronicled his own fall from conservative grace in a July 1997 article in Esquire magazine titled "Confessions of a Right-Wing Hit Man." He described how his career seemed to hit its apex when he published his famous "Troopergate" story in the Spectator. "Perhaps the most humiliating portrait of a sitting president and his wife ever published," Brock wrote, "the piece detailed graphically Clinton's history of extramarital affairs and exposed the culture of petty corruption, deceit, and cover-up that this behavior engendered."

But that all changed, Brock wrote, after "The Seduction of Hillary Rodham Clinton," his 1996 book on the first lady, which "not only failed to deliver the deathblow to the Clintons that everyone had expected but was in some respects sympathetic to its subject." Suddenly, he wrote, he was frozen out of the cozy conservative Washington circles he'd starred in, and he largely blamed Ted Olson and his lawyer wife, Barbara. He recounted a Whartonesque voicemail message left on his phone from Barbara Olson, disinviting him to a party after the Hillary book came out. "Given what's happened, I don't think you'd be comfortable at the party," she said.

Ever since, Brock has seemed to be on a tear against his former social scene, detailing in Esquire how former Rep. Michael Huffington -- once the great conservative hope in California -- had to come to grips with his homosexuality. Now some on the right are cowering in anticipation of his upcoming memoir, "Blinded by the Right: The Conscience of an Ex-Conservative," which will reportedly take aim at many high-profile conservative politicians, pundits and journalists.

Right-wing commentators are lined up to take their shots. Online, Lucianne.com maven Lucianne Goldberg, the literary doyenne at the center of the Monica Lewinsky affair, posted an alert: The "Turncoat Twinkie [Brock is gay] Attempts a Takedown," and warned him against "playing Chatty Cathy to the Senate Judiciary Committee," taunting: "David, darling, stop making a mess ... don't you know there are pictures out there?"

Wednesday, the National Review and the Wall Street Journal's online Opinion Journal took whacks at Brock. And the Drudge Report promised details from Brock's "explosive manuscript for the upcoming tell-all book" -- though the tidbits Drudge revealed were surprisingly tepid.

Still, the right can't explain away what the American Spectator's own records show: Brock's journalistic travels were financed by Arkansas Project funds, and clearly he knows more about the project than Olson's defenders would have the Senate Judiciary Committee believe. And by prevaricating about Brock, Olson and his defenders raise more questions as to what else they're not telling the truth about.

Shares